by Tony Fletcher

Introduction by GEOFFREY ARMES.

There’s very few I’ve wanted to meet. A handful. To be honest, I don’t necessarily find pop stars all that intriguing. People who’ve made lots of money out of music basically, arent they? Nothing wrong with that, and some of them have even created an interesting tune or two along the way. But not so interesting that I’ve wanted to hear their composer/performers speak. And let’s be clear here: David at one point in his career, particularly at the early 80s peak of his group Japan’s popularity, was very much the pop star. Except that, unlike so many of his generation who seemed to aspire to be bigger bigger best at whatever cost, David always expressed ambivalence about his fame.

In two decades of music-making, David has forged a signature sound of chameleon like variety. This is unusual in pop music, where many settle on a vein and mine it forever. David is taking risks with the variety of soundworlds he brings his particular sensibilities to bear on, as well as with the real quality in the (dis)guises wielded. There’s a seductively poetic, spiritual twist to this music that wrestles with its own internal ambiguity. At this stage, the struggle seems to be toward consciously seeking more personal honesty in the work whilst drawing the line at starkly auto-biographical content. Running in the opposite direction of much 20th century creative impulse, David (along with a few other luminaries–author Milan Kundera comes to mind) has always wanted the work to live independently of the personality of its creator.

Theres warmth in my heart when I listen to tracks like ‘Brilliant Trees,’ ‘Orpheus,’ ‘Before The Bullfight’ and the like. As an earnest declaration of intent during flippant times (David’s most stellar albums were all released during the eighties) I felt this music as a personal manifesto; songs speaking to ideas and feelings that I had thought secret. This uniquely quiet music was birthed during a loud era of marble-surfaced restaurants full of shouting punters, big snares, braying voices and conspicuous consumption.

David sings of a life that aspires to return to the source of that life, which is a religious thing to do really. And the result, in songs like ‘Weathered Wall’ and ‘Bullfight,’ is English pop music that combines the sonorous solemnity of great Protestant hymns with an occasional flurry of ecstatic affirmation reminiscent of Sufi musics. Indeed, Jon Hassell’s trumpet on ‘Brilliant Trees’ and the pentatonic warblings of ‘Words with the Shaman’ remind me of devotional musics from the world of Islam. It’s not so much the notes themselves I suspect, but the intent with which they are played. Rare, and precious, and infinitely pleasurable to hear, this music contains a soothing yet aspirational, alive quality.

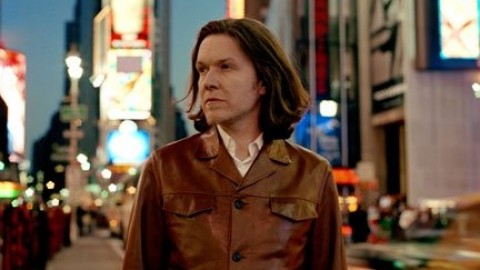

To participate in an interview this way was an adventure for me. To sit on the other side of the desk and scrutinise, assess, comment, critique. I am a working musician and composer, CDs out, gigs… see my web site. Tony Fletcher, fellow South Londoner/Crystal Palace fan in New York, is an old friend. Invited to interview David upon the release of his career ‘retrospective’ Everything and Nothing (neither greatest hits nor rarities but a little of both), Tony suggested I come with him to meet of the few I’ve wanted to.

David was charming company, and a skillful conversationalist. Adroit at secreting himself away by saying a lot without giving away the innermost material. Adroit too, at saying a lot that raises further questions and interest. I would love to have drawn him out more on the experience of South London that was common to the three of us on that table. I really wanted to hear more about his spiritual searching. And finally to have heard a little about his avowed interest to return one day to the instrumental work like Words with the Shaman which seems to be a neglected strand in his oeuvre. But I will say this, despite the foregoing, I am satiated, for his work really does say it all.

