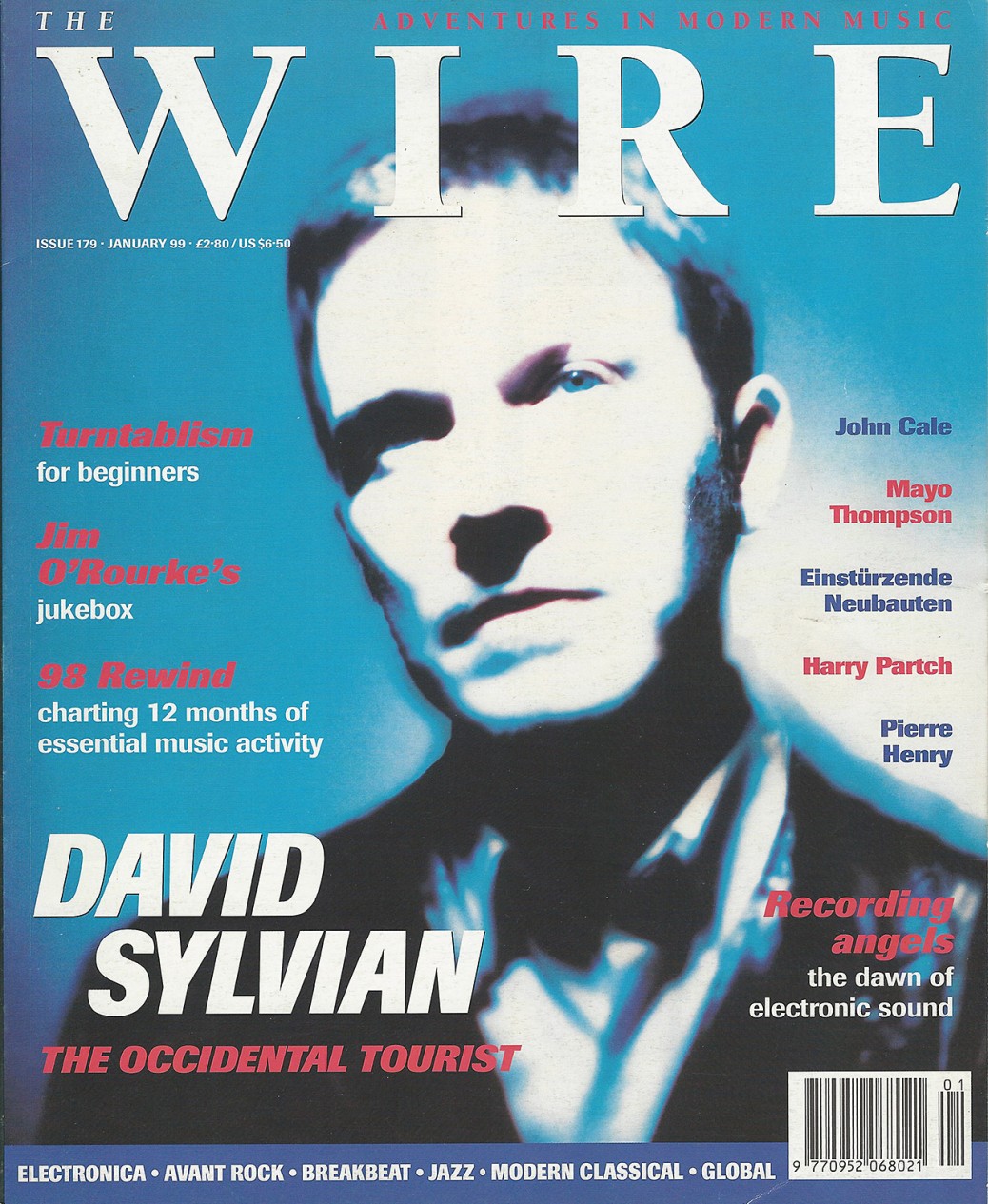

Though he’s not of this earth, David Sylvian’s music has shadowed his spiritual quest for a place on it. It’s a difficult path, but his new album says it’s worth the struggle.

