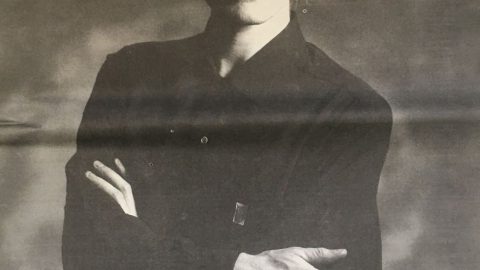

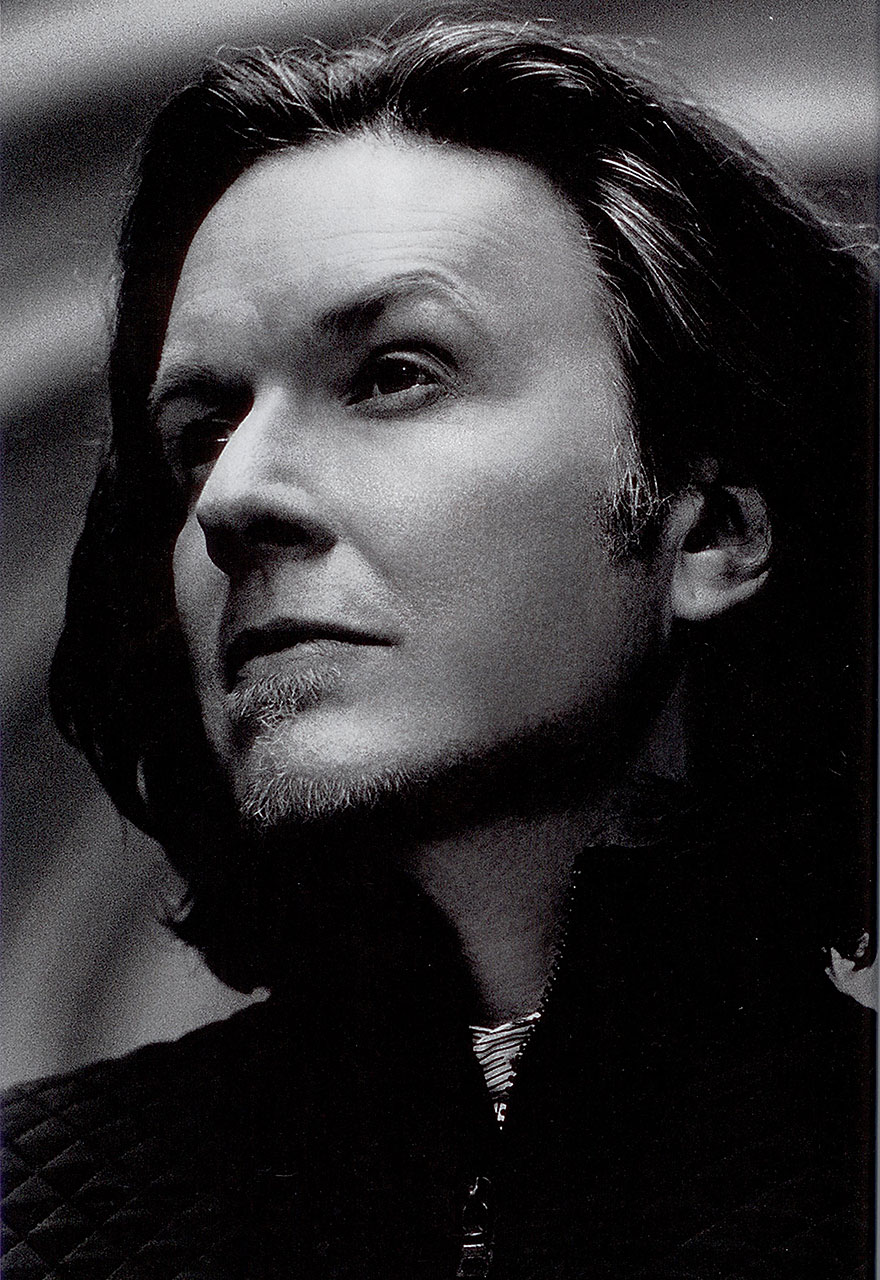

From the avant-glam pop of ]apan to free-jazz improv, he has spent three decades challenging himself. Where next for the latter-day Scott