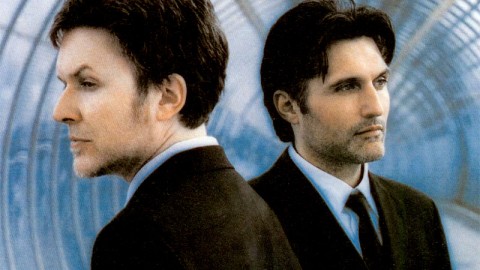

[David Sylvian’s resume is as complex as it is lengthy. Japan released four albums in the late 70s/early 80s. As a solo artist, David Sylvian has also released just four solo albums – Brilliant Trees (1984), Gone to Earth (’86), Secrets of the Beehive (’87) and Dead Bees on a Cake (’99) – but the twelve-year gap between the last two has hardly seen him idle. There were two albums with Can founder Holgar Czukay, two with King Crimson guitarist and Discipline Global Music pioneer Robert Fripp, and a Japan reformation of kinds under the name Rain Tree Crow, which yielded one album in 1991. Along with these collaborators, David has also worked extensively with Bill Nelson, Bill Frisell, Russell Mills and Ryuichi Sakamoto. It was during a recording session with the latter than Sylvian met his wife, Ingrid Chavez. The couple now have two daughters and, after stints in Chavez’ Minneapolis hometown and Sonoma County in California, have settled in New Hampshire. Considering that our conversation returned several times to the difficulties of being a cult artist on a major label, it comes as interesting news, if no real surprise, that in February this year (2001), David parted company with Virgin Records after twenty years with the label… Tony Fletcher]

GEOFFREY ARMES: Everything and Nothing. Two separate CDs. Is there any criteria at all for why certain tracks are on Everything and others on Nothing?

David Sylvian: That question has come up several times, and it’s embarrassing because no, there was none. There was purely a design element that was played up.

GA: I’ve always wondered, who is ‘Jean the Birdman.’

DS: The name came from Cocteau, but I just applied it to my life, what was going on in my life at that time. Jean the Birdman was written just after the Rain Tree Crow sessions had come to an end, and it was like a continuation of the themes that had started out on that record, the reference to the crow being this alter ego of mine and it was very much depicting the negative aspects of my own nature, the egocentric side or the anger and frustrations that I was feeling, so I just went on and wrote quite a number of pieces along the same lines, featuring the crow as a symbol of some kind, and this song was born of that period in time.

GA: ‘Weathered Wall’ has also always been a personal favorite and seems to come from somewhere quite deep, so I wondered who the ‘you’ is being addressed in that song.

DS: I wouldn’t like to pin that down, because I think it can be interpreted in a number of different ways. For me the person or the thing in question changes all the time. I like that ambiguity, I like that a song can move between being a love song to someone that’s close to you, or a God, some greater higher power, so I purposefully allow the pieces to have that ambiguity so that people can still find something of themselves in the work and work it into relevant situations in their own lives.

“I didn’t feel as if I was doctoring with anything that I shouldn’t be touching, I saw the material as being alive, and so all I was really doing was assisting in its longevity if you like, its potency for a greater number of years.”

David on recording new vocals for selected tracks on Everything And Nothing.

TONY FLETCHER: That’s something I’ve always appreciated. I love the idea that a songwriter says “This song means what you want it too mean.”

DS: Yeah, it’s very important that a piece of work becomes integrated into a listener’s life and not seen as a snippet of biography so that they’re constantly relating it to the performer’s life. It has to become relevant to their own otherwise it will have no longevity at all. So when I’m writing a piece of music you can read biographical elements into it by all means, but that’s really not the aim here. The aim is that it will take on a greater relevance in the lives of the listeners.

TF: Have you ever have to trim certain elements out, because of that?

DS: In earlier days I had trouble allowing that degree of vulnerability to come through in the work, it was often masked. I didn’t feel comfortable opening my self to that extent. But once I had a breakthrough, and ‘Ghosts’ was a pivotal piece in that sense, it was a breakthrough in which I thought I was able to talk somewhat directly about personal experiences, but in such a fashion that people could identify with it and have it be relevant in their own lives. And once I reached that stage it was a matter of just trying to stay on that path, and there was a struggle between completing a piece like Ghosts and then starting out on a new venture like ‘Brilliant Trees’: I wrote material and scrapped it, wrote and scrapped it, until something clicked with me. I think ‘Forbidden Colors’ was the next piece that clicked.

TF: What criteria have you applied for going back and effectively changing some of your past work for this retrospective album? ‘Ghosts’ [for which David recorded a new vocal] is going to be the most discussed example.

DS: There’s a number of reasons. There’s a very simple matter that Virgin owns all this material, and if I part ways with Virgin I may not always have access to it, so having the opportunity to do it was a big draw. Secondly, I’m not that fond of compilation or best of albums, because of the lack of continuity one finds: you’re not drawn into a whole experience, you’re just moving piecemeal through the individual pieces, and generally that’s down to production values from different periods in time. So I wanted to address that problem, and once I decided “I’ll have to remix Ghosts, I’ll have to remix this that nd the other,” there would be jarring transitions between songs I’ve been doing in recent years and the early ones where the vocal style is radically different. So again I thought why not? I felt if I could go back to the material and feel rejuvenated by it to the point where I could immerse myself in it and give a committed performance it would be justifiable, just as if I was giving a live performance. So I didn’t feel as if I was doctoring with anything that I shouldn’t be touching, I saw the material as being alive, and so all I was really doing was assisting in its longevity if you like, its potency for a greater number of years.