Words: Rob Young

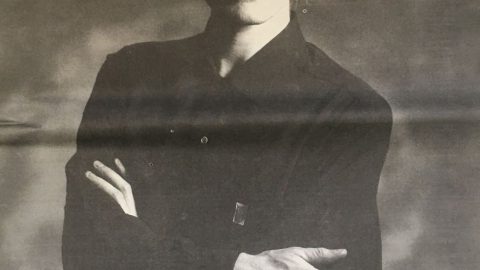

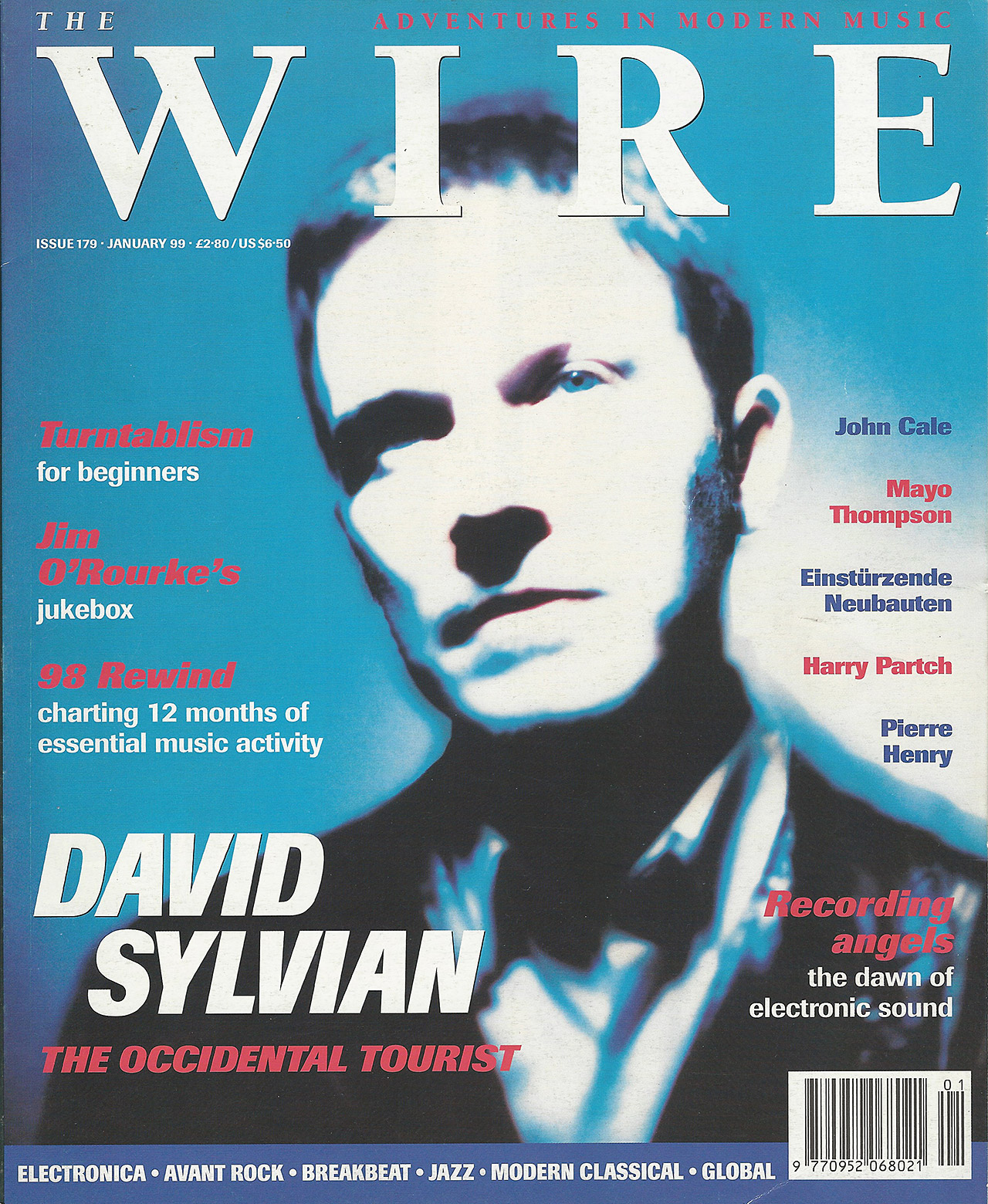

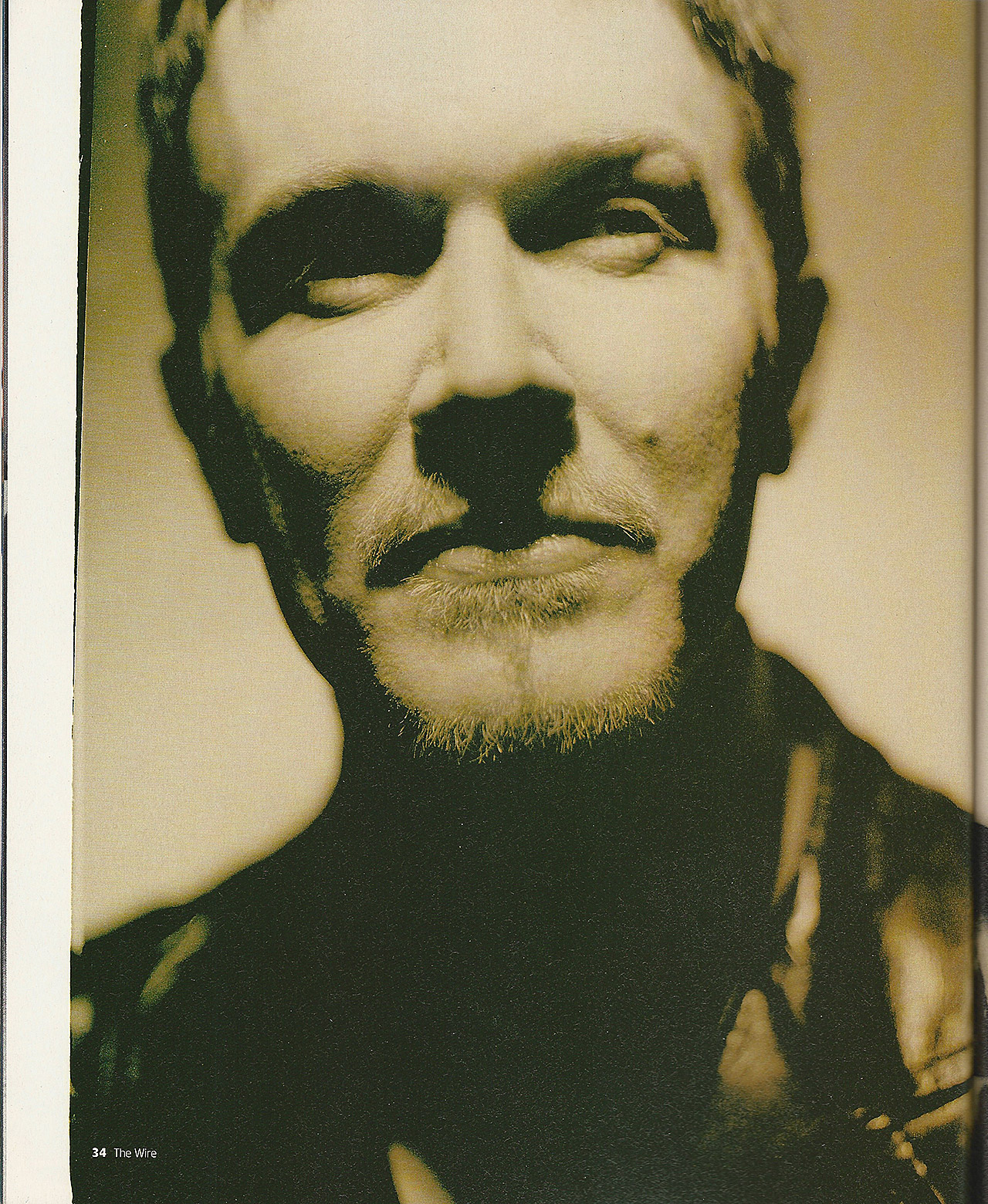

Photography: Michele Turriani

The hotel is no reeking rockers’ retreat but a bubble of Laura Ashley calm, where the clocks echo and the staff tuck tactful bills into books. The lift doors part with a swish, and he’s there, trim in a monochrome Thin White. Duke threepiece and clutching a leather jacket ‘Living abstraction’ is the new grey: white shirt, black waistcoat, cropped hair, beard shoots about the chin. Mr Sylvian sips decaff as escaping late afternoon traffic puffs smoke into the lethargic autumn air. Up the road on Kensington Gore, I’ve just sweated past my first piece of local colour the gold-leaved Albert Memorial with its architecturally shrouded statue, concealed from public view for about as long as it’s taken for David Sylvian to deliver his latest album. On the day of our interview, preparations were on the way for Albert’s gaudy, laser-daubed unveiling.

David Sylvian has likewise spent years in retreat, but there’s nothing vulgar about the way he’s breaking cover. “I don’t like elements to enter my life that I feel are unnatural,” he says, by way of justifying his long periods of invisibility “How often does the average person pick up a letter that praises them to the skies? It’s unnatural. I don’t want that, I don’t want to read that. With a new album, Dead Bees On