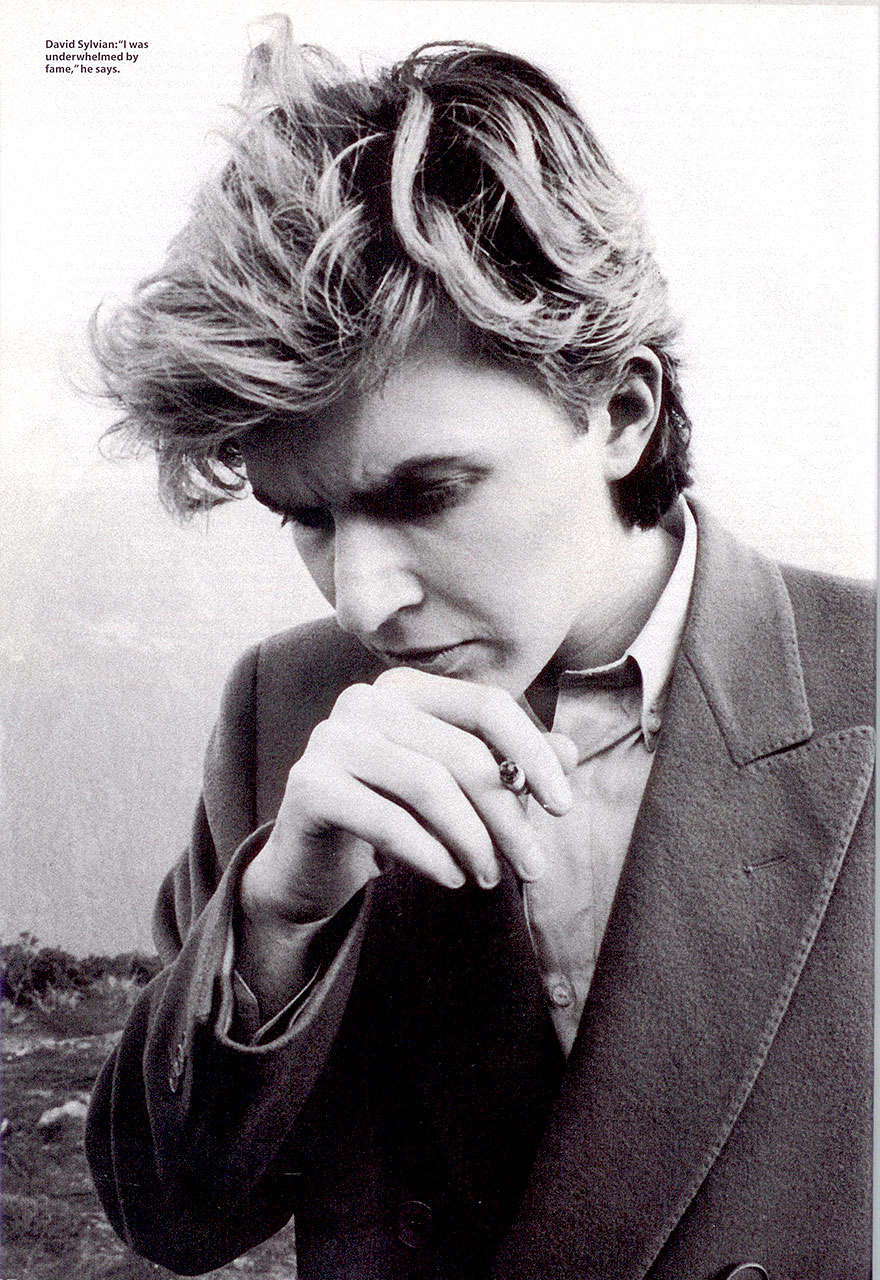

Walker? lts still all out there to be done, says David Sylvian. Interview by Phil Alexander. Portrait by Kevin Westenberg.

The pop star once marketed as the Worlds Most Beautiful Man” walks into his managers west London office in the most unassuming manner.