TF: What about the other Japan members who may have felt “well my bass playing could be better these days”? Did you offer the others the chance to change their parts?

DS: That would have got very complicated! I think the aspects that dated a piece like Ghosts was the vocal styling, the mannered performance, and the production values of that time. There’s lavish amounts of outboard effects, reverbs and plates, which distanced me from the material when I heard it again. So I thought I could bring it up to date…I didn’t fool around with the rest of the material. And I didn’t bring in all this outdoor gear, I kept it pure, very clean, in a sense far purer to the original recording than the mix on Tin Drum would appear. I thought about ‘Some Kind of Fool’, which wasn’t released up until now, and it crossed my mind, would everybody be happy with their performance? But everyone knew I was working on the material and no one objected.

GA: Obviously over time the vocal style evolves and I just wondered, for you, how much of this is conscious and how much of this is dictated by the fact that your instrument changes anyway. As years go by, things happen to voices and one’s physicality changes and you have to work with it.

DS: A lot of it has been conscious. Once the band broke up in 82, there was this massive change in outlook and approach to the work I was creating, trying to write more directly from my own experience meant I was trying to pare away all mannerism or declaration from the work, trying to pare it down. So I was trying to develop a vocal style that also was true to that philosophy. I was trying to find my true voice. I was trying to perform in a very unmannered way, I was trying to find means of just letting the song come out, and that meant just letting go, relaxing,

GA: That’s what I was wondering. Whether just because you were going to a different place to sing from, it would dictate your voice.

DS: that had a lot to do with it. Just as giving up drinking and cigarettes had a lot to do with it. There are physical changes and there are the changes that I try and bring to bear on the performance, trying to hone in on what I feel is the emotional intensity of a piece, and how I can best put that across as a vocalist. For me it’s a very unmelodramatic performance, I’m looking for something as understated as I can perform.

TF: You refer to doing these mixes because virgin own the masters, and I’ve seen other comments elsewhere, so there’s obviously something weighing on your mind about how long you will be on Virgin. Why is that weighing on your mind?

DS: Because the industry has changed so much in the past few years. I think it’s in the most deplorable state I’ve witnessed since I’ve been working in the industry. It really hit home when EMI bought into Virgin, kicked out a lot of good people, the atmosphere in the company changed overnight, there was a element of fear brought in, everyone looking over their shoulders, how long would they be in the position that they’re in? There was no one person sitting there who could give me a clear answer to any request. If I said, “I would like to make this kind of music,” they’d be like, “We’ll see, we’ll get back to you.” Whereas before I was always dealing with one person who would say “Go ahead, here’s the money.” And ever since that time I’ve just felt this great sense of insecurity within the label, within the employees within the label, and I’m sure this isn’t only true of Virgin. And obviously they’ve dropped an enormous number of artists over the years, and I’m just surprised I’ve hung in there! I tend to think of it only being a matter of time, it’s not something I’m necessarily afraid of, it’s just being aware that it could happen any day. There is no security for artists or employees at these major labels and this fearful atmosphere where nobody is really secure of their future doesn’t make for a healthy environment to nurture talent. In fact I don’t see any nurturing going on at all

TF: You’re right that the industry is in a dramatically different state right now, and yes, Virgin has stuck by you. It used to be enough that a major label could sell enough records around the world by a cult artist like you to make their money back. Does Virgin make enough from you around the world?

DS: Well they cover their costs. Is that enough? I don’t know.

TF: Because it’s very clear that you have pockets of healthy sales around the world.

DS: And it changes from project to project. Dead Bees did surprisingly well in Germany, and the other albums hadn’t. You get an increase here, a decrease there. A lot of people can’t stay with me from project to project. If I release an instrumental work, I might lose a bunch of people that were just turned on by Dead Bees, then they hear Approaching Silence and they’re like “What’s that all about?” and they don’t pick up on the work that follows after that. I understand why that is the case. But somehow it all seems to balance itself out in the long run.

TF: A lot of artists have come off major labels in the last few years, and some of them have become more comfortable in that, because they recognize that they’re not platinum artists.