A Cake, his best work since 1984’s glass masterpiece Brilliant Trees, Sylvian has returned as an outwardly contented New Man, a devoted husband and father, who’s found an accommodation with his subtle demons through a new, all engrossing interest in – whisper it – Oriental mysticism.

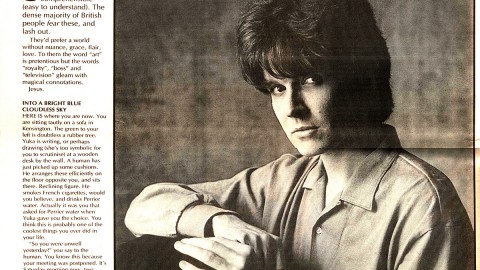

Many years ago, a British journalist, working up an interview with David Sylvian for the NME, feit compelled to put words in his subject’s mouth – words originally written by St Augustine. Though this was meant as a serious engagement with Sylvian’s body of ideas, other commentators have found him easy to lampoon: the piety; the self-absorption; lyrics of sometimes staggering pomposity – although he’s capable of equally staggering clarity and simplicity; not to mention his flirtations with mysticism and Orientalism He is not unaware of the charges of dilettantism level led against him. Referring to his collaborations with former Can bassist Holger Czukay, which include the late 80’s albums Plight And Premonition and Flux And Mutability, he says, “We feel like two non-musicians dabbling with certain instruments to pull something off in the studio” (He’s also ‘dabbled’ in painting, photography and film) Then, of course, there

