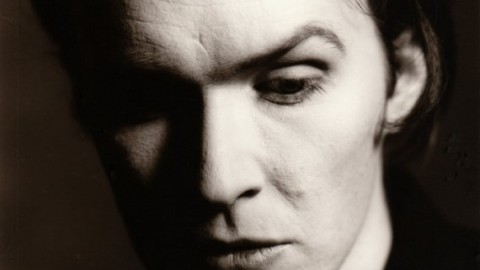

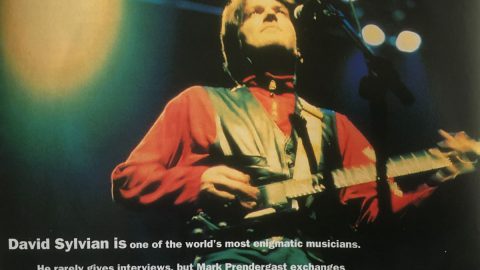

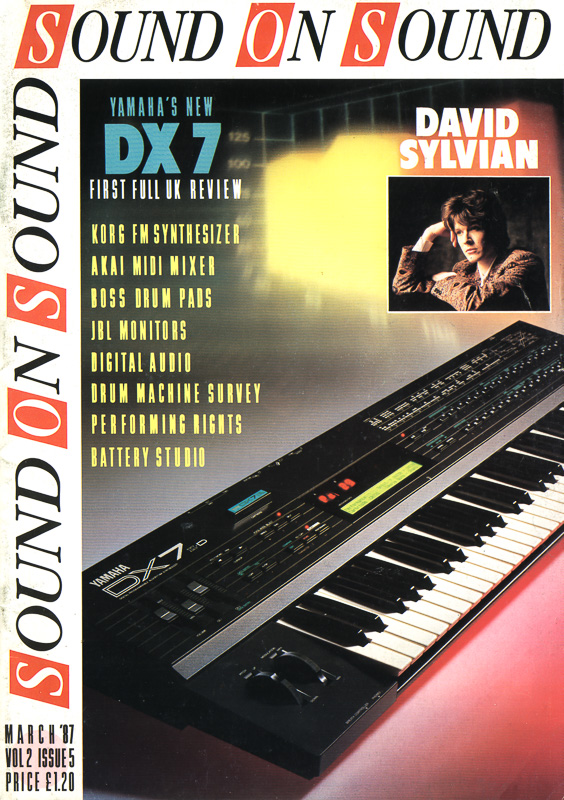

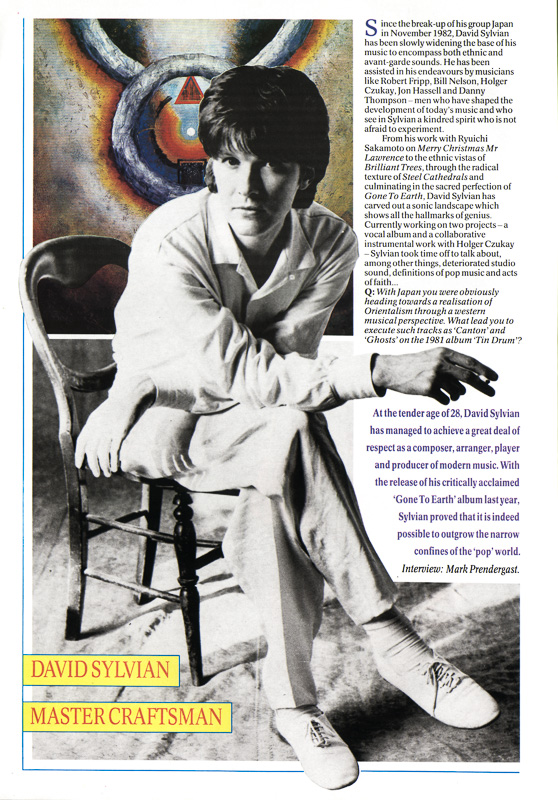

Master Craftsman

David Sylvian

by Mark Prendergast

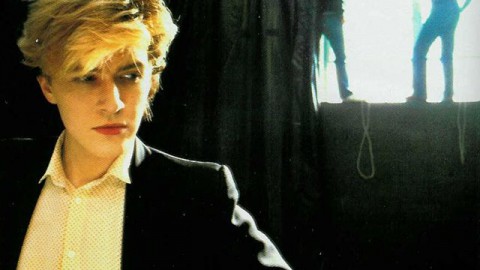

Since the break-up of his group Japan in November 1982, David Sylvian has been slowly widening the base of his music to encompass both ethnic and avant-garde sounds. Mark Prendergast gathers the facts on the change of style.