DS: To have control over your work. . .I have control over every aspect right now, but it’s like pulling teeth trying to get the full support of a company behind you. It’s really hard to work with indifference, you can work with just about anything but indifference. There’s been an enormous frustration from my side trying to rally the troops around the work. Everybody’s enthusiastic about it, they like what they hear, but they don’t find a pocket for it, they don’t know what to do for it. And I’ve been around for so long, like you say, that they maybe think that that’s it, that I’ve reached the peak, the cap in terms of the number of sales that I’m ever going to have, and they don’t give the push that might drive an album beyond previous sales. It’s very frustrating being in that position, but there are many benefits to being on a major label, just that the album is out there, it’s accessible, it is advertised to some degree, even though as I said you really have to push the company to be there for you and put the ads in. I would be quite open to being autonomous entirely off my own back either with a small label or my own label, and I’m quite open to staying with Virgin, as long as the spirit of the company is supportive and rallies around the work.

TF: Because some of the people that you work with have ended up in their own more self-controlled independent state, when I think of Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson.

DSs: Robert is a good example but it’s actually quite hard to sustain those smaller independent labels, though Robert has done a good job of it so far. Bill has been up and down with labels of one kind or another. The guys from Japan have their own label now. I know it’s difficult, it’s not easy getting the work out there and letting everyone know it exists. I asked my brother if he would still sign up to a major label again having been autonomous, and he said yeah, so there are clear benefits.

TF: I’m interested in the process of taking such a long time between albums. There are other musicians from what I would call “my generation” who have recently taken similarly long time between albums. I’m thinking of Green/Scritti Politti and Matt Johnson/The The. In those cases, their need both for artistic freedom and to catch up with a persona life superseded the need to keep putting work out there, and I was wondering if that was the same for you.

DS: Yeah, life takes over sometimes. I don’t think people realize that life can become so exciting and interesting that it can draw you away for long periods of time from creating music – and why not? Because it will come back into the work ultimately. I don’t feel the need to prove myself a prolific artist to justify my status as an artist. It seems irrelevant how many albums I put out, but rather the quality that is important. If I make a handful of albums in a lifetime that I can really stand by and say ‘that’s work I’m proud of’ I think that’s enough, as long as my life has been full enough to compensate for the small number of albums released during that period of time.

“Life takes over sometimes. I don’t think people realize that life can become so exciting and interesting that it can draw you away for long periods of time from creating music – and why not? Because it will come back into the work ultimately.”

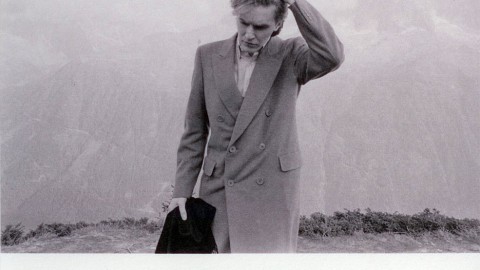

On how marriage (to Ingrid Chavez, left) and parenthood cut into recording.

I got so involved with so many things when I moved to the States, with my family, marriage, children, and then meeting certain [spiritual] teachers, that it was really hard for me to get into the studio and focus in on work. And there were periods of time when I thought well maybe that was it, that I wasn’t going to return to it, because there are other areas of life that were calling. It wasn’t that I wasn’t enjoying music – though the recording of Dead Bees was frustrating and seemed to have numerous obstacles placed in its path along its development – I just thought at some point “Maybe I’m meant to stop now, and maybe my time is up and I should be focusing on these other elements that are really fascinating me.” But it wasn’t to be so. And I’m really happy that it wasn’t so.

TF: But sometimes it takes leaving the studio and leaving the music and doing other things to have the calling of doing the music as well.

DS: It really does. And the period before that was really intense in another way, it was a very difficult period to work through, a very heavy period. And again I couldn’t really see the work, because I couldn’t really understand what it was I was living through. I was feeling incapacitated in a certain way, and very restless and every time I tried to sit down and write material it didn’t mean anything to me, I wasn’t making the connection. And I felt that it was because I didn’t understand the predicament I was in, I wasn’t able to write from that place, I was imitating myself really.

TF: You’ve built your own studio and are doing all your recording there now. Why?

DS: You tire of being in studios A lot of them aren’t particularly creative environments- not by a long shot. And I like to work slowly, and that’s costly. So to have a base where it wasn’t costing me anything was a real luxury, and when it as necessary to move out into studios or desirable to get a new perspective on the work, I tried to pick places that didn’t conform to the normal standards. That actually have quite a strong spirit. Real world obviously does; Daniel Lanois’ place Kingsway had a wonderful spirit. I just tire of being in the traditional studio environment. I can’t see myself working in that environment again. I find it totally sterile.

