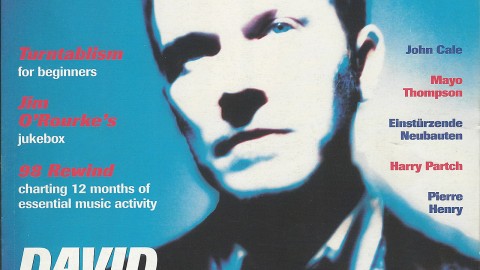

Exorcising Ghosts (Rain Tree Crow) by Mark J. Prendergast (Lime Lizard, May 1991)

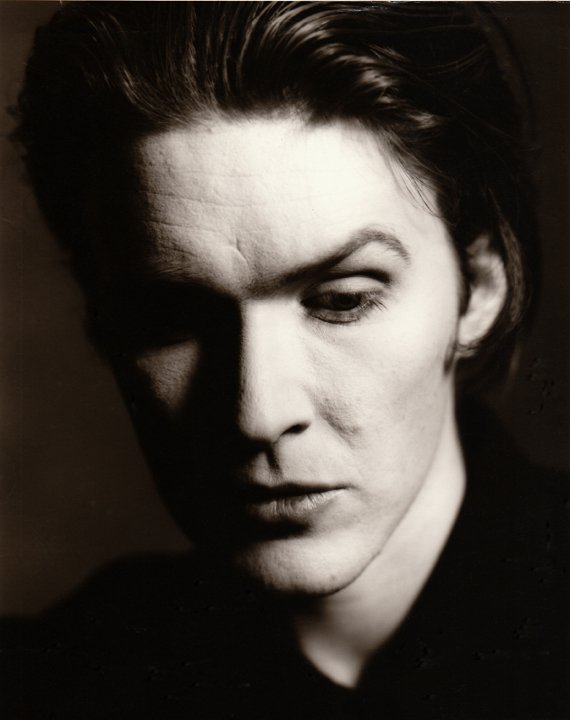

From surrealist parrots to the japan reunion, Mark J. Prendergast gets ambient with David Sylvian who explains why it’s o.k. to shout insults at bricks.

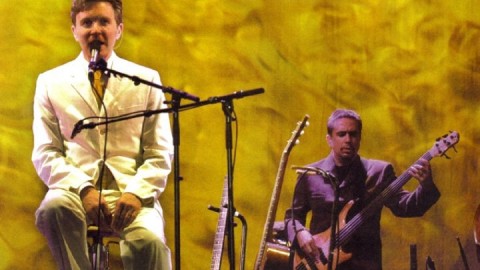

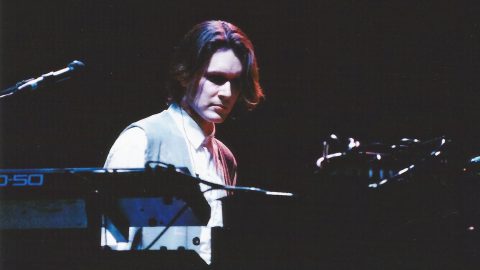

David Sylvian is that rare thing, a self conscious English artist unafraid to act and be like he thinks and feels. When Sylvian broke up Japan in the early 1980’s, he went through various states of music and philosophy. There was the Milan Kundera period as evinced on Brilliant Trees with its concoction of world, folk and jazz musics. Then a dense, mystical withdrawal into the writings of Gurdjieff and Christian philosophers via Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson and expressed through a brooding double set Gone To Earth in 1986. The following year’s Secrets of the Beehive echoed Brilliant Trees in its chamber feel but this time the lyrics were laced with Greek tragedy. An admiration for the poetical film maker Andrei Tarkovsky could be discerned in the two avant garde collaborations with Holgar Czukay Plight and Premonition and Flux and Mutability (’88-’89), two records which are spiritually very close to the music of the Russian composer Edward Artemyev – the soundtrack composer of Tarkovsky’s work.

