Interview by Marcus Boon

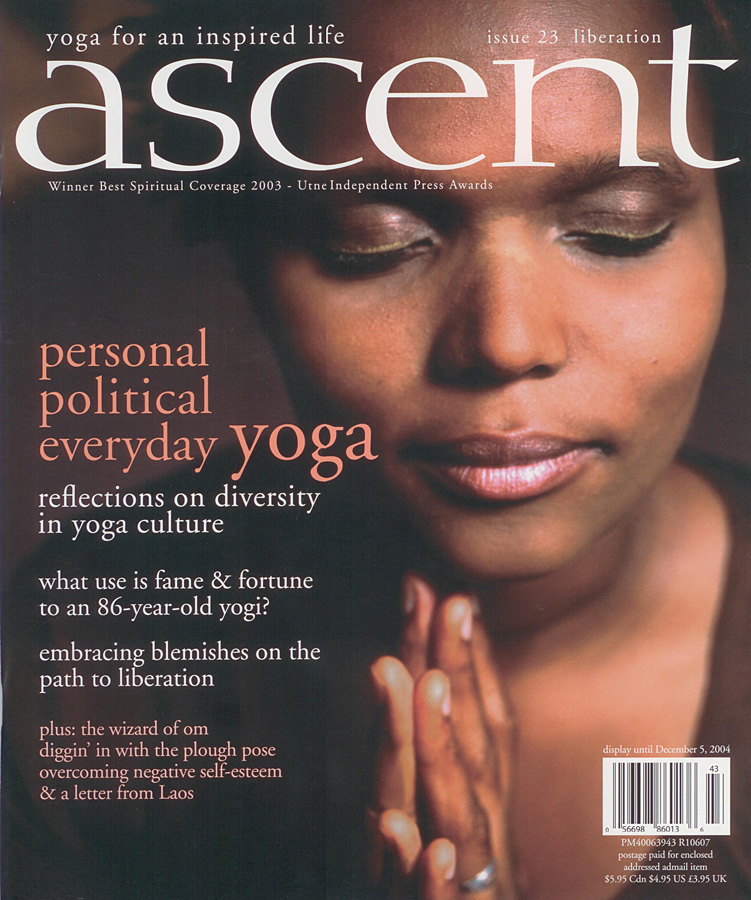

Full- and online version of interview in Ascent Magazine, nr. 23 fall 2004 by Marcus Boon.