TF: So is the ambiance you create homely?

DS: In a sense. But it’s my space, it’s a quiet space, where I can shut the door on the world and focus in on my work, and that’s important. And I can work entirely alone. I don’t need anybody in that room with me. Which is wonderful in the writing it’s necessary, but also in the recording stage of the vocals. To be entirely alone when recording the vocals was a wonderful liberty that I had never experienced before.

TF: You loaded up with Pro Tools and all of that?

DS: It started piecemeal, we had a couple of ADATs, and Ingrid and I were doing some demos at home, and my engineer Dave Kent came into that situation and made some suggestions as to how we would improve on the set up. And we just had so many problems with the ADATs, I know some people who have had no problem at all, but I swear to God we didn’t have one tape that didn’t get mangled and destroyed in the process of recording. So we turned to the hard drive and saw that as a positive solution. We started out with something like a 4 gig hard drive and a really humble Pro Tools set up and that just expanded as the album went on.

TF: Have you turned into more of a studio buff than you once were, out of necessity?

DS: Out of necessity I have yeah. When I started out on Dead Bees, I was going to initially do it with Ryuichi. There were going to be a number of people… As I took over the production reigns entirely, we got into the Pro Tools system, I got into learning how to handle that myself, necessarily so; where other contributors had fallen short in terms of their musical contribution I had to pick that up and work that out for myself, so I was far more involved musically and on an engineering-production level than I intended. But I learned an awful lot in the process, thoroughly enjoyed it and wouldn’t have it any other way now.

TF: So there’s obviously a financial investment in terms of setting up a studio that can produce the quality of music that you’re known for, but to you that investment pays off in terms of not having to look at the clock in someone else’s studio.

DS: Absolutely. It’s a wonderful freedom to have. I’ve never been good at working under pressure. I just like taking my time on a project, I like to get to it when I’m ready, and when I am ready I like to focus in on itself. And having 1st/2nd/3rd bashes at things. Whether it’s a vocal or overdub. I remember getting to the vocals on Dead Bees four years after having written the material. It takes time to work yourself back into the material so that you get the nuances down. I would sing these songs every day until it felt right, until it was coming back at me through the speakers the way I intended it. I had never been given that luxury before – so it was a real eye opener.

TF: Although you use a lot of other musicians, I always get the impression you could play pretty much what you wanted to.

DS: Oh no, I’m definitely not a technically proficient musician, by any stretch of the imagination. I think of myself as a non-musician. I mean, I get by. I can write, and I can perform, to a certain extent, and that’s what I’ve enjoyed over the years – working with non musicians, and matching that with some beautifully technically proficient musicians that come in and play wonderfully lucid lines and performances and so on. I think of the band Japan as being a group of non-musicians. We’re all self-taught, and although we’ve matured over the years and become more proficient in what we do, there are wonderful holes in our education which will never be filled. And what that’s meant is that when you’re working together in the studio and when it comes time for a break – be it guitar or keyboard or whatever – we may not be proficient enough to take that solo, and so we have to come up with alternate means for producing something for that spot, and I’ve always found that that creative means of getting round your shortcomings was far more interesting,, ultimately, than just whacking out another solo. So I’ve loved working with Japan and the Rain Tree Crow project extended on that, and Holgar Czukay and other non musicians, because you have to find interesting ways of getting around certain problems that arise due to your lack of your technical proficiency as a player.

TF: You’re also somebody who is qualified as a visual artist, and it just occurred to me that now that one can record at home with all this equipment and you can see what you’re doing – you can see the shapes and so on. Do you see a difference in that you can see the structure of a song more in terms of a visual piece?

DS: The structure of a song is a far more internal experience for me, Yeah you can see it drawn out on the screen but I experience it differently internally. Having said that, having the ability to go right into apiece of music and fine edit performances, I go to town on that, I thoroughly enjoy it, I’m well known for editing the performances of contributors. If someone comes in and solos for me and gives me six takes, I’ll be slicing that performance up for some time, getting it just the way I want it, mixing the performances to get the performance that really suits me. The same with my vocal performances, I’ll edit it until it feels right. What I did feel about the pro tools system was that you could go to town on it, editing material over and over, refining it and refining it without killing the spirit of the piece and that was not true when working with analogue tape or digital tape. You could only go so far before you began to lose it, it would die in your head. With Pro Tools I found I could work on it endlessly, and I could in a sense enhance the spirit of a piece, in some cases the original performances weren’t really up to scratch, and I was able to bring them into focus. I remember talking to Michael Brook around the time I was making the album, and he was saying the same thing, because he was working with music that Musrat Ali Khan had done and was contributing new rhythm sections and everything to the original performances. The final album sounded so organic to me, and he said “No, it was six months sweating with Pro Tools, everything was out of time and out of tune.” And that was an eye opener for me, so I said “Okay, that’s a system I have to check out.’

