by Anton Rush

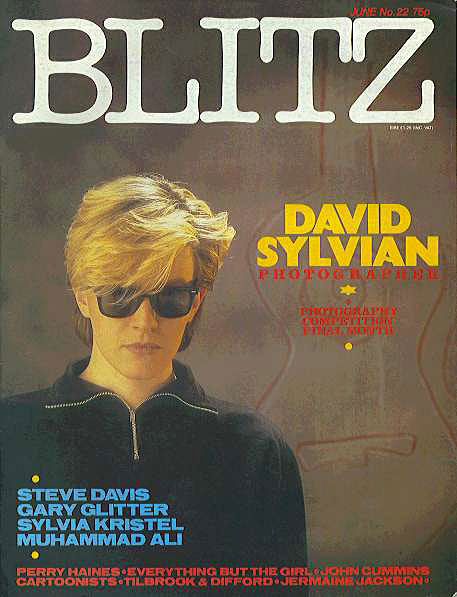

Gentlemen prefer Polaroids by Anton Rush (Blitz, June. 1984)

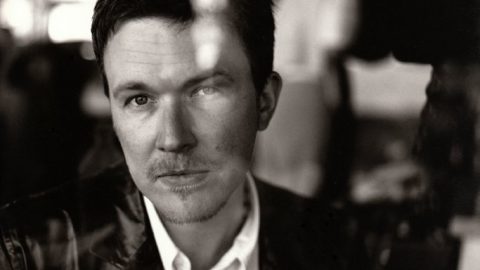

BLEACHED blonde hair, a hint of eye liner, expensive monogrammed socks, beaten-up white shoes that have graced a dozen fashion spreads, strong untipped caporal cigarettes, a stunning smile that causes make-up girls to turn to jelly, and more than a touch of zen in the way that he approaches everything. This is the kid from Catford, Dave Batt, or David Sylvian, who has an interest, slightly flirtatious, in Buddhism, who spends a great deal of the spoils of a successful career in music on being alone, and escaping the fans that have made him a household name. A man just turned twenty-six who has a desire to be an ‘artist’ in the mould of his hero Cocteau… “who was well-known for doing a lot of things equally as well as each other.”

I’ve done everything that I can to forget my childhood,’ says David with the expression of a middle-aged lady who’s just seen something nasty in a shop window. “I started writing songs when I was thirteen, just rubbish, it was all part of a world I’d created for myself, I never thought of doing anything else but music to be honest.”

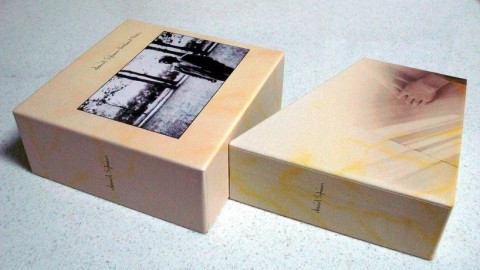

Now, with the encouragement of his Japanese girlfriend, he is exploring new avenues of his talent at the beginning of a solo career. There are photographs and drawings, an exhibition and a self-produced book, and a new album called Brilliant Trees, all of which separate him both financially and artistically from the image and style of Japan, of which he was growing increasingly tired.

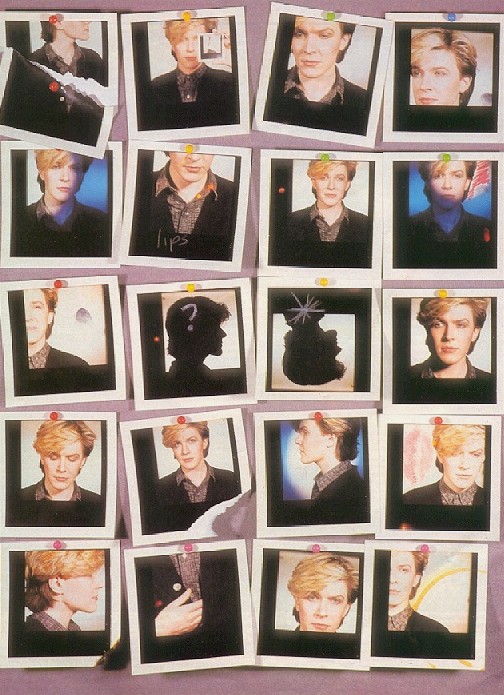

David Sylvian’s polaroid photographs date from 1982, and are only now seeing the light of day in the wake of David Hackney’s huge exhibition at the Hayward gallery in London last year. ‘The first impression of the photos is that they are Hockney. When I took them to some magazines to print they’d just say, no thanks, that’s too much like Hocknev.

“I find it all very narrow-minded. I mean, if you’ve got any credibility is an art critic you should be able to see the difference straight away. You should ask the question, has it got any credibility of its own ?”

The difference is not immediately obvious, and so without any credibility as an art critic I felt safe enough to enquire what exactly the difference is. “It’s not in the material but in the results. Hockney’s photos are about movement mine are more static,’ says David, happy that he’s lit the nail right on the head. “Anyway, people come up with similar ideas at the same time. One person dldnt create Cubism, it was created by a group of people, but everybody now associates it with Picasso. The times inspired people to come up with the same ideas as him.”

