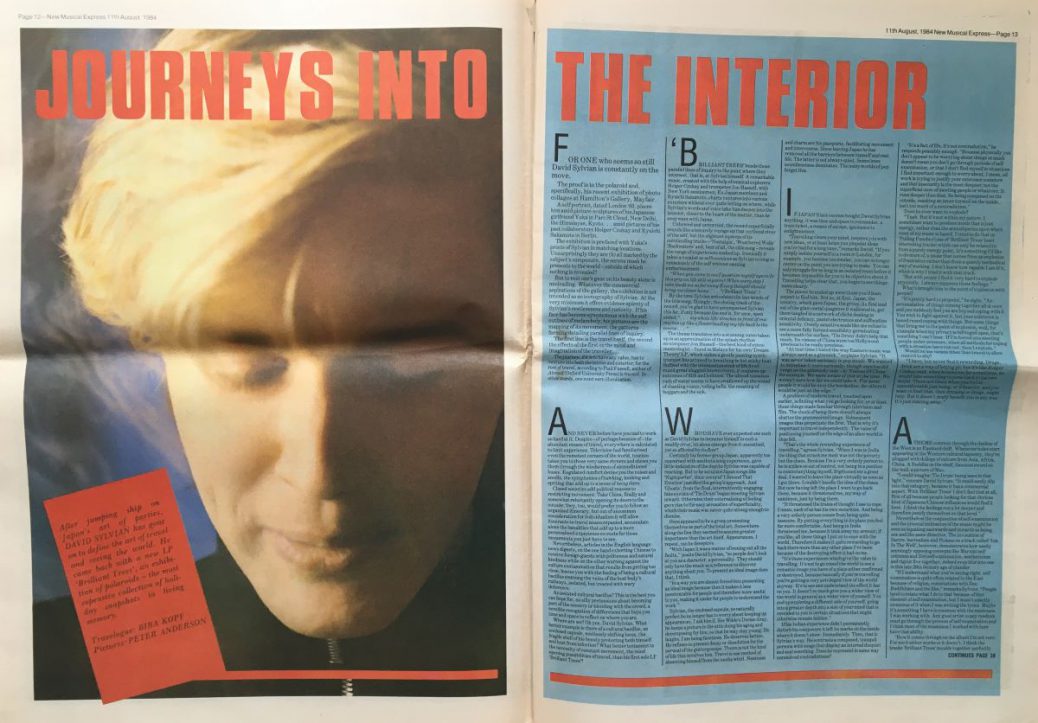

Journeys Into The Interior

Biba Kopf, New Musical Express, 11 August 1984

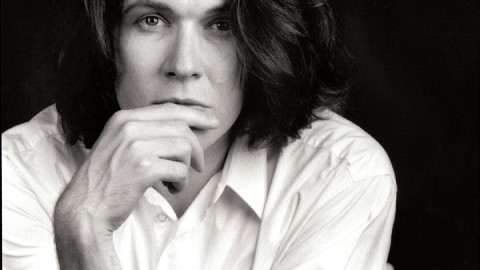

FOR ONE who seems so still David Sylvian is constantly on the move.

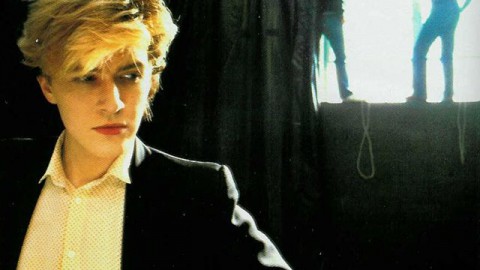

The proof is in the polaroid and, specifically, his recent exhibition of photo collages at Hamilton’s Gallery, Mayfair.

A self portrait, dated London ’83, places him amid picture-sculptures of his Japanese girlfriend Yuka in Pare St Cloud, New Delhi, the Himalayas, Kyoto…amid pictures of his past collaborators Holger Czukay and Ryuichi Sakamoto in Berlin.

The exhibition is prefaced with Yuka’s prints of Sylvian in matching locations. Unsurprisingly they are all marked by the subject’s composure, the serene mask he presents to the world – outside of which nothing is revealed?