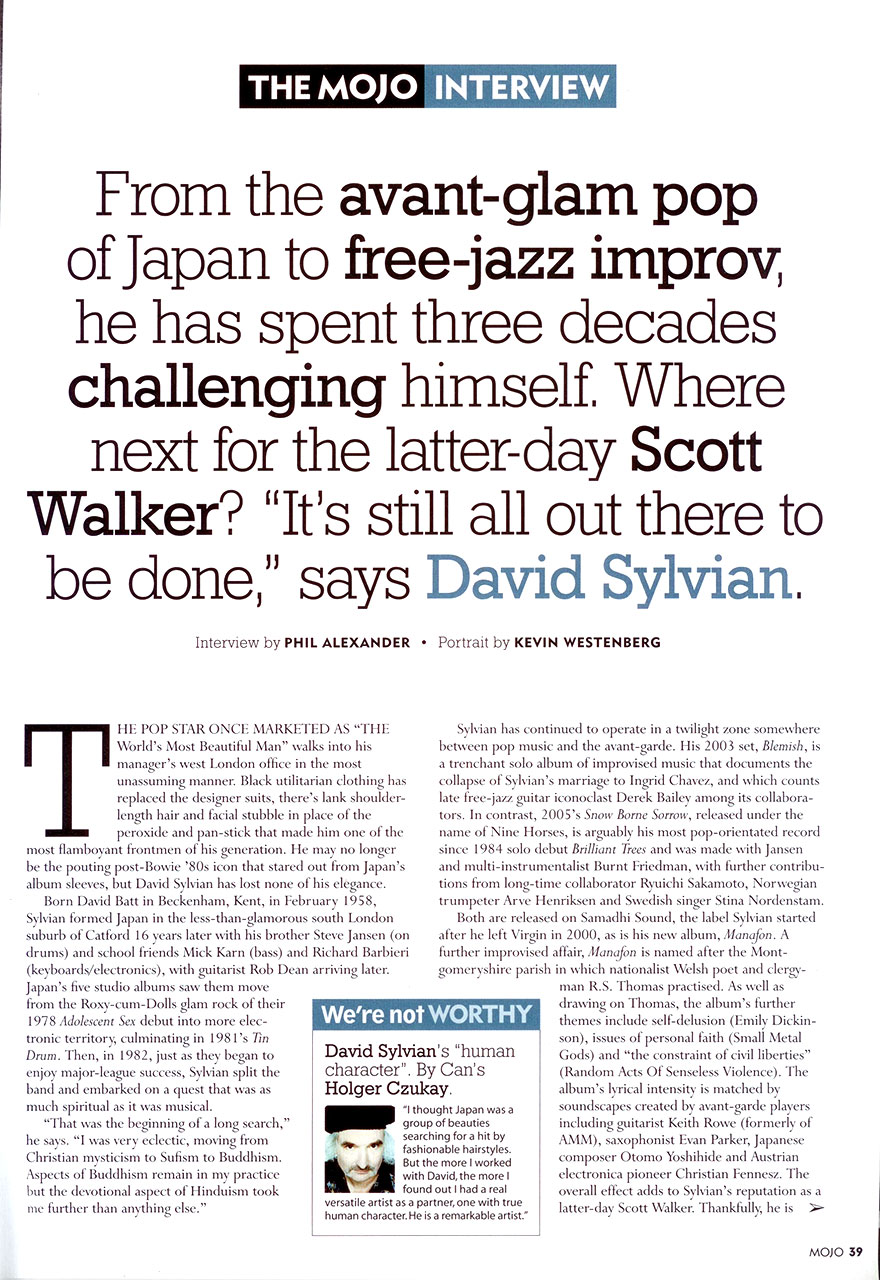

Black utilitarian clothing has replaced the designer suits, theres lank shoulder-length hair and facial stubble in place of the peroxide and pan-stick that made him one of the most fIamboyant frontmen of his generation. He may no longer be the pouting post-Bowie 80s icon that stared out from Japans album sleeves, but David Sylvian has lost none of his elegance. Born David Batt in Beckenham, Kent, in February 1958, Sylvian formed Japan in the less-than-glamorous south London suburb of Catford 16 years later with his brother Steve Jansen (on drums) and school friends Mick Karn (bass) and Richard Barbieri (keyboards/electronics), with guitarist Rob Dean arriving later. ]apans five studio albums saw them move from the Roxy-cum-Dolls glam rock of their 1978 Adolescent Sex debut into more electronic territory, culminating in 1981s Tin Drum. Then, in 1982, just as they began to enjoy major-league success, Sylvian split the band and embarked on a quest that was as much spiritual as it was musical.

That was the beginning of a long search, he says. “I was very eclectic, moving from Christian mysticism to Sufism to Buddhism. Aspects of Buddhism remain in my practice but the devotional aspect of Hinduism took me further than anything else.

Sylvian has continued to operate in a twilight zone somewhere between pop music and the avant-garde. His 2003 set, Blemish, is a trenchant solo album of improvised music that documents the collapse of Sylvians marriage to Ingrid Chavez, and which counts late free-jazz guitar iconoclast Derek Bailey among its collaborators. In contrast, 2005s Snow Borne Sorrow, released under the name of Nine Horses, is arguably his most pop-orientated record since 1984 solo debut Brilliant Trees and was made with Jansen and multi-instrumentalist Burnt Friedman, with further contributions from long-time collaborator Ryuichi Sakamoto, Norwegian trumpeter Arve Henriksen and Swedish singer Stina Nordenstam.