To many peoples’ surprise, Sylvian went back into the studio in the autumn of ’89 with the other three members of Japan, Mick Karn, Steve Jansen and Richard Barbieri, simply to see what would happen. The result is a new album, Rain Tree Crow with an abstracted sound based on loose improvisation. “The desire to do it came out of the work I did with Holgar Czukay, the idea of working with improvisation to develop composition. I wanted to put myself in a position where I would have to respond to other people, to pull myself out of just writing my own material and falling into stylistic traps.”

The technique was to jam for hours in the studio. When something clicked then it was pursued. Achingly plaintive vocal tracks Blackwater or Every Colour You Are jostle for your attention amongst impressionistic instrumentals with titles like New Moon At Red Deer Wallow, Red Earth (As Summertime Ends) or Scratching On The Bible Belt.

“What justifies this record for me are those instrumental tracks. For me, that was the first time these four people worked totally hand in hand on something together. Emotionally I would say I was on a low, but I have been for some years. That’s why I’ve been working with all of these musicians (other instrumentalists were Michael Brook, Bill Nelson and Phil Palmer), going through all of these processes, struggling with these emotions in order to see if anything can give me an inkling of how to deal with these things. “At this point, David meditates on the idea of laughter alienating but tears attracting, or how a happy song might not necessarily make one feel happy: “Sometimes you need to go through a darker experience before you reach a point of understanding and permanent happiness -a sense of calm wil!lin oneself.”

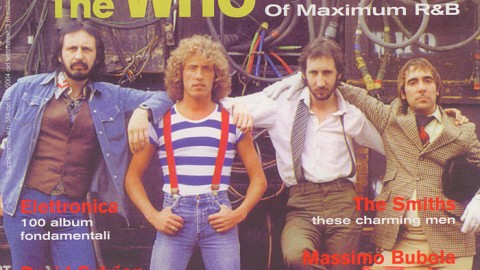

Like Van Morrison, Sylvian can only think in philosophical terms. When put under pressure to name Rain Tree Crow, the obvious Japan, with all its connotations of a reunion, touring, boxed cd sets and all the bumph that goes for contemporary music biz nostalgia, he baulked.

.The money ran out in April ’90 and a lot of pressure was put on us. People were saying if you call it Japan, you’ll get more money. It created big conflict between me and the rest of the band, I couldn’t live with it. An estrangement occurred after the record was recorded which unfortunately still remains. In the end I had to get the money together for the mixing.”

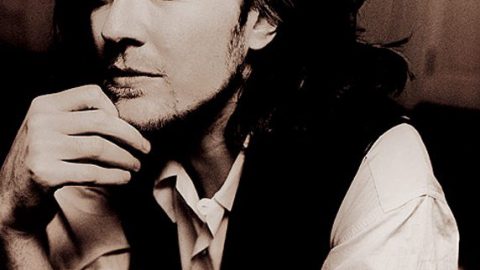

In a similar way to Max Emst, the surrealist who used the image of Loplop, a parrot, to represent himself in his art, the idea of the crow was close to Sylvian’s heart in the making of the new record. “I wanted to find an image to go with this rather heavy, bleak emotional experience I was going through. The symbol was that of a crow and that helped me objectify the experience. The lyrics are distanced in a story-telling sort of way. Actually I’ve grown quite close to him.” (Laughs).

It is true that David Sylvian is more respected as an artist abroad than in his native land. Like Eno, the problem of transiting from pop music to art is more negotiable in Italy or Japan than in ever cynical, conservative Britain. “It’s to do with education and what people’s priorities are in life. There’s no drive for self-education here. Instead, there’s a massive drive for escapism -to get away from reality at every given chance. There’s a cynicism in this country which is very destructive, a core part in the nature of many of the people. When it comes to art there’s a massive insecurity, a feeling that they’re being taken for a ride. It’s all to do with trust. You can go into a gallery and see a line of bricks on the floor. You can feel insulted by it and storm out of the gallery and say irs rubbish or you can question it.. Am I angry at these bricks? Is that a good reaction? Is that what was being intended? People here don’t think of anger as being a good response to art. People here don’t have an analytical way of analysing their own reactions.”

And so be it, until the next David Sylvian recording.