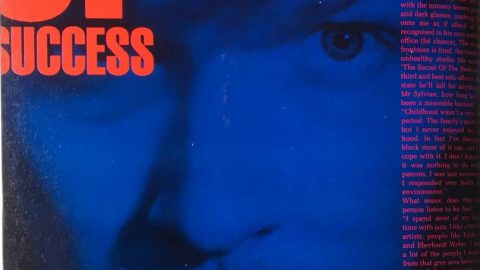

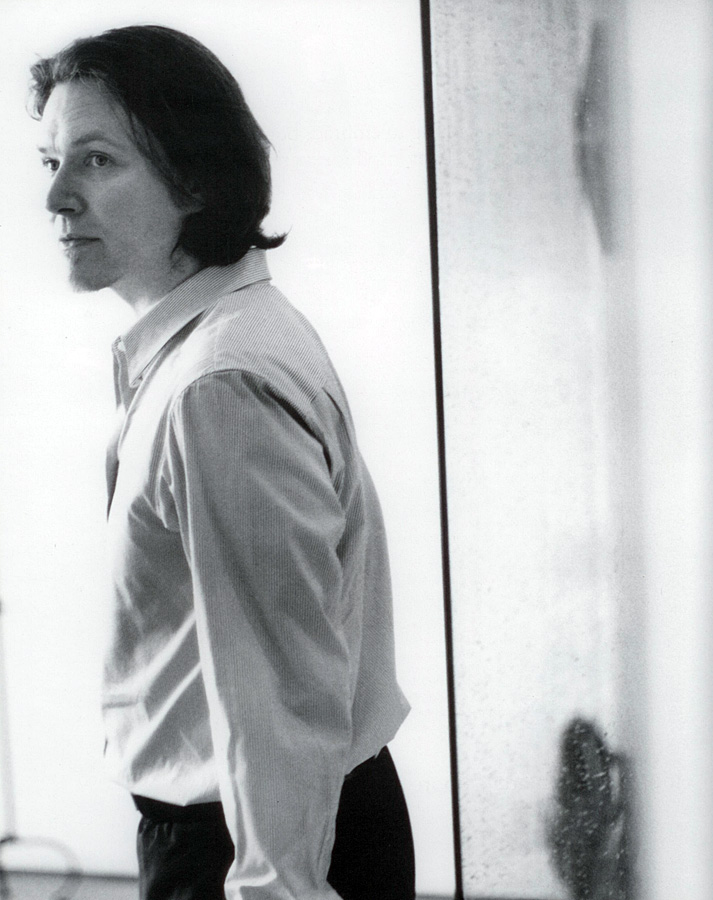

Aspirant & musician david sylvian, on learning to embrace both darkness & light into his experience of sadhana

Introduction:

My favourite David Sylvian song is called “Fire in the Forest.” Recorded in 2003 for his most recent CD, Blemish, the song, just a voice singing over a humming guitar drone, has a gentle intensity that pulled me through a winter spent riding around on public transportation in the suburbs of Toronto. Phrases like “there is always sunshinelbehind the grey skies/I will try to find it/yes I will try” heard on headphones again and again in snowy darkness somehow showed a fragile determination to transcend the ego’s limits. The track itself is all the more moving for its place at the end of a record full of dark songs about spiritual struggle.

Blemish is not a word normally associated with spiritual practice, yet the record reflects Sylvians growing and deepening experience of sadhana, first with Mother Mira, then Shree Ma, with whom Sylvian and his family lived in California in the mid-1990s, and in recent years with Mata Amritanandamayi or Amma, as she’s affectionately known.

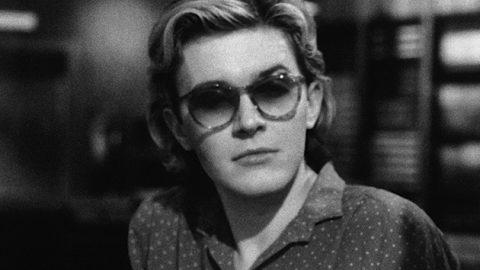

Sylvian grew up in a non-religious family in South London, England and formed the group Japan in 1974. The group went on to considerable success as glam/new romantic rockers, but broke up after releasing the marvelous Tin Drum (1981). Sylvian has pursued a solo career since, with early highlights including Brilliant Trees (1984) and Secrets of the Beehive (1987). A master of material describing an existential spiritual struggle – such as Tin Drum’s “Ghosts” with its chorus, “Just when I think I’m winning/when I’ve broken every door/the ghosts of my lifelblow wilder than before” – Sylvians songs have taken on an increasingly explicit spiritual form, reflecting his studies with various teachers after his move to America in the 1990s, where he still lives with his wife, Singer Ingrid Chavez, and children.

After the devotional lushness of 1999’s Dead Bees on a Cake, the austere, intense Blemish, with its stunning minimalist guitar work courtesy of Christian Fennesz and Derek Bailey, comes as a surprise. The surprise for me, however, is one of recognition, of having feelings, confusions and internal struggles that I could not find a way of articulating suddenly manifested, in gentle yet rigorous form.

One of Sylvian’s most remarkable songs, Secrets of the Beehive’s “Orpheus,” sings of the Greek legend, whose singing could charm animals, humans and gods alike. We think of music today as something disposable, as “pop,” as background music. Without hiding behind the rhetoric of “high art” or of any particular religious practice, Sylvian’s music points to that Orphic power of music, to reveal to ourselves what it means to be alive.