Both are released on Samadhi Sound, the label Sylvian started after he left Virgin in 2000, as is his new album, Manafon. A further improvised affair, Manafon is named after the Montgomeryshire parish in which nationalist Welsh poet and clergyman R.S. Thomas practised. As well as drawing on Thomas, the albums further themes include self-delusion (Emily Dickinson), issues of personal faith (Small Metal Gods) and the constraint of civil liberties (Random Acts Of Senseless Violence). The albums lyrical intensity is matched by soundscapes created by avant-garde players including guitarist Keith Rowe (formerly of AMM), saxophonist Evan Parker, Japanese composer Otomo Yoshihide and Austrian electronica pioneer Christian Fennesz. The overall effect adds to Sylvians reputation as a latter-day Scott Walker. Thankfully, he is less reticent a subject than Walker, speaking openly about his past and his work with incisive erudition

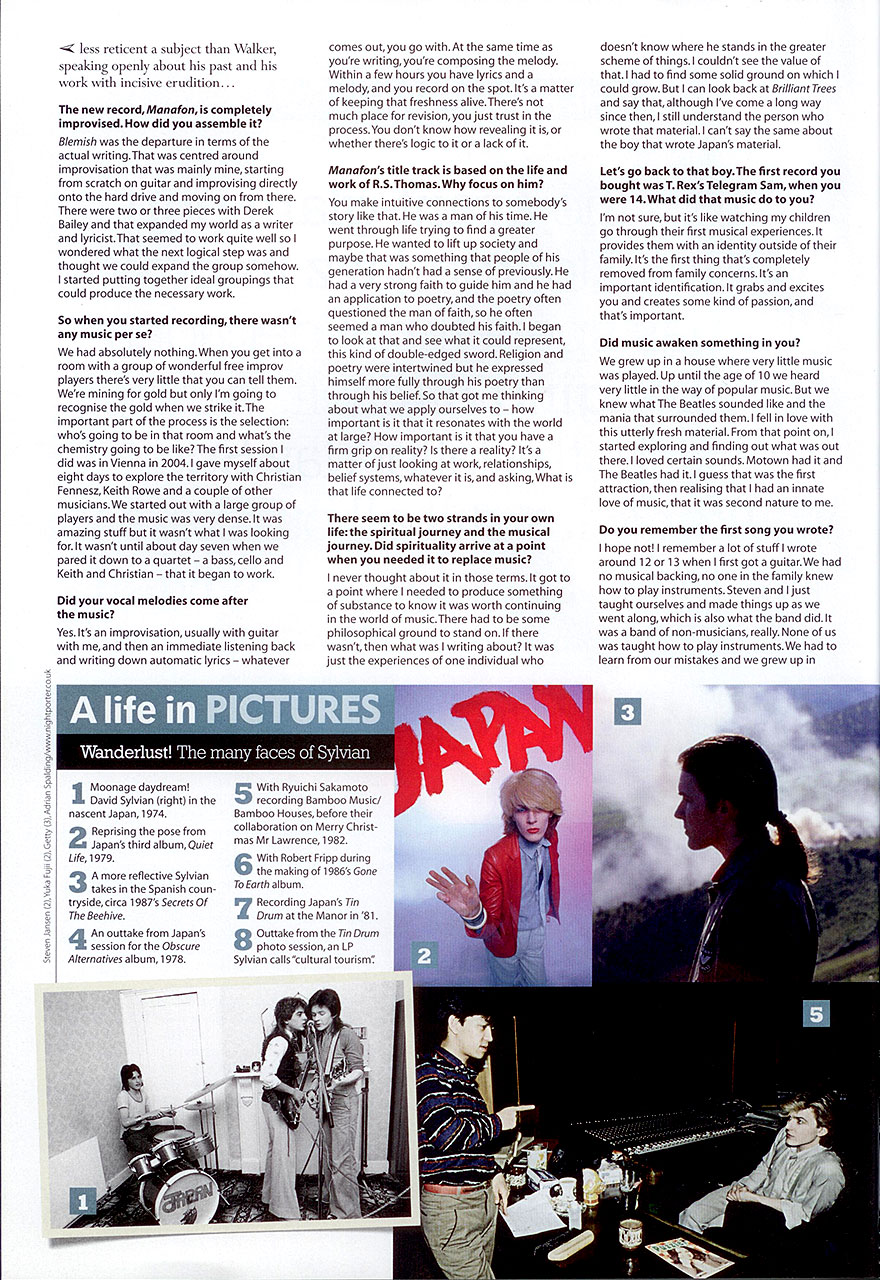

The new record, Manafon, is completely improvised. How did you assemble it?