At the tender age of 28, David Sylvian has managed to achieve a great deal of respect as a composer, arranger, player and producer of modern music. With the release of his critically acclaimed ‘Gone To Earth’ album last year, Sylvian proved that it is indeed possible to outgrow the narrow confines of the ‘pop’ world.

Since the break-up of his group Japan in November 1982, David Sylvian has been slowly widening the base of his music to encompass both ethnic and avant-garde sounds. He has been assisted in his endeavours by musicians like Robert Fripp, Bill Nelson, Holger Czukay, Jon Hassell and Danny Thompson – men who have shaped the development of today’s music and who see in Sylvian a kindred spirit who is not afraid to experiment.

From his work with Ryuichi Sakamoto on Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence to the ethnic vistas of Brilliant Trees, through the radical texture of Steel Cathedrals and culminating in the sacred perfection of Gone To Earth, David Sylvian has carved out a sonic landscape which shows all the hallmarks of genius. Currently working on two projects – a vocal album and a collaborative instrumental work with Holger Czukay – Sylvian took time off to talk about, among other things, deteriorated studio sound, definitions of pop music and acts of faith…

Q: With Japan you were obviously heading towards a realisation of Orientalism through a western musical perspective. What lead you to execute such tracks as ‘Canton’ and ‘Ghosts’ on the 1981 album ‘Tin Drum’?

“It was a slow maturing process. I enjoyed writing ballads and found the slow pieces much easier to compose than up-tempo pieces – they came more naturally to me. Also, it was the influence of traditional Japanese music in its use of space – the emphasis being placed equally on the space as well as the notes played. There were also many other influences. I can pinpoint a few ideas from Stockhausen and Ryuichi Sakamoto’s wife, who recorded an album which used a ballad with very abstract synthesized melody lines behind the vocal. The song arrangements were my idea but a lot of the actual synthesizer sounds themselves came from Richard (Barbieri – Japan’s keyboard player). Because the ballad is such a recognised form of composition, a song like Ghosts allowed me a certain amount of freedom to break down the traditional ballad arrangement.”

Q: What did you like about Ryuichi Sakamoto’s approach to music making, and was there something particular about his sound that stimulated you to record ‘Forbidden Colours’, the vocal version of his theme for the film ‘Merry Christmas Mr Lawrence’ in 1983?

“After I’d decided that Japan should split, I recorded a double ‘A’ side single called Bamboo Music with Ryuichi. I’d worked with him before on the album Polaroids, so the relationship was already there. Japan were still committed to a tour and the mixing of the live album which was all done at the end of 1982. While this was being done Ryuichi sent me a tape of the soundtrack to Merry Christmas and asked me to write a lyric for it. I’d admired Yellow Magic Orchestra’s albums from the first record onwards and there was a similarity in approach to sound that could be identified in both his group and mine. I suppose it was being excited by sound and working with it on an interesting level. Ryuichi was the most accomplished musician I’d ever worked with. He’s a classically trained pianist and has worked in various areas of music, so when I first worked with him it opened up the possibilities of what writing and recording could be like.”

Q: ‘Forbidden Colours’ was recorded in Onkio Haus Tokyo with the assistance of Seigen Ono. Do you recall any particular memories of that experience?

“Well I came right in at the end of the project, just as the soundtrack was finished. I had to put this vocal on and I had an awful cold and could barely sing. It took an afternoon to put it together and I remember Onkio Haus being a nice studio to work in. Ryuichi works there a great deal and when I haven’t actually been working with him I’ve visited him there many times. I’m not a technical person. I don’t relate to technology when I walk into a studio, I relate to the atmosphere and that’s important, almost more important than the equipment in the place. Onkio Haus was a complex of four studios, but the main room, the main studio, was very well equipped and had a very good atmosphere to it.”

Between 1983 and 1984 David Sylvian spent many hours in studios in London and Berlin creating Brilliant Trees, the album which projected him out of the limited confines of ‘commercial’ music onto the broad plateau of ‘experimental’ and ‘avant-garde’ music. Here his silken vocals were enveloped by a mesmeric variety of colourful sounds ranging from Jon Hassell’s Eastern trumpet and Holger Czukay’s ‘found’ radio voices on Weathered Wall to the chanting and metal percussion at the end of the title track. The jazzy feel of Danny Thompson’s bass on The Ink In The Well coupled with the lengthy ethnic improvisations on other tracks made Brilliant Trees a stand-out release, and one that had to be taken seriously.

Q: Did working with so many innovatory musicians alter your musical understanding?