are the early 80’s plastic-fantastic period press shots and record covers that just won’t go away. Japan was a different country, and they did things differently there. Where would someone like Sylvian re-settle to escape from the philistines and cynics of his homeland? Kyoto (and live up to expectations)? Berlin (and do a Bowie)? The West of Ireland (for tax reasons)? None of these. At the beginning of the 90’s, the ‘Most Beautiful Man in Pop’ escaped to the United States of America.

“Moving to Minneapolis was important in that it felt like a retreat,” he says now. “I needed to move away from England. The sense of renewal that went with the move was wonderful. Recording the album seemed part and parcel of life in the house. I was taking care of the children, working on material whenever I had a free moment. It was just part of family life in that house. Maybe I should have been more disciplined. But it just became another facet of our lives together. Also in the same period, I started seeing different teachers in different parts of the world, and that began to have an influence on my outlook.”

OK, just back up there for a second. That opening shot demands decoding. First, there’s the unshakeable image of Sylvian changing nappies, but push that to

the background for now. The ‘we’ of this solid partnership is his wife Ingrid Chavez, the American singer whom he met and married in Minneapolis. Earlier this year, having lived hidden from public scrutinyfor five years, the Sylvian’s upped sticks to the north Napa Valley in the Bay Area of California. “Wine country,” explains teetotal David with a grin.