Blemish was the departure in terms of the actual writing. That was centred around improvisation that was mainly mine, starting from scratch on guitar and improvising directly onto the hard drive and moving on from there. There were two or three pieces with Derek Bailey and that expanded my world as a writer and lyricist. That seemed to work quite well so I wondered what the next logical step was and thought we could expand the group somehow. I started putting together ideal groupings that could produce the necessary work.

So when you started recording, there wasnt any music per se?

We had absolutely nothing. When you get into a room with a group of wonderful free improv players theres very little that you can tell them. Were mining far gold but only Im going to recognise the gold when we strike it. The important part of the process is the selection: whos going to be in that room and whats the chemistry going to be like? The first session I did was in Vienna in 2004. I gave myself about eight days to explore the territory with Christian Fennesz, Keith Rowe and a couple of other musicians. We started out with a large group of players and the music was very dense. It was amazing stuff but it wasnt what I was looking for. It wasnt until about day seven when we pared it down to a quartet -a bass, cello and Keith and Christian -that it began to work.

Did your vocal melodies come after the music?

Yes. Its an improvisation, usually with guitar with me, and then an immediate listening back and writing down automatic lyrics whatever comes out, you go with. At the same time as youre writing, youre composing the melody. Within a few hours you have lyrics and a melody, and you record on the spot. Its a matter of keeping that freshness alive. Theres not much place for revision, you just trust in the process. You dont know how revealing it is, or whether theres logic to it or a lack of it.

Manafons title track is based on the life and work of R.S. Thomas. Why focus on him?

You make intuitive connections to somebodys story like that. He was a man of his time. He went through life trying to find a greater purpose. He wanted to lift up society and maybe that was something that people of his generation hadnt had a sense of previously. He had a very strong faith to guide him and he had an application to poetry, and the poetry often questioned the man of faith, so he often seemed a man who doubted his faith. I began to look at that and see what it could represent, this kind of double-edged sword. Religion and poetry were intertwined but he expressed himself more fully through his poetry than through his belief. So that got me thinking about what we apply ourselves to how important is it that it resonates with the world at large? How important is it that you have a firm grip on reality? Is there a reality? Its a matter of just looking at work, relationships, belief systems, whatever it is, and asking, What is that life connected to?

There seem to be two strands in your own life: the spiritual journey and the musical journey. Did spirituality arrive at a point when you needed it to replace music?

I never thought about it in those terms. It got to a point where I needed to produce something of substance to know it was worth continuing in the world of music. There had to be some philosophical ground to stand on. If there wasnt, then what was I writing about? It was just the experiences of one individual who doesnt know where he stands in the greater scheme of things. I couldnt see the value of that. I had to find some solid ground on which I could grow. But I can look back at Brilliant Trees and say that, although Ive come a long way since then, I still understand the person who wrote that material. I cant say the same about the boy that wrote Japans material.

Lets go back to that boy. The first record you bought was T.Rexs Telegram Sam, when you were 14.What did that music do to you?

Im not sure, but its like watching my children go through their first musical experiences. It provides them with an identity outside of their family. Its the first thing thats completely removed from family concerns. Its an important identification. It grabs and excites you and creates some kind of passion, and thats important.

Did music awaken something in you?

We grew up in a house where very little music was played. Up until the age of 10 we heard very little in the way of popular music. But we knew what The Beatles sounded like and the mania that surrounded them. I fell in love with this utterly fresh material. From that point on, I started exploring and finding out what was out there. I loved certain sounds. Motown had it and The Beatles had it. I guess that was the first attraction, then realising that I had an innate love of music, that it was second nature to me.

Do you remember the first song you wrote?

I hope not! I remember a lot of stuff I wrote around 12 or 13 when I first got a guitar. We had no musical backing, no one in the family knew how to play instruments. Steven and I just taught ourselves and made things up as we went along, which is also what the band did. It was a band of non-musicians, really. None of us was taught how to play instruments. We had to learn tram our mistakes and we grew up in public, which I dont recommend. Its the quickest way to learn, though.