But to rest one’s gaze on his beauty alone is misleading. Whatever the commercial aspirations of the gallery, the exhibition is not intended as an iconography of Sylvian. At the very minimum it offers evidence aplenty of Sylvian’s restlessness and curiosity. If his face has become synonymous with the soft outlines of melancholy, his pictures are the mapping of its movement, the patterns forming detailing parallel lines of inquiry.

The first line is the travel itself, the second the effects of the first on the mind and imagination of the traveller.

The journey, if it is to have any value, has to venture into both the intrior and exterior; for the root of travel, according to Paul Fussell, author of Abroad (Oxford University Press) is travail. In other words, one must earn illumination.

AND NEVER before have you had to work so hard at it. Despite – of perhaps because of – the abundant means of travel, everywhere is calculated to limit experience. Television had familiarised even the remotest corners of the world, tourism takes you to those very same corners and shows you them through the windscreen of airconditioned buses. Regulated comfort denies you the noises and smells, the symphonies of hawking, honking and spitting that add up to a sense of being there.

Closed societies add political reasons to restricting movement. Take China, finally and somewhat reluctantly opening its doors to the outside; they, too, would prefer you to follow an organised itinerary, but out of uncommon consideration for individualism it will allow itinerants to travel unaccompanied, accumulate alone the banalities that add up to a more personalised experience en route for those monuments you just have to see.

Nevertheless, articles in the English language news digests, on the one hand exhorting Chinese to receive foreign guests with politeness and natural kindness while on the other warning against the culture contamination that results from getting too close, leaves you with the feeling of being a cultural bacillus coursing the veins of the host body’s railways, isolated, but treated with wary deference.

An isolated cultural bacillus? This is the best you can hope for, no silly pretensions about becoming part of the scenery or blending with the crowd, a sensible recognition of differences that buys you time and space to reflect on where you are.

Where are we? Oh yes. David Sylvian. What better example is there of a cultural bacillus, an enclosed capsule, restlessly shifting locus, the fragile shell of his beauty protecting both himself and host from infection? What better testament to the necessity of constant movement, the mind opening possibilities of travel, than his first solo LP Brilliant Trees?

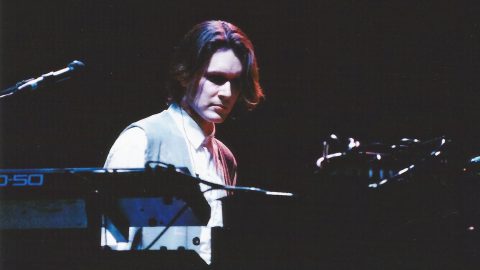

BRILLIANT TREES bends those parallel lines of inquiry to the point where they intersect, that is, at Sylvian himself. A remarkable music, created with the help of musical explorers Holger Czukay and trumpeter Jon Hassell, with New York sessionmen, Ex-Japan members and Ryuichi Sakamoto, charts ventures into various exteriors without ever quite letting on where, while Sylvian’s words and voice take him deeper into the interior, closer to the heart of the matter, than he ever went with Japan.

Unbowed and unhurried, the record superficially sounds like a leisurely voyage up that mythical river of the self, but the slightest squeeze of its outstanding tracks – ‘Nostalgia’, ‘Weathered Walls’ ‘Backwaters’ and, best of all, the title song – reveals the range of experiences soaked up. Ironically it takes a vocalist so selfconscious as Sylvian to sing so consciously of the self without causing embarrassment:

“When you come to me/I question myself again/Is this grip on life still my own?/When every step I take/leads me so far away/Every thought should bring me closer home…”

(‘Brilliant Trees’.)

By the time Sylvian articulates the last words of the title song, fittingly, the closing track of the record, you’re glad to have accompanied Sylvian this far, if only because the end is, for once, open ended: “…my whole life/streches in front of me/reaches up like a flower/leading my life back to the source…”

The theme translates into a stunning outro taken up in an approximation of the splash rhythm co-composer Jon Hassell – the best kind of ethno musicologist – found in Malaya for his own Dream Theory LP, which slakes a gentle panting synth-trumpet line attuned to breathing in hot sticky heat. Suffsed with the intoxication stink of life lived round great sluggish brown rivers, it conjures up extremes of filth and holiness. The almost noiseless rush of water seems to have swallowed up the sound of chanting voices, tolling bells, the moaning of beggars and the sick.