But why take polaroids at all?” It appeals to me because it’s so fast, it’s all there in five minutes. I never had any real cameras, I mean I had those idiot-proof ones, but I never got the film developed. I’m very lazy like that.”

The first polaroids that David took, not surprisingly, have a strong connection with solitude: “On the last Japan tour, I was spending so much time alone in hotel rooms. I enjoy being undisturbed, I enjoy the solitude, and I started doing self-portraits, and peeling things apart, and scratching the surface of the photo. I know that was done before I started doing it, but I hadn’t seen it, so everything I did was self-discovery for me.”

EVEN THOUGH the influential Hamilton’s Gallery eagerly accepted David’s photographs on their own merit, he feels that as a pop star he can never be sure of a true critical response to his work. “I’m very aware of the fact that most people might be interested in the things that I’m doing because of who I am. I mean, if this exhibition did very well it could be put down to the fact that I’m popular as a musician.”

There seems to be no way out of the trap, unless the photographs were exhibited under a false name. At the beginning of a promising career as a photographer, David’s past life hangs around his neck like an albatross: “I was very aware of the pop star thing. I mean, any pop star could have an exhibition of anything, it’s too easy. The galleries know that they’ll get people in, and that’s all they’re worried about really. Unless it’s a really good gallery, and then they have their reputation to worry about.

“I think that’s what put a lot of people off. They wouldn’t show the pictures because a pop star is not an artist. And that’s my impression too, in general I think that pop stars are not artists. Most musicians don’t have any creative talent. There are a lot of people who are in the business just for the money they can make, and those people epitomise what I don’t like about it, they’re as bad as the guys that sit behind the desks at the record companies.”

Of course, it doesn’t take a genius to guess the identity of the majority of people that will visit Hamilton’s to see David’s photos I think that it’s inevitable that there will be a lot of Japan fans visiting the exhibition and in a way that’s a compliment. Hopefully the people that like the music will also think that I might do something interesting in photography. But there won’t be any true critical response until the exhibition travels a little to places where I’m not known, like America and Europe. That’s really my ambition for it. All I want is that the pictures will get acclaim for themselves.”

There are no particular names in the world of photography that have influenced David, but he does have a favourite book: “It’s called Artists Of My Life, by Brassai, I love that book. Atmosphere is extremely important to me in photos, and that’s what Brassai has. I also like Angus McBean very much because there’s so much of his character in the pictures he takes.”

To make assumptions about the character of a photographer from the style of their work can be a dangerous thing, and a truly worthless exercise, but in the work of David Sylvian all the apparent threads of his character seem to come together; there’s a distance, a coldness, a detachment from the subject, and that disturbing stillness in all the pictures that seems to parody old Japanese prints, where it appears that the characters have been quick frozen. There’s also a balance that has a lot in common with his approach to music.

“There’s something that makes me choose to make a repetitive piece of music last for eight minutes and then to say that’s enough, it stops here. And with the photos it’s the same thing again, putting the polaroids together and balancing up the lines between them that don’t quite match, or taking a picture of this room here and deciding that all I want in it is you and not the rest of the room. It’s all my balance that dictates how that’s going to look, as well as it dictates a piece of music.”

I’M SUPPOSED to hate everything,” says David, laughing at my remark about his dislike of being interviewed, having his photograph taken, and reading spurious stories about himself in the dailies. “The interviews that I hate are the moronic ones:’ he flashes that smile again, which often seems to be a warning that he’d like to change the subject.

“I’m not an ordinary bloke, I could make no claims to be ordinary.” Again the smile comes as he tries to explain that he feels that success and stardom were almost pre-ordained for him since those early days working away on his songs in his bedroom after school.

David’s lifestyle is bizarre. He has two flats, one known to fans and one that is just beginning to lose its anonymity. Now he’s in the process of buying a house -the location, of course, is a deadly secret. Every two or three months he changes his telephone number, and even the record company can’t telephone him when they need to. When he tours he is surrounded by security, and spends his evenings alone in his hotel room. But despite being in a position that must be similar to finding yourself surrounded by cannibals who all want their own little bit of David Sylvian, he feels that his situation has made him a very privileged man, with a carefully created and well-protected space in which he can work, travel, and eat junk food as much as he wants to.

However there are still some irritations: “I get aggravated by finding girls outside the flat. I can understand why they are there, but I still can’t accept it. There are always one or two who hang on and want to feel that they are familiar with me because they know my address, or they’ve found out my telephone number, and they ring up all the time. That I find obnoxious. I just can’t stand it, sitting outside my door day after day, telephone calls day after day. It’s a lot of bother so I have to have people around me to deal with it.

“I also detest people making up stories about me, like the near fatal car crash which I survived by having plastic surgery! It’s very confusing at times. I mean, a lot of stars have an image that they take off, and that person doesn’t exist, other than in the newspaper. When they go home they live their normal lives, but I am what I represent to people. When I see somebody represent me in away that I can’t relate to, I think, I don’t want to be this person that they’re talking about. It feels like a very personal attack on me.”

David’s greatest fear has always been complacency. “I always thought that it was inevitable with too much success,” he offers, but now, working alone, he has had to start all over again and he finds the experience stimulating: “I was losing that feeling of a challenge with Japan, being so successful taht is was all beginning to become too easy. I feel the challenge again now that I’m on my own. I’m insecure enough to have to keep justifying my existence.”

(photography by Jill Furmanovsky)