GA: It seemed even more apparent on Dead Bees that kind of editing of a performers’ work. I know you said at one point you had more unsatisfactory performances, but I just wondered how you felt about how you seem to have take it to another level, taking these performances, chopping them up, and I suspect, sticking them in other songs they weren’t intended for. You felt the Pro Tools system afforded you that possibility.

DS: It liberated me. I don’t think the album could have been made without that system. I was having such difficulties getting the right performances that I saw no other options other this approach. If it hadn’t been open to me, I think it would have been lost.

GA: And in a way it cycles back to the whole thing with Holgar Czukay, because I was very struck back in ’82 when The Peak of Normal came out and there was this whole thing on the back about “painting in sound, rerecording enriched” and in a way it seem s like it’s new and it’s old. Holgar was doing it then, and you’re doing it in Pro Tools.

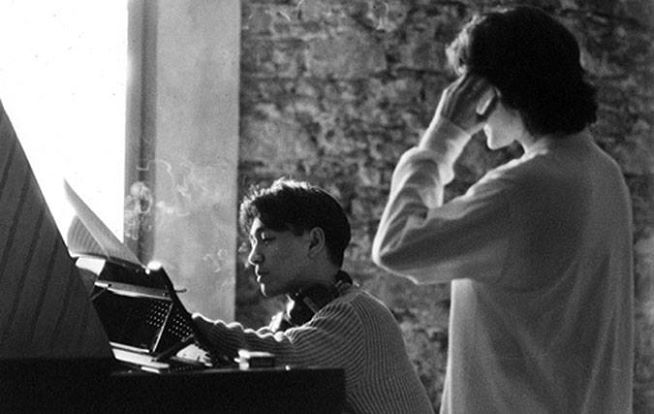

DS: That’s very true, Holgar is very much ahead of his time in the way he thinks about music and the approach he takes to editing music. I recognized that a long time ago. When I first worked with him on Brilliant Trees, he was working with these two dictaphones, and this was around the time that emulators were coming out, sampling was really just beginning to take shape, and he was saying “I’m way ahead of technology here,” just using these two IBM dictaphones. And he was, because the way he could manipulate the performances – and it was a very live, real time performance he was getting with those dictaphones – was something we were incapable of doing at that time with the samplers.

GA: On Dead Bees, I almost felt there was a kind of soul type influence in a way, and the other thing that came to mind was a 70s Steely Dan type influence.

DS: The R&B influence certainly did creep in and I think it had a lot to do with Ingrid’s listening habits. We did a lot of traveling together, and still do, and we hear a lot of music in the car so we listen to one another’s favorite albums, and I heard a lot of soul music that I had maybe heard before, but had never really listened to it to that extent. And it just played in. And another point was that I originally started out writing material for Ingrid, I was writing material for her to respond to, but after the birth of our first daughter she didn’t have time to work on material anymore, so I started focusing on my own writing, but there was a number of pieces that I had written her in mind, that I took for myself. ‘I Surrender’ was one. There are a number of pieces where I originally had Ingrid in mind.

GA: The other slightly more buried reason the soul may be there, is perhaps South London. Which connects with my talking about Holgar, because coming here I was thinking about that whole period in south London in the late 70s/early 80s, there was the soul boy thing going on, there was the dub thing, which is studio. Does that any of that resonate with you?

DS: To some extent. What I think was wonderful about growing up in London was the wonderful. . . Here, if you want to hear a genre of music, everything is segregated, you just go to the station that plays that music. When we were growing up, if you wanted to hear your favorite song you had to wade through this material [the Top 40 playlist of Radio 1]. But that gave you a wonderful education because you had to go through it whether you liked it or not. And it broadened your palate, and I think that allowed us to search out more interesting things as we grew up. I find europe a far more creative place in that extent. They’re interested in hybrids as a breeding ground for new ideas. In America, everything conforms to a certain rootsiness which I find generally uninteresting and uninspiring – though there are certain individuals who break through and embody the spirit of that genre again to some degree. But I think in Europe we are more interested in breaking new ground as artist, looking where there’s an area that hasn’t been covered before, not just melding together some hip hop with gospel but something a bit more meaningful.