That opening gambit also holds the key to why he headed way out west: “I made the move to Napa to be closer to one particular teacher, Shree Maa. Minneapolis was a retreat from so many things – just isolating myself I think people had the impression that I led a very isolated life here in London, but it wasn’t true. In Minneapolis I did. I had very few friends. And that’s just the way I wanted it. I led a very quiet existence, totally focused on family. Wonderful: they were five rich years that were the happiest of my life And then we retreated to the Napa hills as a family and worked closely with Shree Maa’s ashram, which is still there, for a period of months, before moving once again further along the valley. There were periods of time where that was all our locus was, the spirituality”

Most happy fella in da whole Napa Valley he might be, but as Sylvian confesses, Dead Bees On A Cake proved to be the hardest of all his records to make, even though he gathered around him three of the musicians who had brushed his earlier work with such bold strokes: Ryuichi Sakamoto, Kenny Wheeler and Sylvian’s drummer brother Steve Jansen. To stipple in the details he brought in Tommy Barbarella, Talvin Singh, Deepak Ram, Bill Frisell and Steve Tibbetts, plus various floating sessioneers. And in Marc Ribot he’s found a guitarist who could strafe and surf his compositions more accurately and gracefully than Robert Fripp, whose teethgrinding excesses scarred 1986’s Gone To Earth and the mid-90s collaborative albums The First Day and Damage.

“I started in earnest in January 95 in the basement of Ryuichi’s house in New York,” he explains “We did about three weeks’ work together – not an overly productive three weeks, surprisingly, because in the past working with Ryu, things have gone very smoothly. Normally in three or four days, we’d have enough material together. And this time we got about three days’ work out of three weeks – for some reason it wasn’t geiling. But together we got some beautiful arrangements, Ryuichi on Rhodes … Went on to record a little more in a studio in New York, that’s where Marc Ribot came in. I lelt dissatisfied generally with the turn of events, and took the material back to Minneapolis, and started re-editing and sampling what I had. I was working on Pro Tools, s0 I could really

play around with the material I spent a few months doing that then I came over to [Peter Gabriel’s studio] Real World and did a few more sessions there, which

were again very unproductive. I think I went through about three different drummers, three bassists, and it was just mindblowing, really, how little I was getting out of it. It had never happened to me before. I would shelve the album for months at a time, put it to one side, and have nothing to do with music for a while. If you condense the time, it could have been down to something like six months’ worth. But fortunately I felt the material was strong enough, because I kept going back to it and feeling refreshed by the break and by what) was hearing.”

For the first time, Sylvian took full responsibility for production. “I tend to prefer someone else to be in the mixing seat, s0 I can be more objective, but by that time I was completely over budget and it was down to myself and my engineer, Dave Kent doing it ourselves in a barn in Napa”.

Sylvian songs plumb the inevitable revelations of the subconscious, reach into the carcass of the Strong to bring forth the Sweetness of his honeyed voice. Shamanistic powers are invoked, but the modes and words remain far from violent exorcism; instead, they manifest as complex, literate distillations of emotion, philosophy and sonic wabi sabi. He be langs to that privileged cadre of globetrotting musical venturers who observe and record a version of the world through dream ticket studio hookups between ‘the right musicians for the job’. Yet Sylvian’s music, thankfully, has never aspired to, nor attained the self-knowing ‘maturity’ of a Michael Brook or Daniel Lanois. His emotional and intellectual ups and downs are a rollercoaster that travels slow enough to make the danger of falling seem real.

The down pitched folk slur of Sylvian’s singing throughout Dead Bees On A Cake is magnificent his voice is still the great crevasse at the song’s heart. “I completed the vocals in isolation in a small wood cabin tucked up in the Napa hills. It was a wonderful way of working, because I’ve never worked entirely alone before, I’ve always had an engineer or a producer present. -It gave me the freedom to record and re-record the vocals until I was happy with them” His speaking voice is much lighter than his singing voice. “I don’t sing on a daily basis, I don’t have exercises, blah blah; when it’s time to sing, I start. And it took me a while to get the nuance right for each particular song. But it was worth it. I really feel more at home with this album than with anything I’ve done in a very long time.”

The USA seems an unlikely place lor Sylvian to call home, but American tropes and traits have seeped into his latest music in the farm of beefed-up backbeats, and even a hint of swamp blues on “Midnight Sun”. For one embarking on an intense spiritual existence, isn’t it hard to screen out the nation’s crosstalk of personal, political and spiritual values?