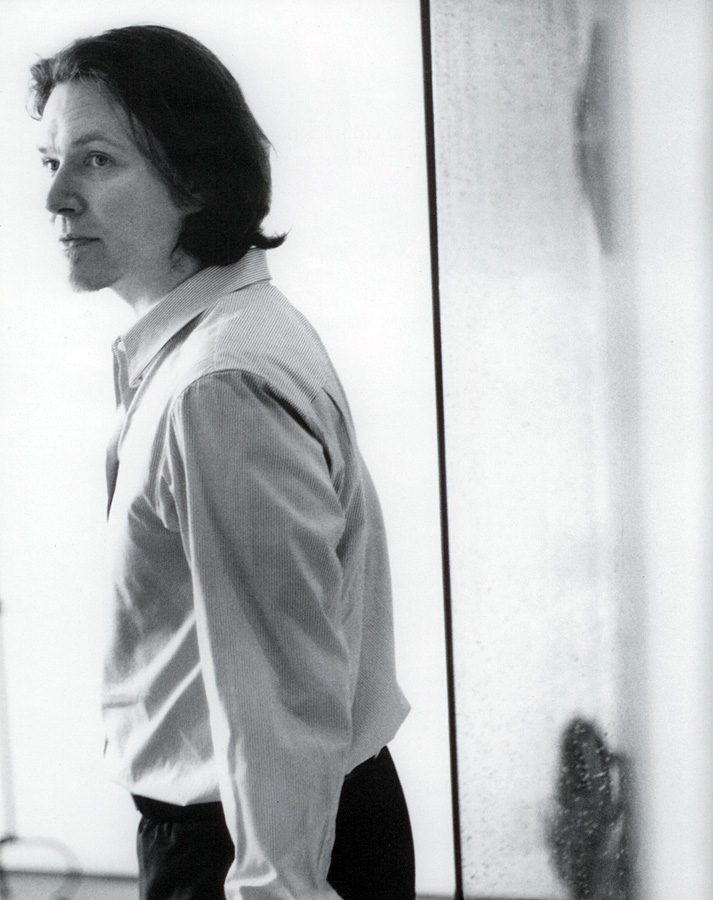

I met Sylvian in downtown Manhattan with his ten-year-old daughter, Amira. The singer still has the beauty of legend, but little of the ethereal quality that is habitually attributed to him. He speaks quietly, thoughtfully, precisely, while his daughter speaks on a cellphone to her mother, or lounges, reading, generously tolerating us. -MB

Interview by Marcus Boon

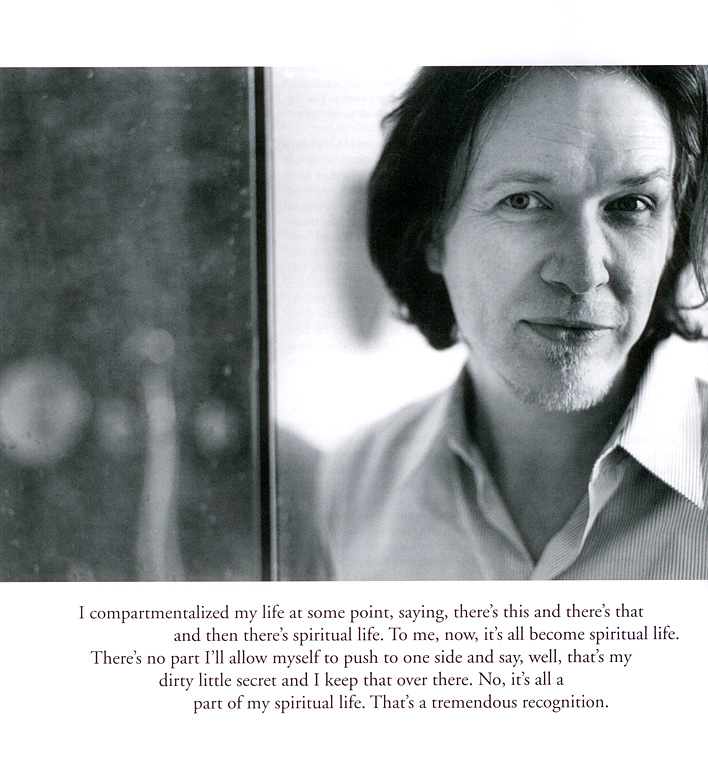

photographs by Darren Keith

Interview:

David Syivian I often feel that there’s a greater union between myself and my teacher when I’m not physically in their presence. There’s a whole other level of experience when I’m in their presence, but that sense of non-physical merging, of intimacy, is profound.