GA: Also the border between high and low culture in Europe is much more blurred than it is here.

TF: Something to be said for top 40 radio. When you started out doing instrumental electronic textural music, it was still something of a very left field area, but in the years since, and this ties into home studios, there is so much of this music coming out, do you listen to much of it, do you consider yourself an influence?

DS: I haven’t heard it, I would like to I just haven’t tapped into it, I’ve been listening to people like Oval and Pan Sonic, people that are a bit more on the edge. It’s not really ambient, but sculpting sounds in such interesting ways. I don’t recognize my influence. I’m possibly the last person to see it.

TF: I’ve seen comments that suggest that you and Ingrid may yet make a record together. I’m one of, I’m sure, many people who enjoyed Ingrid’s album back on Paisley Park.

DS: The thing is, it was only critics who bought that record! I meet so many people who like that record who are critics. We’ve wanted to create work together for years now, and we were having a lot of fun mapping out territory that we felt comfortable with, particular in my writing for her, and trying to pick up on her own listening and taste and trying to second guess what might inspire her. And we did some interesting pieces together that turned up on the b-side of the ‘I Surrender’ single, but then the recording was disrupted by the birth of our first daughter and that obviously took priority and we shifted focus. We tried to get together again over the years and started writing material and it just hasn’t happened, we haven’t had the time or the focus, up until now. We’re looking at the possibility of doing it again. There’s a number of ways we can approach it. We can either make an album together, it can be a solo album for Ingrid or it can be a collective of sorts. We’re just looking at what will be the most interesting venture to undertake. Ever since the Rain Tree Crow project dissolved I’ve wanted to pick up on where that left off in terms of the approach to the work and of having a number of musicians involved in the project.

TF: The approach being collaboration?

Collaboration, a certain amount of improvisation in the writing process. The original idea for Rain Tree Crow was to have a shifting line-up of musicians from project to project, it was never meant to be a fixed line up, and I’m still very keen on pursuing that, alongside my solo work. Either Ingrid will focus on that and she’ll become a part of that line up, or we’ll pursue something more along the lines of something she would like to pursue as a writer.

“I’m very much a recording artist, I enjoy the whole process of writing and recording and arranging, or even developing a piece from scratch like Rain Tree Crow. To me that’s fascinating, stimulating and thoroughly exciting. I would focus on it exclusively and I would say it would be enough because I get so much out of it. ”

-[The tape turns at this point but my question is along the lines of: Rain Tree Crow seemed to be a very difficult project in terms of working with group members again. Why would you want to go back to that when you enjoy being so much in control of your own work?]

DS:. . .The Japan/Rain Tree Crow projects are very unique in that respect. You’ve grown up together, and as with family, you know how to push one another’s buttons. I still wouldn’t say that that’s a good reason NOT to grow together. If it’s interesting musically, it’s worth having a bash. You can overcome all the other hurdles. The Rain Tree Crow projects fell apart not in the making of the album but really just at the tail end when external pressures came to bear, so actually the relationships were working very well in the studio, it was a very exciting project to be a part of and that’s what I remember from that period of time and that’s why I would like to still create some sort of evolving compilation of musicians that could come and go. That would have been ideal of the Rain Tree Crow project but everyone felt quite possessive of it so I wasn’t able to go on and use the name and create the second line up. But I would try and stay in greater control of the overall direction of the project I guess. So there would be a direction, a vision, but within that the parameters would be pretty broad and that would create an enormous amount of freedom.

TF: Returning to the gap you took between albums. . . It was hardly like you weren’t being productive. To me that begs the question as to whether the long playing album is necessarily the proper or only form of musical communication. It’s the way record companies make their money, but in your case, you collaborate with people, you tour with people, you might put out instrumentals or a single. I was wondering to what extent you thought the album was the ultimate artistic statement.

DS: To me it’s the area of work that I enjoy the most. I’m very much a recording artist, I enjoy the whole process of writing and recording and arranging, or even developing a piece from scratch like Rain Tree Crow. To me that’s fascinating, stimulating and thoroughly exciting. I would focus on it exclusively and I would say it would be enough because I get so much out of it. But the issue I would have is the duration of these recordings. Originally we had LPs running at about 40 minutes, and now we have CDs running at 70. It would just be nice to be able to put out projects of varying duration, so if you have a piece that’s 15 minutes, you can put it out and sell it at a good price. Virgin aren’t currently interested in that approach. So at times when I’ve thought of parting ways with a major label that’s been one of the positive aspects, that I could actually start putting together projects that weren’t full blown, that I could explore for short periods and move on.