“But there’s a great deal of optimism In America,” Sylvian counters, “and not a whole lot of cynicism when it comes to these matters And maybe a great deal of

naivety as well. From this side of the Atlantic, it’s easy to smirk a little at just how easy Americans fall for this and that. But actually I really appreciate the optimism. I wasn’t drawn to America because of its culture. I was drawn to America because of my wife, and because it was time to leave this isle, it was the logical step to take. It took me about a year to give in to liking America, to surrender to that to same degree But having done s0, I’ve really enjoyed my time there. There’s a great deal more reverence in America to teachers of all kinds. And some Americans are looked on as being very gullible because of that – but I enjoy that openness, willingness, to give something and someone a chance.

“In the way that it’s influenced my work? I can’t be sure I know that Ingrid’s taste in music has had same effect on me. Her interest in my work was primarily the songs that l’d written in the past, more so than the instrumental work, so that refocused me on writing songs again It’s not adventurous in that respect, and I daresay I won’t return to this aspect of my writing in the near future, or maybe not again. I enjoy doing it, and it’s easy for me to return to that ground and write the material. But I need to move on and stretch further – I mean, the whole process from finishing Secrets Of The Beehive [1987] up until werking on this album was really trying to explore different avenues of writing for me, that would take me out of myself. And I don’t think I really got as far as I wanted to in that venture. I enjoyed the Rain Tree Crow project [the briefly reunited Japan line-up that produced one album in 1991], and I think that was heading somewhere before it all fell to pieces. I wasn’t happy with the work I did with Robert [Fripp] particularly. Robert was leading things a little more than I was; he instigated the project, but I never felt I got to grips with it. It wasn’t a particularly stable time in my life either, s0 I didn’t feel focused on the work at all.

“So,” he continues, “the kind of ‘R&B’ aspect of the work th at seeps through, I think that comes from Ingrid’s influence, in part, and other aspects are brought in by other musiciars. For example, the second track [“Dobro #1 “] is a dobro piece improvised by Bill Frisell, and I contributed the vocal to it. “Midnight Sun” is based around a John Lee Hooker loop. Originally it was very tongue in cheek and a piece of fun – I had no intention of recording it. I guess I’m still soaking up a lot of what’s going on around me. Actually, I travel through the States a lot. I have driven the length and breadth of it. That’s been fascinating.”

To collage or to ernalgarnate? That’s the question facing any musician constructing recorded music at the end of this century. When Raoul Hausmann established collage and photomontage as a key strategy among Berlin’s internally exiled dadaists during the First World War, the roughness of the medium naturally lent itself to interrogative, aggressive, flow-breaking and irony-injecting modes. But Sylvian embodies the tradition of the amalgam: the alchemical fusion of metals into inseparable alloys with a lustre and a consistency peculiar to themselves. “I am very aware of that process in my work,” he confirms. “It’s creating hybrids, in a way, I suppose, which is fascinating. It also relates to the musicians involved. They bring their history with them, and it becomes an integral part of the work in some way”

Where hls songs were once littered with historica I and cultural reference – in the past he’s namechecked Picasso, referenced Sartre, dropped in samples of Joseph Beuys – he’s all but erased the namedrops and made the jump from allusionist to illusionist. “Yeah, thank heavens. I think I’m less embedded in culture, if you know what I mean. I looked for relationships in culture, as there was an absence of relationships in my life. I would find relationships through reading, or through visual arts. It was important for me – I don’t want to denigrate it. Now it’s less important, because I’m fulfilled in s0 many other different ways”

Does he still feel dislocated, though? “For sure, yeah. I’ve always been an outsider. I always will beo I’m not the sort of person that can belong, even to small groups. I’m not sure I’ve ever wanted to analyse why that is – I’m happy being on the outside. I’m comfortable there. I’m uncomfortable as soon as I feel like I should belong, or I’m thought to belong to a group. I rebel against it. More often than not, I’m kicked out!”