WHO’D HAVE ever expected one such as David Sylvian to immerse himself in such a muddy river, let alone emerge from it unscathed, yet so affected by its flow?

Certainly his former group Japan, apparently too concerned with aestheticising experience, gave little indication of the depths Sylvian was capable of reaching. But to be accurate Japan songs like ‘Nightporter’, their cover of ‘I Second That Emotion’ justified the group’s approach. And ‘Ghosts’, from the final, intermittently engaging fake exotica of Tin Drum began steering Sylvian inward. Otherwise their externalising of feeling gave rise to the easy accusation of superficiality, which their music was never quite strong enough to dismiss.

Here appeared to be a group presenting themselves as part of the total art. Somewhere along the line they seemed to assume greater importance than the art itself. Appearances, I repeat, can be deceptive.

“With Japan it was a matter of ironing out all the faults,” posits David Sylvian, “so people don’t look at you as a character, a personality. They should only have the music as a reference to discover anything about you. To present an ideal image does that, I think.

“In a way you are almost forced into presenting an ideal image because then it makes it less penetratable for people and therefore more useful to you, making it easier for people to understand the work.”

Sylvian, the enclosed capsule, so naturally perfect he no longer has to worry about keeping up appearances. I ask him if, like Wilde’s Dorian Gray, he keeps a picture in the attic doing his aging and decomposing for him, so that he may stay young. He laughs. I am being facetious. He deserves better. He refuses to present decay or dissolution for the perusal of the guttergossips. Theirs is not the kind of life that involves him. Travel is one method of absenting himself from the media whirl. Neatness and charm are his passports, facillitating movement and intercourse. Since leaving Japan he has removed all the barriers between himself and real life. The latter is not always quiet. Sometimes soundlessness dominates. The noisy worlds of pop forget this.

IF JAPAN’S late success bought David Sylvian anything, it was time and space to reconsider, a train ticket, a means of escape, ignorance to enlightenment.

“Travelling clears your mind, inspires you with new ideas, or at least helps you pinpoint ideas you’ve had for a long time,” remarks David. “If you simply isolate yourself in a room in London, for example, you become too insular, you can no longer centre on the point you are trying to make. You can only struggle for so long in an isolated room before it becomes impossible for you to be objective about it. Travelling helps clear that, you begin to see things more clearly.”

The places he ended up were those you’d least expect to find him. Not so, at first. Japan, the country, which gave Japan, the group, its first lead out of the glam metal quagmire it wallowed in, got them tangled in a net work of cliché dealing in oriental delicacy, pastel electronics and suffocation sensitivity. Overly sensitive souls like me refuse to see a more fully formed sensibility germinating underneath the surface. Tin Drum didn’t help that much. Its visions of China were too Hollywood precious to be really precious.

“At that time I hated the way Eastern music was always used as a gimmick,” explains Sylvian. “It was never taken seriously in pop music. We wanted to introduce it more seriously, though ours too did verge on the gimmicky side – in ‘Visions Of China’ for example. We were aware of that at the time. We weren’t sure how far we could take it. For some people it would be over the borderline, for others it would be just on the edge.”

A problem of modern travel, touched upon earlier, is finding what you go looking for; or at least those things made familiar through television and film. The shock of being there doesn’t always shatter the preconceived image. Subsequent images thus perpetuate the first. That is why it’s important to travel independently. The value of positioning yourself on the edge of an alien world is thus felt.

“That’s the whole rewarding experience of travelling,” agrees Sylvian. “When I was in India the thing that struck me most was not the poverty but the chaos. Because I’m a very orderly person to be in a place so out of control, not being in a position to control anything myself, frightened me a great deal. I wanted to leave the place virtually as soon as I got there. I couldn’t handle the idea of the chaos. But now having left the place I want to go back there, because it threatened me, my way of existence, just by being there.