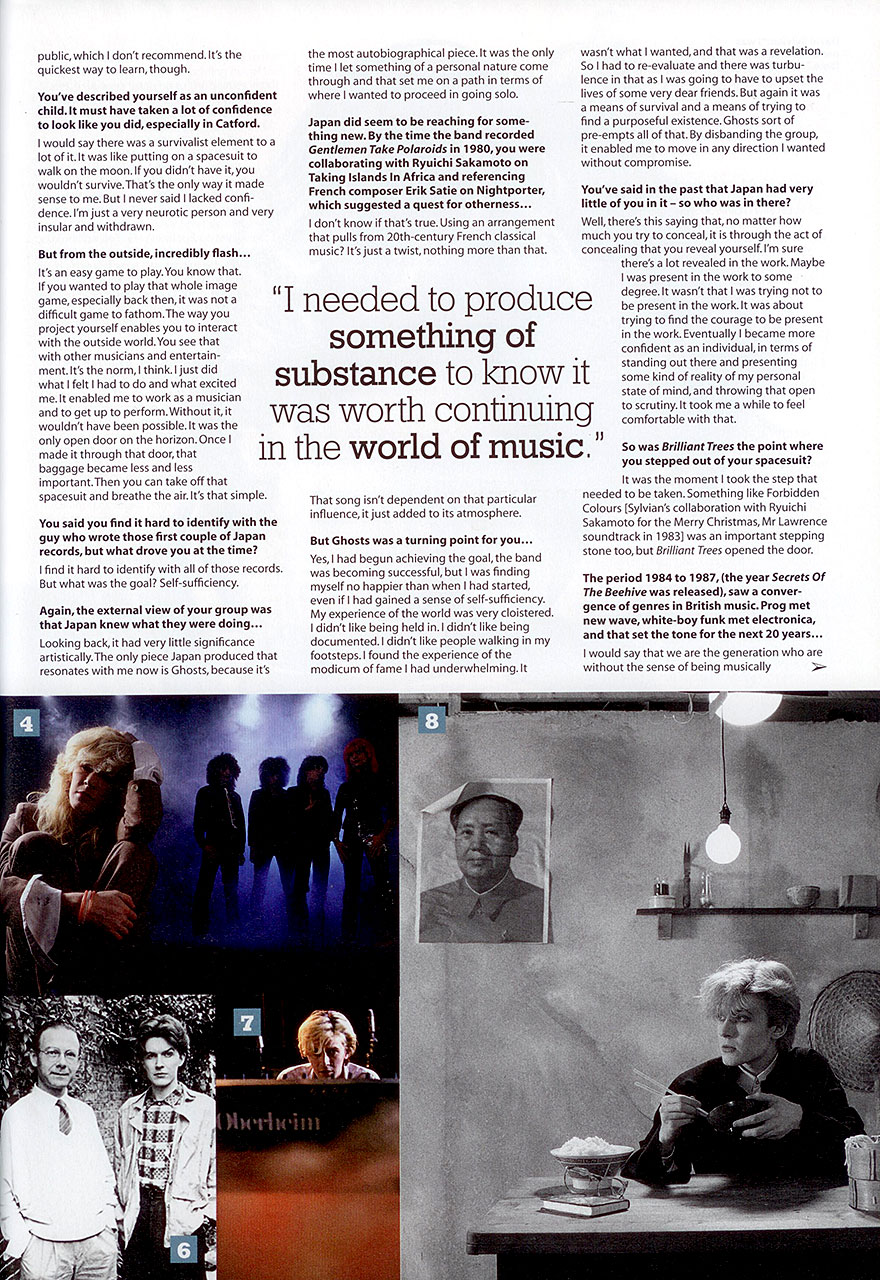

Youve described yourself as an unconfident child. It must have taken a lot of confidence to look like you did, especially in Catford.

I would say there was a survivalist element to a lot of it. It was like putting on a spacesuit to walk on the moon. If you didnt have it, you wouldnt survive. Thats the only way it made sense to me. But I never said I lacked confidence. Im just a very neurotic person and very insular and withdrawn.

But tram the outside, incredibly flash…

Its an easy game to play. You know that. If you wanted to play that whole image game, especially back then, it was not a difficult game to fathom. The way you project yourself enables you to interact with the outside world. You see that with other musicians and entertainment. Its the norm, I think. I just did what I felt I had to do and what excited me. It enabled me to work as a musician and to get up to perform.

Without it, it wouldnt have been possible. It was the only open door on the horizon. Once I made it through that door, that baggage became less and less important. Then you can take off that spacesuit and breathe the air. Its that simple.