“Obviously it had a profound effect on the outcome of the album. They were all chosen for their specific roles. I tend to choose the musicians when I’m working on the arrangements of the compositions at home. For example, for the track Brilliant Trees I did the arrangement on a 4-track machine at home. I recorded the basic organ track and I had a sound on a synthesizer that was very similar to Jon Hassell’s trumpet sound. I thought that this would work perfectly and I wrote the whole end section of Brilliant Trees around the idea that Jon would be playing on it – and this was before I had made any contact with him whatsoever. (Laughs.) It tends to be the way I work, like I knew Ryuichi was going to be working with me on the album so there were certain roles that I had planned for him to play. The only person I didn’t know what to expect from was Holger Czukay. The reason I invited him was that when you are working in a band you have a constant flow of ideas, but when you are working on your own you go through lulls of trying to come up with new ideas. I wanted somebody to bounce ideas off, so that was really why I invited Holger into the studio. It worked very, very well.”

Q: Did the grouping of so many different musicians with so many different approaches and styles lead to a lot of takes and re-takes on that album?

“I like to work with people individually because it would be too difficult to have a group of musicians like Ryuichi, Holger and Jon in the studio at the same time. It would be too difficult to concentrate on everybody’s role at the same time. I prefer to work with people one-to-one and talk them through things. I think that’s the way most recording is done nowadays and it’s the way I personally like doing it.”

Q: I felt that there was a texture to ‘Brilliant Trees’ which was really wide and encompassing, something which reminded me of Jon Hassell’s endeavours to create a Fourth World Music. Was this a major ingredient in making the album?

“I really enjoyed listening to Jon’s music and it’s something that I’m interested in. I’m interested in the idea of music as a sense of place that doesn’t exactly exist in the world but it exists in the imagination of the listener or the writer. I know that Ryuichi was talking about this when we were recording Forbidden Colours and we agreed that the soundtrack of Merry Christmas had that sense of place to it but you couldn’t quite pinpoint where or what it reminded you of. Yet the place exists in the imagination of people and that’s something I wanted to bring into my work, especially on the ‘B’ side of Brilliant Trees – this sense of place, this landscape.”

This sense of landscape was to be explored in depth on Sylvian’s next project, Alchemy – An Index Of Possibilities, which contained pieces of music recorded in Tokyo and London between 1984 and 1985. It was only made available on a limited edition cassette while the Words With The Shaman trilogy of instrumentals was released as a 12-inch EP. The rest of the tape contains music specifically recorded in Tokyo during 1984 with Seigen Ono, Steve Jansen, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Kenny Wheeler, Robert Fripp, Holger Czukay and Masami Tsuchiya, for a short film titled Steel Cathedrals. This music is deliberately abstract and was recorded in an improvisatory manner that lead to a lot of tape noise being left on the finished product. Nevertheless, the sheer emotional scope of this music makes it riveting listening, something akin to flying in a dream over the North African coast and onwards over the Himalayas. How was this achieved?

“Both Steel Cathedrals and Preparations For A Journey come from the soundtrack of a video I worked on in Japan at the end of 1984. The film itself was directed by Yasuyuki Yamaguchi and he showed me some shots, just some experimental things he wanted to work on and it kind of fell in with an idea that I had of shooting the industrial areas outside Tokyo and giving it a sense of life through a pulsing sound. He went out shooting and I stayed in the recording studio. I only had eight days to do it and it was awkward because I was ill for two of those days. I really just improvised in the studio with some basic ideas that I had done in London. I put down this ‘pulse’ and then I built up an ambient atmosphere behind it, bringing in musicians to improvise over it.”

Q: Were the Arabic and French voices at the beginning Holger Czukay’s idea?

“The French voice I recorded, the rest came mainly from Holger’s use of the dictaphone. He found this old IBM dictaphone in the dustbins outside a factory in Germany and he made it work for him. Basically, he records a variety of sounds onto dictaphone tapes which are very wide and he has altered the playback head of the machine so that he can move it across the tape, backwards and forwards across the tape so that he can improvise with pre-recorded sound.

It’s the first time I’ve ever seen anybody do this with tape and the first time Holger used it was on the end section of Brilliant Trees where you can hear monks’ and women’s voices from his dictaphone. The nice thing about it is that it has a deteriorated quality – it gives this unidentifiable sound that causes very particular emotions in people. It adds colour to the music, an atmospheric depth that sounds very organic. There are sounds that we hear all the time – while we are talking you can hear sounds out on the street and you don’t have to identify particularly what they are, but when they are used in a piece of music they conjure up certain feelings which are very difficult to create with a synthesizer. I mean you would have to plan so much to find that kind of sound, but it’s something you almost stumble over when you work with Holger. I like to work with the element of chance – like Masami Tsuchiya’s ‘guitar abstractions’, which was basically him laying a guitar on the surface of a table and hitting it with different objects like a tuning fork. What came out were very much like noises.”