Marcus Boon It’s surprising that you can visit someone who’s been dead for 600 years and burst into tears in their presence. That’s how I felt at Hazra: Allaudin Sabri’s shrine in India. They say that he was so fierce in his lifetime that the only person who could come physically close to him was a musician, who would sit fifty feet away and play for him. And you can still feel that fierceness today!

DS That’s another element, isn’t it? The element of ferocity in the proximity of the guru. People talk about the experience of bliss, but the level of ferocity, the fire that one has to walk through, live through – that is also very intense. The degree of suffering increases as the experience of sadhana deepens, for me, because at first there’s less attachment to who one believes one is and it’s easier to let go of all the things that need to be let go of. As you move through different stages, the degree of fear increases because ultimately you’re getting to the root foundations of the ego, which are unshakable. And there is real fear because you see the death of the ego approaching, and if you let go of that, what is there?

As you have to face your fears in the presence of your guru, you witness other people going through their experiences. There’s often this perception, “Why do I have to live through this fear?

I’ll take on anybody else’s obstacles, but not this one!” [laughs]. It’s so pinpointperfect, it’s precision-made, this laser-like intensity focusing on just what needs to be focused on. Once you move beyond a given level of fear, apprehension, there’s an enormous release and a whole new world of possibility seems to open up. You live and breathe that for a while until you come up against that next obstacle.

MB A lot of people like to think that a spiritual narrative consists of going from darkness and suffeling to peace and equanimity, but I think of your music, and in particular of Blemish, which is so much darker than the records that came before. It’s still a record about sadhana .

DS It’s darker than ever! But going through that experience of darkness at this point in my life is very different than before. First of all, there is a certain amount of objectivity, of being able to step back and say, all of this is just par for the course, it’s just part of the learning process, whatever comes out of this is just to strengthen me and help me to burn off whatever needs to be cleared away so that I can see things clearly.

And a lot of things that I couldn’t face in my life I could face in the studio environment. I closed that door and started working and opened myself to whatever came through. And often it was very negative emotions. And I thought, well, I’ll just look straight at them, and more than that, I’ll take them even further than I feel them in my daily life, because I wanted to go as far with them as I possibly could. I felt very safe doing that. I felt that there was a strength inside of me that would allow me to pull back at the end of the day and be able to do away with those emotions. So I was pushing myself deeper and deeper into the negativity of the experience, wanting to know what that felt like, how does that surface and how do you give that a voice? It was a way of experiencing those experiences and giving them a new vocabulary that was pertinent for now.

MB Now, as in our time?

DS Yes. I was also feeling that all the familiar forms of popular song were no longer doing it for me. Even those evergreen artists that you go back to time and time again weren’t moving me anymore. The form had lost its potency; it had been exhausted. I was beginning to feel: what next, what do you do? And I felt that I personally had to find a new form for what I was experiencing. I feel it’s true of other arts, too: now is an important time to find vocabularies that are pertinent to our time.

Everything becomes a commodity. We’re told that if we understand some one’s taste in how they decorate their home, then we can probably guess what kind of music will go with that environment. Everything gets tied together in packages so we can all have what’s known as “good taste.” We can dress well, we have good taste in our cultural environment, we can participate in it but without any commitment, no going out on a limb, always tapping into something that’s termed “classic,” whether it’s a couch or a Marvin Gaye record.

But when we find something that challenges all of that in the culture, that’s when we discover who we are, and our response isn’t preconditioned. We don’t have the benefit of reading a review of this experience prior to having it. We have to comprehend it on our own terms, ask: “Why did I feel so irritated when I was provoked in that way?” I want to have that kind of experience. The one that isn’t scripted. The one that will throw you into the deep end of an experience and you just have to work it out for yourself. There is no right or wrong response, only your true response. And that’s what I try to find in my work, that true response. It doesn’t necessarily make it that comfortable an experience to listen to, but that’s not the issue here. It’s just trying to find a means to grapple with what it means to be alive in the here and now, trying to find a vocabulary for it, trying to press the right buttons in me, and hopefully that will communicate to others.