“It threatened the trains of thought I use to cope. I mean, each of us has his own securities. And being a very orderly person comes from being quite insecure. By putting everything in its place you feel far more comfortable. And being in India threatened me, because it took away my armour, if you like, all those things I put on to cope with the world. Therefore it makes it quite rewarding to go back there more than any other place I’ve been because of the destroying effect it had on me.

“It’s those experiences which give the value to travelling. It’s not to go round the world to see a romantic image you have of a place either confirmed or destroyed, because basically if you’re travelling you’re getting a very privileged view of the world anyway. It’s to see and understand the effect it has on you. It doesn’t so much give you a wider view of the world in general as a wider view of youself. You end up exploring a different side of yourself, going into a greater depth into a side of your mind that is revealed to you in certain situations that might otherwise remain hidden.”

If his Indian experience didn’t permanently disturb his composure it left its marks on the inside where it doesn’t show. Immediately. Then, that is Sylvian’s way. He contrasts a composed, tranquil persona with songs that display an internal disquiet and soul searching. Does he represent in some way unresolved contradictions?

“It’s a fact of life, it’s not contradiction,” he responds peacably enough. “Because physically you don’t appear to be worrying about things so much doesn’t mean you don’t go through periods of self examination, or that I don’t find myself in situations I find important enough to worry about. I mean, all work is trying to justify your existence somehow and that insecurity is the most deepset; not the superficial ones of meeting people or whatever. It runs deeper than that. So being composed on the outside, masking an inner turmoil on the inside, isn’t too much of a contradiction.”

Does he ever want to explode?

“Yeah. But it’s not within my nature. I sometimes want to produce music that is just energy, rather than the atmoshperics upon which most of my music is based. I tried to do that on ‘Pulling Punches’ (one of Brilliant Trees least interesting tracks) which can only be related to from a purely energy point. It’s something I’d like to do more of, a music that comes from an explosion of frustration rather than from a quietly methodical way of working. I don’t know how capable I am of it, which is why I tried it with that track.

“But with people I find it very hard to explode physically. I always suppress those feelings.”

What’s brought him to the point of explosion with people?

“It’s pretty hard to pinpoint,” he sighs. “An accumulation of things coming together all at once and you suddenly feel you are beyond coping with it. You wish to fight against it, but your existence is based round coping with things. But some things that bring me to the point of explosion, well, for example when my privacy is infringed upon, that’s sonething I can’t bear. If I’m forced into meeting people under pressure, when all methods for coping with a situation have run out, then I explode.”

Would he use means other than travel to allow control to slip?

“I have, but never find it rewarding. Drugs, drink are a way of letting go, but it’s like Holger Czukay said, when he sees too far sometimes, he would take something to come back to his own world. There are times when you feel so uncomfortable just being, or whatever, and you want to limit that, then drinking or drugs, might help. But it doesn’t really benefit you in any way. It’s just running away.”

A THEME common through the decline of the West is an Easward drift. Whenever holes start appearing in the Western cultural tapestry, they’re plugged with dollops of culture from Asia, Africa, China. A Buddha on the shelf, Samurai sword on the wall, a picture of Mao…

“I could imagine Tin Drum being seen in that light,” concurs David Sylvian. “It could easily slip into that category, because it has a commercial aspect. With Brilliant Trees I don’t feel that at all, first of all because people looking for that obvious kind of Japanese/Chinese influences would find it here. I think the feelings run a lot deeper and therefore justify themselves on that level.”

Nevertheless the conjunction of self-examination and the oriental inclination of the music might be seen as equating eastwards and inwards as being one and the same direction. The invocation of Sartre, surrealism and Picasso on a track called ‘Ink In The Well’, however, demonstrates how easily seemingly opposing concepts like Marxist self criticism and Zen self examination, aestheticism and rigour live together, indeed even blur into one in this late 20th century age of plunder.

“If I understand what you’re saying right, self examination is quite often related to the East because of religion, connotations with Zen Buddhhism and the like,” remarks Sylvian. “People tend to relate what I do to that because of that element of self examination, but I wasn’t exactly conscious of it when I was writing the lyrics. Maybe it’s something I have in common with the musicians I was working with. Any good artist in any medium must go through the process of self examination and I think most of the musicians I worked with here have that ability.