Is that detachment still the best way of attaining wisdom? “It’s always a good time to be on the outside looking in. Some people really need to be part of a group But I’ve had the experience of fooling myself into believing that I belonged to something I didn’t. And it was s0 refreshing to let go of that illusion, and I don’t hold it any more. I don’t have the yearning for it any more”

Beauty before me beauty behind me beauty to the left of me beauty to the right of me beauty above me beauty below me.” This is what comes out of David Sylvian’s mouth when I ask him to explain his repeated flights into the imagery of bees. Apart from Secrets Of The Beehive and Dead Bees On A Cake, the new album contains a track called “Pollen Path”. Is he pointing towards the geometrie dance of the bee as it indicates the most fertile stamens to its fellow swarm? No, he replies. “The mantra came from a Joseph Campbell talk – he was referring to an American Indian tribe that followed the pollen path” Why does the bee hold such a fascination for Sylvian? “As a metaphor it shifts lts focus. I was reluctant to use it again, but that title came up [in the lyrics to “God Man”] and stayed with me for such a long time, I decided that there could be no other for this project. It became an image of intoxication for me. The desire, desiring the object of desire, and then finally surrendering to it until you disappear and become part of it. Which became a humorous but adequate metaphor for this spiritual life. Desiring the beloved to the point of total surrender, until you merge and your own self disappears within the greater whole” He shrugs “And that’s why it stayed there … ”

But why dead bees?

“Death of the ego,” he states matter-of-factly. “Letting go of yourself until you become … The terminology always sounds s0 . ” He seems to realise how awkward the notions sound when given voice, but presses ahead. “You know what I mean. You begin to merge into the one, the unity … ”

It doesn’t symbolise creative desiccation? “No, it didn’t It was always a positive image tor me, as a form of letting go There are so many little deaths on the path They’re always painful to go through, but enormously rewarding to live through and come out the other side of the intensity of the experience. If you have any degree of seriousness, you’re going to be confronted with them, and they’re going to be hard.” With a knowing look, he goes on: “It feels like that – mini-deaths, you know? The little death.”

This spiritual life, the crassness of that phrase needs deflating before we can go on talking about it ”Yes I know,” Sylvian chuckles, “it sounds so cod, doesn’t it? I

hope it doesn’t come through the work in that way. It’s more in search of a philosophy or discipline with which to focus your life, or for me to focus my life; and Ingrid felt the same way Shortly after we met, we went to visit Mother Meera in Germany, and that increased our level of devotion, and we increased the amount of time we spent applying ourselves to practice A while later we met an Indian avatar by the name of Mata Amritanandamayi, and she became my guru and is still my guru. And further down the road, Shree Maa actually came to our house in Minneapolis to stay for a period of time, and that was a tremendously transforming experience also. She brought about 13 people with her, and they camped out in the house tor a while, and it kind of turned into an ashram for about a week”

“Praise”, the penultimate track on Dead Bees, features Maa’s keening vocal, with Sylvian accompanying her at his leisure on guitar in his studio. “She used to sing the piece on the album every morning at the end of puja – worship. It was always so moving, the voice very fragile echoing through the house. This yearning, it was just tremendous. We invited her to the studio upstairs to perform the song one day, that’s how that came about. It became something that we would play at the end of our worship. I finally added the guitar part to it, and it just seemed to lift it. It’s been an important piece to us, not just in terms of our practice, but as an example of true devotion. Shree Maa is a truly devoted soul, so it’s wonderful to be able to incorporate that into the album. It’s not something I could possibly project myself. I enjoy the shadow and light in my own work, but her work is just pure light”

Is music not enough to attain transcendent states anymore? Is that why he’s gone under the spell of these gurus? “Well, music has been so many things for me,” he explains. “Sometimes it can reach that stage, where it could be enough, yes, but there needs to be a practice that enables you to sustain a connection”

The cover painting on Gone To Earth, Sylvian confides, was based on an alchemical diagram by Elizabethan mystic Robert Fludd. But unlike those underground English mystics Coil and Current 93, you won’t find him delving into alcoholic purges or addled materialisations of Egyptian royals in his version of shamanistic enquiry. “It’s too easy just to slap a symbol on something,” he says of the frequency of ‘magical’ references occurring in the current musical lexicon. “If it’s digested well enough, it will appear in the work”

Because the material has been so thoroughly chewed over, there can be a sense of darkness without chaos in the music.