MB When you think of musicians who’ve become involved in sadhana, they often take on the costumery that comes with sadhana, but you seem to have made a conscious decision against doing that.

DS It’s just not an outfit that feels comfortable to wear. You try everything at some point or another. When I was with Shree Ma we went through that, as a family, supporting and performing with her, but it didn’t feel right.

MB Have you done bhajans?

DS I haven’t recorded them, but we’ve sung them, obviously. I’m very familiar with the form. But there’s a certain resistance to that as a musician, an artist. I feel that I’m a very fallible person, I have powerfully conflicting emotions, and I don’t want to give the false impression that all is right in my world.

On one level, the world has a beautiful simplicity and clarity to it; on another level it’s only got far more complicated, with an increased degree of suffering. Sometimes I may only want to focus on the blissful elements of Divine awareness, maybe within an entire project or just within one piece of music. Or maybe it lies behind everything I do already It’s hard to say I don’t analyze what I do to that degree. But I can’t do away with all the questions I have about what it means to be alive in the here and now, all the troubles and emotional conflicts, the love and hate that live side by side.

I don’t believe I ever feel only love except possibly in the lap of Amma. Outside of that beautiful place, love is accompanied by a whole complexity of emotions, including its mirror opposite. I want my work to have that complexity, because the best work is the kind of material that, no matter what frame of mind you come to it with, you can still see yourself mirrored in it.

The great failure of so-called “spiritual music” that we’re surrounded by in this culture is that it’s a music that tries to placate, it tries to insist that you be peaceful and filled with love. Well, nothing could irritate me more than being surrounded by a work of art at any level that insists I feel something. I would rather my work embody all the possibilities and let people find themselves within it, and find a release.

That’s the best that I can do. I wouldn’t want to give the impression of an ivory tower existence where nothing seems to touch you anymore, that somehow you can ride over all these obstacles because you’ve found a greater inner peace.

MB That’s the problem of New Age music, and why so many people are so resistant to the idea of spiritual practice, or music that addresses spiritual issues.

DS Yes, but it’s funny – we spoke earlier about spiritual music, and the first name that came up was John Coltrane. And that’s the antithesis of everything we think of culturally as spiritual music. But it’s right there, the fire of purification, of suffering, of bliss. It’s all there, embodied, and you can tap into that work on any of those fundamental levels and experience it in a beautiful and profound way That’s the beauty and strength of a work that reflects all that we are and potentially can be. Maybe it’s too much to strive for and maybe you’re guaranteed to fail 99.9 percent of the time. But it’s definitely a goal worth aspiring to.

MB Your own sadhana is involved in very complex spiritual traditions, but the terms in which you describe spiritual struggle in your music, aside from a song like “Krishna Blue” on Dead Bees on a Cake, avoid direct reference to these traditions and practices. Why do you think that is?

DS I don’t want to fall into a stereotypical response to my relationship to the Divine. I don’t want it to feel too comfortable in my own work, as a writer. Writing a piece like “Krishna Blue” – that was during a period of the enormous romance of the relationship with the guru, which is lovely, and it’s still present in my life. But now I want to deal with the complexity.

In a sense, the guru romances you to begin, you kind of get an easy ride so that you can just experience all the profound love that is there, without the discolouration of your own ego. And once you have been led in so far, you begin to have experiences that are more profound but far more difficult to undergo. I don’t want to fall back on the romance of the journey. What is more intriguing is the reality of the journey because the reality is so much more amazing than simply the romance. The reality of the journey encompasses so much, and there’s no separation from it in any aspect of life. Not one aspect, no matter what one is doing. That’s an incredible thought.