You said you find it hard to identify with the guy who wrote those first couple of Japan records, but what drove you at the time?

I find it hard to identify with all of those records. But what was the goal? Self-sufficiency.

Again, the external view of your group was that Japan knew what they were doing

Looking back, it had very little significance artistically. The only piece Japan produced that resonates with me now is Ghosts, because its the most autobiographical piece. It was the only time I let something of a personal nature come through and that set me on a path in terms of where I wanted to proceed in going solo.

Japan did seem to be reaching far something new. By the time the band recorded Gentlemen Take Polaroids in 1980, you were collaborating with Ryuichi Sakamoto on Taking Islands In Africa and referencing French composer Erik Satie on Nightporter, which suggested a quest for otherness…

I dont know if thats true. Using an arrangement that pulls tram 20th-century French classical music? It’s just a twist, nothing more than that. That song isnt dependent on that particular influence, it just added to its atmosphere.

But Ghosts was a turning point far you…

Yes, I had begun achieving the goal, the band was becoming successful, but I was finding myself no happier than when I had started, even if I had gained a sense of self-sufficiency. My experience of the world was very cloistered. I didnt like being held in. I didnt like being documented. I didnt like people walking in my footsteps. I found

the experience of the modicum of fame I had underwhelming. It wasnt what I wanted, and that was a revelation. So I had to re-evaluate and there was turbulence in that as I was going to have to upset the lives of some very dear friends. But again it was a means of survival and a means of trying to find a purposeful existence. Ghosts sort of pre-empts all of that. By disbanding the group, it enabled me to move in any direction I wanted without compromise.

Youve said in the past that Japan had very little of you in it -so who was in there?

Well, there’s this saying that, no matter how much you try to conceal, it is through the act of concealing that you reveal yourself. Im sure theres a lot revealed in the work. Maybe I was present in the work to some degree. It wasnt that I was trying not to be present in the work. It was about trying to find the courage to be present in the work. Eventually I became more confident as an individual, in terms of standing out there and presenting some kind of reality of my personal state of mind, and throwing that open to scrutiny. It took me a while to feel comfortable with that.

So was Brilliant Trees the point where you stepped out of your spacesuit?

It was the moment I took the step that needed to be taken. Something like Forbidden Colours [Sylvians collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto for the Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence soundtrack in 1983] was an important stepping stone too, but Brilliant Trees opened the door.

The period 1984 to 1987, (the year Secrets Of The Beehive was released), saw a convergence of genres in British music. Prog met new wave, white-boy funk met electronica, and that set the tone far the next 20 years..,

I would say that we are the generation who are without the sense of being musically rooted, who didnt grow up listening to the blues and idolising what was coming out of the States. lf we were listening to The Beatles in our teens, we were really embracing the more experimental aspect of The Beatles rather than their return to more rootsy rock music. It was that sonic experimentation, like I Am The Walrus or Strawberry Fields. Then, we had the introduction and availability of synthesizers so that allowed us to develop our own aesthetic in terms of what we wanted to hear. We were the first generation to have access to that range of tonal colour, so there was a great deal of exploration on that level alone, certainly in the mid 80s. Once wed produced Tin Drum, and wed achieved what I wanted to achieve with that album sonically and in terms of the electronic arrangements of the pieces, it felt to me like it was time to move on. There were plenty of other people who were going to carry that torch.

Youve described the Oriental aspects of Tin Drum as a case of cultural tourism…

Of course it is. Thats obvious. But that led us to invent instrumentation. And that, as kids, is an exciting development. Up until that point, youd go into a recording studio and youd have a Hammond organ in that corner and a Fender Rhodes in that corner and they were things you did not touch as they belonged to the previous generation and theyd been overused. You did not want that sound on your own record. So you had to find something else. Richard Barbieri and myself would work far hours creating sounds that we identified with, using the synthesizers we had available to us at the time, and that helped create this exoticism, I suppose, that is embodied in some of Japans later work.

Once youd left Japan you collaborated with a vast roll call of very different musicians. You worked repeatedly with Holger Czukay from Can. What did you learn from him?

I learnt quite a lot from Holger, but not necessarily from the Brilliant Trees session. I struck up a wonderful friendship with him at the time. It was marked by great playfulness and inventiveness, and he would intentionally break all the technical rules in the recording process. But I loved the playfulness he brought into the studio. A sense of ‘anything goes’.

Any specific examples?