“People used to say to me: ‘There’s not much anger in your work’. I always felt that the voice of anger was really muted in my work, but no less powerful for that Anger comes through in a very muffled sound that breaks through in the background of a vocal performance. Something that Holger [Czukay] added onto a track like “Weathered Wall” [trom Brilliant Trees], I would use a sound like that to indicate a frustration, or a sense of anger. It never came out in a power chord or whatever. It was more subtle than that There has been enormous chaos in my life, especially from around the time of the breaking up of Rain Tree Crow up until the making and completing of The First Day, for example The First Day documents it to some degree, but as you said, it’s not true chaos. Maybe Robert Fripp is my anchor there. I turn to him when I want to express some kind of a sense of chaos .. ”

Shortly after the Rain Tree Crow sessions, Sylvian embarked on a duet with free pianist Keith Tippett that remains unfinished. “At the time I was listening to a lot of free jazz, and I wanted to get to grips with some of that, as a vocalist – not in terms of me improvising, necessarily But I ca me up with a basic structure which I let Keith go to town in, and my intention was, and still is, to respond to what he put down on tape at some point. I’ve never got back to it, because events have taken over in the meantime, but I’m still interested enough in the material to go back and have a bash at it.”

“She throws the burning books into the sea/To find the meanings of the world inside of melts all night the stars are all alive / And I surrender” – “I Surrender”

Now that Sylvian and family find themselves in temporary accommodation in the Californian hills, following five years of stable home life, where and how does he centre himself? “It has to be internal, that centering – it has to be internal anyway. And obviously at different times, I’m more centred than others. It’s a constant process of surrender. Some people have intimated to me that taking the path of surrender is an easy option – I never felt that to be true. I’ve always felt like it’s the hardest thing to surrender your will to a higher power or whatever. Or anyone, or anything It’s not a one-time event, it’s an ongoing process that you have to constantly reaffirm in every second of your life”

The difficulty is deciding what or whome to surrender to …

“There’s a great vulnerability in all surrendering, and surrendering to another person.

You’re forever going to feellike, how much are they giving to me? Am I totally secure with this person? Are they going to reflect back the love that I’m putting out to them?

“Ingrid and I found one another. It’s a fantastic partnership. We share in everything and that’s why it works, because there is a fantastic give and take. An

enormous amount of surrendering to each other. And in the disciplines we’ve been involved in, you actively surrender to your your wife or your husband – there is actually the process of recognising the divine in your partner. Which is very healthy. But we’ve been also looking to surrender to our guru, to God, or however you choose to express that.”

In his notes to Weatherbox, the 1 989 five CD boxset of Sylvian’s solo work, Steve Lake wrote that Sylvian formed Japan when he was only 16, and was therefore

obliged to become a personality before he became a person Now that he seems to have reversed the imbalance, can he tell whether the music is coming from the same impulses that led to the formation of Japan?

“I don’t think so.” He lets a beat pass. “That’s the problem of growing up in public – you make all these mistakes, and as a young man I was completely lost. Completely ill at ease in my own body, let alone my own mind. It just shows in the work There’s a tremendous rush or push away from whoever David Sylvian was at that time; anything to disguise the fact of the real person It was because I wrote “Ghosts” that I saw the possibility for the future. That’s when everything began to change for me, and my whole motivation for making music changed. It was no longer something to hide behind. It was something to not just reveal oneself, although that was part of what was going on, but to be vulnerable, basically And for the person that I was, that was an enormous step.

“I was the kind of person that couldn’t walk into a store on my own, right up until some years after Japan disbanded. I was very neurotic, I still am, but then the case was a lot worse. So, to be able to strip away the artifice, to be able to reveal myself through my work, was mindblowing to me at the time – a real eye -opening. And I began to realise the power of music as a result and what it’s real function is.”

I can’t let you go without telling me what kind of cake it is.

He laughs, “I think everybody can decide – the cake of their dreams.

‘I”m putting a quote on the album from the poet Robert Hass. It’s saying that to write a work of celebration, it has to include a lot of darkness. And that’s what I’ve always felt about my work – it’s always been celebratory, it’s always been in praise of life But I’ve always felt it isn’t true if it doesn’t have that shadow side.”

Dead Bees On A Cake is released on 75 February on Virgin