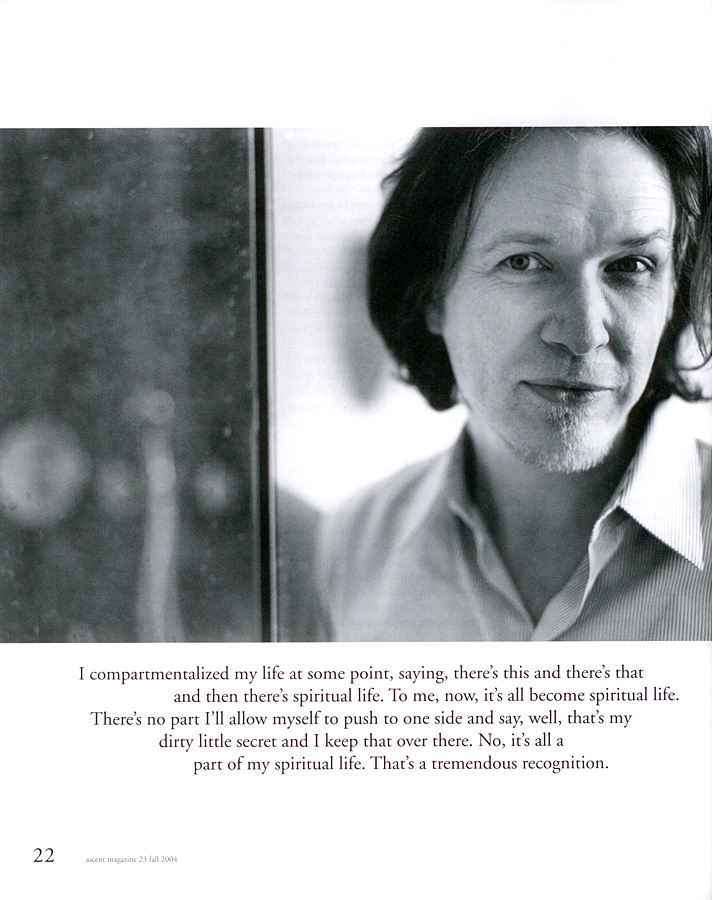

I compartmentalized my life at some point, saying, there’s this and there’s that and then there’s spiritual life. To me, now, it’s all become spiritual life. Compartmentalizing seems to be born out of what one perceives to be the good and bad in one’s self, the different faces we show to ourselves, and ultimately the need to tell a story about who we are that excludes activities that don’t quite fit in with the story, which we may enact occasionally and then bury when they’re no longer necessary. There’s no part I’ll allow myself to push to one side and say, well, that’s my dirty little secret and I keep that over there. No, it’s all a part of my spiritual life. That’s a tremendous recognition. Years and years of analysis couldn’t have brought me to this point in time, to bring all of these separate elements together and embrace them as one.

MB It’s so hard to know what to do with the outbursts, the things that one would like to be exceptions to the nice pure spiritual system. I love that title, Blemish, Jor that reason. It’s the hardest thing to face up to.

DS It really is. To me the notion of telling a story about who one is, while it facilitates a sense of mental well-being and coherence to one’s life journey, is basically a lie. It’s so well edited that it can’t possibly embrace who we really are, and of course who we really are is beyond all of that. So I’ve tried to let go of the notion of the story. In fact, now that there are all these different component parts of who I am, there is no conceivable story that can hold it. There are moments that shine with clarity and beauty, and then there are these darker elements that are extremely dark. What am I going to do with them? All I can say is that that’s Divine too, and I now have to bring them in and embrace them as who I am, and they’re part of me until whenever, until the next stage.

Marcus Boon teaches contemporary literature at York University in Toronto. He writes abour musie for The Wire, and studies ashtanga yoga and Tibetan Buddhism. His work can be found at Hungry Ghost .

Thanks to Eddie Stern, Robert Moses and Kristin Leigh for their generous help with this article.

Online version:

excerpted from the print magazine

My favorite David Sylvian song is called Fire in the Forest. Recorded in 2003 for his most recent CD, Blemish, the song, just a voice singing over a humming guitar drone, has a gentle intensity that pulled me through a winter spent riding around on public transportation in the suburbs of Toronto. Phrases like there is always sunshine/behind the grey skies/ I will try to find it/ yes I will try heard on headphones again and again in snowy darkness somehow showed a fragile determination to transcend the ego’s limits. The track itself is all the more moving for its place at the end of a record full of dark songs about spiritual struggle.