“How it comes through on the album I’m not sure. For me it either works or it doesn’t. I think the tracks Brilliant Trees moulds together perfectly. Others I had to drop because they didn’t.”

Brilliant Trees works where Japan’s Tin Drum didn’t because Sylvian has discovered a confidence in his ability to write directly about the self. He no longer feels the need to externalise his feelings in rather grand visions of China.

Travel might trigger his writing, but it is not the subject of it. What he has to say is best heard without filters. Thus doubts about Japan’s cross cultural filchings dissolve themselves in the effortless flow of Brilliant Trees, the outstanding moments of which have the deceptive simplicity of the best metaphysical poetry.

“Maybe I wasn’t equipped to write about myself directly before,” queries Sylvain. “Even ‘Ghosts’ was an outside observation. You don’t feel the person singing the song is experiencing those feelings. ‘Brilliant Trees’, the song, is obviously something genuine. It doesn’t say anything in particular, which is something I’d hitherto always found difficult to do, to work towards something with no obvious result. I always used to work titles, a strong musical or lyrical concept, as opposed to just finding my way with lyrics. Maybe that comes with being a little more confident about my work.”

CULTURAL CONTAMINATION is no longer a crime, not even in China. “Cultural contamination,” asserts the headline of a Chinese weekly digest, “differs from criminal activities.”

It might not exactly be encouraged in China, but then the art that resulted from the cleansing era of the cultural revolution is hardly a strong argument in favour of cultural purity. Travelling this side of the divide – in these last dying years of the 20th century, western popular culture has needed all the help it can get to keep itself alive. Borders are no longer sacrosant, nor indeed should they be. Cultural cross fertilisation is a natural by product of curiosity. Here we are neither talking Coca Cola colonisation nor the Dr Livingstone tendency to bring ethno-musics back whole.

Brilliant Trees charts a course between those factions.

“It was not the original intention of the album,” Sylvian says, “it was more a matter of wanting styles of performance and it just so happens that they’re spread around the world. Once we got into the studio we became aware of it.

“A couple of tracks on the B-side of the album now conjure up the feeling of places which you can almost pinpoint, but not quite. Those aspects to me are the record’s major achievements. Managing to create something that wasn’t related to any particular place but in your own mind you could relate it to certain areas you’d been to. I think it comes from working with all these different people.”

With so many borders broached, both musically and physically, it was fitting that it should have been recorded in that ultimate bordertown, Berlin. Neutral ground for the four main contributors: Ryuichi Sakamoto fron Tokyo, Jon Hassell from New York, Holger Czukay from Cologne and Sylvian. Each brought with him different musical philosophies.

Though Hassell and Cuzkay both studied together under Stockhausen they’ve each gone different ways and this was their first encounter since student days. Hassell had forged a new music from a variety of enthic sources, remaining true to them while making them at once his own. Czukay’s dictaphone recordings from short wave bands and scattered locations, plus his distinctly primitive sweet sounding guitar put Sylvian in touch with a totally different set of sources.

Ryuichi Sakamoto’s Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence soundtrack is perhaps the closest reference point to the resulting record, insofar as both have a strong sense of place, though that place remains indefineable.

A mark of the record’s greatness is Sylvian’s ability to channel all this diversity into a unified whole shot through with his own character, but without destroying those of the participants. Where did he find a meeting point, some common ground, upon which the four could build?

“Well, people like Holger and Jon are very aware of Eastern philosophies and Ryu is obviously interested in the West,” Sylvian explains. “There is a meeting point in the middle, which is where I think a lot of us are working. Right along the borderline there is a meeting point.

“You don’t have to turn over your way of thinking to get there. It’s like religion: you take parts which are valuable to your life, of those parts that confirm things you already feel about yourself. You don’t have to latch onto it totally and accept blindly all its doctrines and disciplines.

“It’s the same in life, with the people you work with. The way to use people musically is to take a different aspect of their music or philosophy. It comes to that quite naturally. There is a natural meeting point that comes through a certain way of thinking, a certain direction. A certain line of thought that leads you to take the best of all worlds…”

Thus David Sylvian’s strategy of permanent exile. Long may he roam.