Q: On ‘Words With The Shaman’ you worked with a variety of musicians that included once again Jon Hassell and Holger Czukay. On the track ‘Awakening’ you build up a hypnotic ethnic instrumental piece which somehow manages to gel together the individual characters of the participants without losing anyone’s specific sound. Was this your aim?

“It was a group effort ultimately. I’d sketched out the pieces beforehand and after I came back from doing Steel Cathedrals in Tokyo, Words With The Shaman was recorded in London in 1985. I left things quite open in the studio as I always do when dealing with musicians of that calibre. I don’t try to pin things down too much, you know, but I edit a great deal afterwards and shift things around, especially with Holger’s input. I mean when I recorded that piece, Holger came along with a whole bag of cassette tapes and he would play these cassettes while the track was running and we’d record things that fell into place or nearly fell into place. They would spark off a whole set of ideas. We would then take off one sound, isolate it, and put it in different areas. Steve Jansen’s drums were built up piece by piece, they weren’t played as a whole – there was a bass drum, then a snare, then a hi-hat, and so on. Percy Jones’ bass part was sampled bits of bass from what he had improvised over the track.”

Q: You produced ‘Words With The Shaman’ with Nigel Walker. How did it feel?

“Well I’d co-produced Brilliant Trees with Steve Nye and also worked in that way on Japan’s albums. Working with Nigel was different because he was a younger engineer and I felt I could involve myself more technically in the work than I would as a rule. Normally my production credit relates to my role in the relationship between the musicians. I like to work with a producer who I have 100% trust in, who knows what I’m thinking and what I’m aiming towards, so that I can concentrate fully on the music. Making Words With The Shaman was a very hard slog, but rewarding. I’m very pleased with it and I think it’s the best thing I’ve ever done.”

Q: What aspects of modern recording interest you most?

“Oh! I don’t tend to use a lot of the studio facilities, that’s the thing. (Laughs.) When I’m working with Steve (Nye) I steer clear of all digital sounds that are coming from the keyboards I use and the effects I use. Steve steers clear of recording on digital tape and even mastering on it. I tend to prefer Holger Czukay’s approach, which is a totally idiosyncratic approach to technology – he makes it work for him in his own way and that’s what I tend to do also. I use the studio to achieve a result and I’ve basically used the studio in the same way for many years. One of the major changes over the last number of years is that most of the recording is now done in the control room. I mean a lot of the time technology can get in your way – you can hold things up for a very long time while trying to keep, say, the standard of recording quality very high. That’s something that doesn’t bother me too much… I’ve learned from Holger that the deterioration of sound quality on tape is very interesting. The sound quality from his dictaphone is very poor but that in itself is its quality – I mean all the things that go to make up the characteristics of the sound are integrated in the poor quality of the sound itself. Sometimes Steve (Nye) and I work in the studio trying to deteriorate a certain sound rather than trying to make it better! ”

Sylvian cites Brian Eno as a major influence on his work with Japan and his present solo output. He considers the studio as being a useful tool that can be adapted to any artist’s wishes. “There should be no rules, even in a studio. As soon as there are rules, even personal rules, everything becomes very safe and predictable.” Sylvian admits that his interest in music lies somewhere between the avant-garde and pop but that it fluctuates depending on what he’s aiming for in a particular piece of music. “I tend to view music emotionally and not intellectually. When I’ve reached a certain emotional layering in my work, that for me is the cut-off point.”

Q: How do you go about creating material at home?

“Well I don’t have a home studio. I just have a 4-track recorder which I sketch ideas on. I tend to write on a piano or guitar and if a song works that way I know it’ll work in any other form of arrangement. I like to leave things quite open until I’m in the studio. The tapes are used as a sketch so that the musicians can get a rough idea, and they are a very rough idea of what I’m looking for. The area of central London I live in precludes the luxury of my having 8-track equipment. I don’t really see the need for a lot of home-based equipment in the way that I work, except maybe on instrumental compositions where I work directly onto tape and build ideas.”