Blemish is not a word normally associated with spiritual practice, yet the record reflects Sylvian’s growing and deepening experience of sadhana, first with Mother Mira, then Shree Ma, with whom Sylvian and his family lived in California in the mid-1990s, and in recent years with Mata Amritanandamayi or Ammachi, as she?s affectionately known. Sylvian grew up in a non-religious family in South London, England and formed the group Japan in 1974. The group went on to considerable success as glam/new romantic rockers, but broke up after releasing the

marvelous Tin Drum (1981). Sylvian has pursued a solo career since. A master of material describing an existential spiritual struggle – such as Tin Drums – Ghosts- with its chorus, ‘Just when I think I’m winning/ when I’ve broken every door/ the ghosts of my life/ blow wilder than before’ . Sylvian’s songs have taken on an increasingly explicit spiritual form after his move to America in the 1990s, where he still lives with his wife, singer Ingrid Chavez, and their children.

I met Sylvian in downtown Manhattan with his ten-year-old daughter, Amira. He speaks quietly, thoughtfully, precisely, while his daughter talks on a cellphone to her mother, or lounges, reading, generously tolerating us.

Marcus Boon A lot of people like to think that a spiritual narrative consists in going from darkness and suffering to peace and equanimity, but I think of your music, and in particular of Blemish, which is so much darker than the records that came before. It’s still a record about sadhana.

David Sylvian It’s darker than ever! But going through that experience of darkness at this point in my life was very different to before. First of all, there was a certain amount of objectivity, of being able to step back and say, all of this is just par for the course, it?s just part of the learning process, whatever comes out of this is just to strengthen me and help me to burn off whatever needs to be cleared away so that I can see things clearly.

And a lot of things that I couldn’t face in my life I could face in the studio environment. I would close that door and start working and open myself to whatever came through. And often it was very negative emotions. And I thought, well, I’ll just look straight at them, and more than that, I’ll take them even further than I feel them in my daily life, because I wanted to go as far with them as I possibly could. I felt very safe doing that. I felt that there was a strength inside of me that would allow me to pull back at the end of the day and be able to do away with those emotions. So I was pushing myself deeper and deeper into the negativity of the experience, wanting to know what that felt like, how does that surface and how do you give that a voice? It was a way of experiencing those experiences and giving them a new vocabulary that was pertinent for now.

MB Now, as in our time?

DS Yes. I was also feeling that all the familiar forms of popular song were no longer doing it for me. Even those evergreen artists that you go

back to time and time again weren?t moving me anymore. The form had lost its potency; it had been exhausted. I was beginning to feel: what next, what do you do? And I felt that I personally had to find a new form for what I was experiencing. I feel it?s true of other arts, too: now is an important time to find vocabularies that are pertinent to our time.

Everything becomes a commodity. We’re told that if we understand someone?s taste in how they decorate their home, then we can probably guess what kind of music will go with that environment. Everything gets tied together in packages so we can all have what’s known as ‘good taste.’ We can dress well, we have good taste in our cultural environment, we can participate in it but without any commitment, no going out on a limb, always tapping into something that’s termed ‘classic,’ whether it’s a couch or a Marvin Gaye record.

But when we find something that challenges all of that in the culture, that’s when we discover who we are, and our response isn’t preconditioned. We don’t have the benefit of reading a review of this experience prior to having it. We have to comprehend it on our own terms, ask: ‘Why did I feel so irritated when I was provoked in that way?’ I want to have that kind of experience. The one that isn’t scripted. The one that will throw you into the deep end of an experience and you just have to work it out for yourself. There is no right or wrong response, only your true response. And that’s what I try to find in my work, that true response. It doesn’t necessarily make it that comfortable an experience to listen to, but that?s not the issue here.

It’s just trying to find a means to grapple with what it means to be alive in the here and now, trying to find a vocabulary for it, trying to press the right buttons in me, and hopefully that will communicate to others.