Well, at one point he was strumming his guitar and we could not get a clean sound on that guitar in the studio. So in the end I had him sitting outside the studio in a courtyard at a desk with a chair and a guitar on the table as he strummed with cables leading back into the studio. It was a very hot day and all the office workers had brought their desks out and were sitting in that courtyard. So he was sitting among these secretaries doing their work and he was having a great laugh. Between strums, hed lean aver to one of the ladies and say,

Theyre paying me a lot of money to do this, you know! He was so much fun to be with and we decided we would do something together down the line, which we did several times.

In 1990 you got back together with Steve, Richard and Mick Karn for the Rain Tree Crow project -essentially Japan by another name.

Why didnt you use the bands name?

For me, Japan isnt just these four or five individuals. Its the state of mind you were in in that period of time that created that work. And I felt completely differently as a musician, an artist, and as an individual at that point in my life than I did in 1981 or 82. But it was something I really wanted to do as a result of the improvisional work Id done with Holger [on 1988s Plight And Premonition and 89s Flux And Mutability]. I thought improvising was so interesting, so why not try it with a group of musicians? As a band we never improvised yet we knew each other well enough to trust in each other so everybody bought into it. Then we had to sell it to Virgin, which wasnt difficult, but I said that it wasnt Japan because it just didnt feel right. It was an extremely enjoyable project to work on, but it sort of fell apart at the end. But we definitely talked about doing a second or third album while we were working together.

You made two albums with Robert Fripp – The First Day in 1993 and Damage: Live in 1994. Did he ask you to join King Crimson around that time?

Hes always denied it, but yeah. I think Robert was just testing the waters. Wed worked on Gone To Earth [the 1986 follow-up to Brilliant Trees] together, we got on very well and I remember Robert saying that hed like to work with me again. I cant quite remember the circumstances but I think I just got a call out of the blue and he was on the phone asking me whether I was ready to do something. Obviously I was incredibly flattered that he asked but I think he was wrong to ask me, because I didnt think I was the appropriate candidate far the job. Also on a personal level I couldnt take on the weight of that particular baggage which wasnt mine. Id rather start something completely fresh than buy into that. And he was OK with that.

After making records with Holger and Robert, you made Dead Bees On The Cake in 1999, an album that you were genuinely happy with…

There was a long gap between finishing Secrets Of The Beehive and finishing Dead Bees… and it was a return to solo work, which I was ready far and which was a relief to get back to. It was working with very familiar forms, but advancing everything with a certain maturity. It was also the most fulfilling period of my life up until that point. I

went to the States and got married. My first child was born and Ingrid and I were on a spiritual search as well. We studied under different teachers and gurus and this was absorbed in my life in such a way that music was becoming secondary. But music was also documenting all of this experience. At the same time there would be periods where Id think that it was time to stop, that this album didnt want to be completed.

Did you genuinely contemplate giving up music at that point?

Absolutely. Not out of despair but out of a sense that there was something other taking its place. But I ended up finally bringing it to a completion. There was so much I liked about the record that I wanted it to be a double album but Virgin wouldnt go through with it. But it documented a lot of revelatory experiences in my life, joyful experiences. I felt good about it.

In contrast Blemish is a very harsh record made under some fairly trying emotional circumstances. Was it cathartic?

Totally. There’s kind of a beautiful brutality in it. Its such a clean incision. The marriage was falling apart and I explored as deeply as I could the emotions that surfaced at the time. It would be wrong to say that the content of the material was aimed at my family. It was just wanting to see how you express this while youre in the midst of it. Here I was in an extremely upsetting series of experiences, so how was I going to talk about this? The first thing I produced was Blemish, the title track, and I thought, OK, there it is. This is where Im going. It was revelatory. The process of creation was completely different than anything Id done before the automatic writing, all of that. I reached a turning point. I was eradicating the past work with something completely new in direction and process -a new process in terms of my engagement with the work and in terms of the material I’d made.

You’ve said Manafon is a continuation of the process. So are you happy now, as an artist?

Ive been really lucky to make a change in the way I approach my work. I no longer make work that I dont want to. It feels like a completely different role. The process is different because I’m not repeating myself. I feel very fortunate that I turned that corner. I’ve produced work in the last five years that sounds unlike anything else thats ever been produced before by a pop musician. That’s what I wanted to do and thats what Ive achieved. There’s a certain amount of appreciation of that fact but it feels like the tip of the iceberg. I feel I can dig so much deeper but I dont know where to dig. That’s why Ive brought things to a halt. Itll be interesting to see where that leads me next. Its still all out there to be done.