The release of the double album Gone To Earth in the autumn of 1986 saw David Sylvian’s art reach a zenith of perfection few could hope to equal. Over four sides of vinyl he managed to encompass an eclectic variety of musical styles which never vary in their superb quality. With Steve Jansen, Ian Maidman, Robert Fripp, Phil Palmer, Kenny Wheeler, Bill Nelson, Richard Barbieri, Harry Beckett, Mel Collins, BJ Cole and Steve Nye providing distinctive instrumental accompaniment, Sylvian managed to explore spiritual themes as evidenced by such tracks as The Healing Place, Answered Prayers and The Wooden Cross. Even though the album is divided between one ‘vocal’ record and one ‘ambient’ record, the homogeneity of his vision throughout marks the work as one of perfection. For example, the song Before The Bullfight has the slow thudding rhythm of Jansen’s drums behind the piercing guitars of Bill Nelson while Sylvian evokes a sense of duty and faith in a delicately delivered vocal. The pitch and strident structure of the song communicates the atmosphere of a bullfight, Kenny Wheeler’s flugelhorn precisely imitating the Spanish festival nature of such an event.

Q: Could you sketch out the making of this song?

“The ideas were put straight onto tape. I got a certain sound on a rhythm machine, then worked with just the drum sound. I then played around with chord shapes and recorded everything onto tape before I had any idea of what was coming next. Then I worked out the vocal to the chord shapes and I kept building, adding more guitar parts and so on. When I got into the studio I put down a click-track and a chord sequence and played the demo to my brother, Steve Jansen, who plays drums. I spent a day just doing the drums and then one by one I brought in the people who I wanted to play on the track. This was a simple piece of music and most of the recording involved me working on the atmospherics, which were the synthesizers, and then bringing in Bill Nelson to do the guitars.”

Q: The title track of the album ‘Gone To Earth’ seems to be very much Robert Fripp in that it is dominated by his complex guitar Frippertronics and even uses an old recording of JG Bennett – something which Robert is well known for?

“That was written a long time before I went into the studio and what I intended to do was a version with Robert and a version with Bill. I unfortunately ran out of time with Bill so I only had time to do the version with Robert. I just sat down with a guitar, sang the song to him and said ‘What would you do?’. He responded by saying ‘Ah! I would do something like this’, and that’s how it all started. He recorded the guitar parts all in the first take and the whole thing was spontaneous. I liked his aggressive approach, it was something that I wanted to do. The way that Robert reacted to the song was totally in keeping with what I wanted. I’d met Robert a few months earlier when we recorded Wave and he mentioned Gurdjieff and JG Bennett to me. I had been using tapes of people speaking in various ways before, so when I found some tapes of JG Bennett I decided to use them on the record. I mean I’m not afraid of allowing somebody else to have a large input into the music. I think you’d only be afraid of that if you’re a little insecure about having your personality come through a piece of music, and that in itself is not the ultimate thing.”

Q: The album was recorded in Oxfordshire and London. Which of the studios did you like the most?

“I’d have liked to have recorded it all at Shipton Manor but we ran out of studio time. The rest of the album was done in Townhouse Studios, London. I like working in the country, to be able to step outside the studio and be in a totally different environment. I have to bring myself back to earth literally because I can become too obsessive in the studio. I hated coming back to London to finish the album, I really hated doing that. I find that most of the work that was completed in London was substandard compared to the work that was completed in Oxfordshire!”

Q: This album strikes me as a very erudite piece of work – you use the voices of JG Bennett and Joseph Beuys while there seems to be a very spiritual force to both vocal and instrumental tracks. Have you been studying a lot?

“Basically I see creation as an act of faith. The whole process of recording and writing this material is an act of faith for me. In the past, all great works were based on faith and it’s only in the recent past that faith has become a dirty word, and that should be changed. Through the work it’s possible to show an appreciation of nature and a love for life and its value. Yes, it has to do with finding the true value of life within yourself and not looking for substitutes outside. My reading is more factual than literary, just reading up on subjects which help me throw light on my experiences. It covers various forms of religion and religious belief from Buddhism, Christianity to The Kabbala and some forms of magic to Rosicrucianism – just an assortment of sources that help me pinpoint the true values of life. It’s a learning process, no matter how fast you read in practice it doesn’t change you. You have to change from experience and not from intellectual reasoning.”

David Sylvian lives between London and Tokyo with his Japanese girlfriend, Yuka Fujii. She is a photographer and has contributed a lot to the visual aspect of Sylvian’s work. Recently, he has finished two 18 minute pieces of instrumental music which were recorded with Holger Czukay in the latter’s Cologne studio. There is also a vocal album on the way.

“I’m writing it at the moment and I hope to start recording it soon. It will be a departure from what I’ve been doing recently in that it will be very song based – the longest track on the album will be five minutes and the rest will be between one and three minutes. For instrumentation I’ll be going back to orchestral arrangements and traditional instruments.”

Q: You mean like flutes, oboes, cellos and violins?

“Yes!”