TF: That was always one of the nice things about vinyl, you had 7 inch singles and EPs, you had 10 inches and 12 inches. I think we are finally moving away from this notion that because CDs can hold 74 minutes, they have to. But it’s been a long few years of artists delivering 70 minutes of music on it, which is usually more than you need.

DS: It’s very rare that you can handle that much. We used to have the two sides of an album, and sit down for 20 minutes to listen to a side. It was nice to focus on a piece for that long. And as you say, I think the industry has recognized that it’s become too long and we’re down to about 50 minutes.

TF: Of course, Everything and Nothing is two times 70 minutes…

DS: And Dead Bees was that long too. But there’d been an absence and I thought people deserved a little more from me. I had actually been pushing for a double album for Dead Bees, because I had that much material, and also to break it up, make it a little more palatable.

TF: Have you started on new material? Do you know for sure what your next project is?

DS: No I don’t. I’m going to let that float for a while.

GA: How has your living abroad affected your perception of yourself as an Englishman?

DS: I guess I’m more comfortable with my Englishness, but it’s not something I ever carried with me that consciously. I found I began to lose my accent somewhat when I married Ingrid. She had a 7 year old son who could barely understand a word I said. I had to modify my speech to have a relationship. I don’t think people generally recognize my accent to the extent I’m English.

GA: Do you feel to any extent a stranger in America any more or less than anyone else, and do you feel you’ve arrived somewhere now, both physically and spiritually? Are you at a destination where you’re comfortable for the foreseeable future.

DS: One thing I did feel about leaving England is that having uprooted myself, I feel that I could live just about anywhere. One place is no more home than any other. I kind of glorified in that for a while, we were traveling back and forth, then that became kind of tiresome, I started to become weary of that. . . I wanted to put down roots but because my job doesn’t take me anywhere particularly, I don’t have family here, it was very difficult to find a location where we felt we belonged. Having now moved to New Hampshire, I would say there is a very good chance that we have found somewhere where we can put down roots for a number of years. A lot of this has to do with the children,

TF: How old are your daughters now?

DS: Seven and three. It was a disruption for the 7 year old, living in California for the 3 years we were there, trying to find the right school. We’ve been very fortunate here with that. We have a fair amount of land on which to grown and build a business if that’s what we choose to do. We’re building a studio, which would indicate that we’re here for some time.

TF: Do you mean a studio that other people can come and use?

DS: I don’t know about that, I think I would open the doors to friends, I can’t see it being a commercial studio right now because it’s so much part of the home. But maybe some ways down the road.

TF: Why New Hampshire?

DS: I moved to New Hampshire through contacts with my spiritual teacher. I was shown this property, it used to be an ashram . . I would never have singled out New Hampshire as a potential future home for me. It’s been a fascinating journey, not really of conscious focussed choices, it’s more a matter of following intuition, just packing up and moving on when it feels right.

TF: To what extent is the spiritual journey. . . If it’s never complete, is it ever semi complete? It seems to me you’ve found a certain amount of inner peace.

DS: Well it’s all relative. What I’ve found in teaching in the past, obviously there’s a long way to go, but the wonderful thing is that you view everything that comes up good and bad, as part of that journey, because it’s all part of the learning process, and you have something to mirror it all against. And in that sense, it pulls everything into sharper focus, so you’re less likely to be lost in an experience, to be overwhelmed by the emotions of an experience, because you can just take that slight step back to allow a certain amount of objectivity to creep in. That’s a wonderful position to be in, and I’m very fortunate that I have that capacity.

TF: You’re obviously aware there’s been this 30 year history of western musicians and eastern spirituality. You’ve played it quite carefully. Is that a certain defensiveness in that ever since the Beatles took their journey…

DS: It’s cultural tourism, that we were guilty of in Japan, and that I didn’t want to step back into. If I did step into a culture, I wanted to pull something of substance down, I would like people both from the culture into which I’m stepping as well as the western culture to appreciate it. So maybe those particular cultural influences might show in future work. But I’m taking my time with it, I don’t want to jump right in and create these superficial hybrids where we don’t develop things as far as they should go. So I’ll take my time with it and see how I digest the material. As you get older you hear so much, you listen to so much, you see so much and you find the process of assimilation is far more intuitive in the sense that when differences finally surface in the work you’re hardly conscious of it. They become part of the overall picture of your work. So I’m waiting for that process of assimilation to take place before trying to bring these influences to bear on the work. And for the work to justify itself.

Original article on ijamming.net