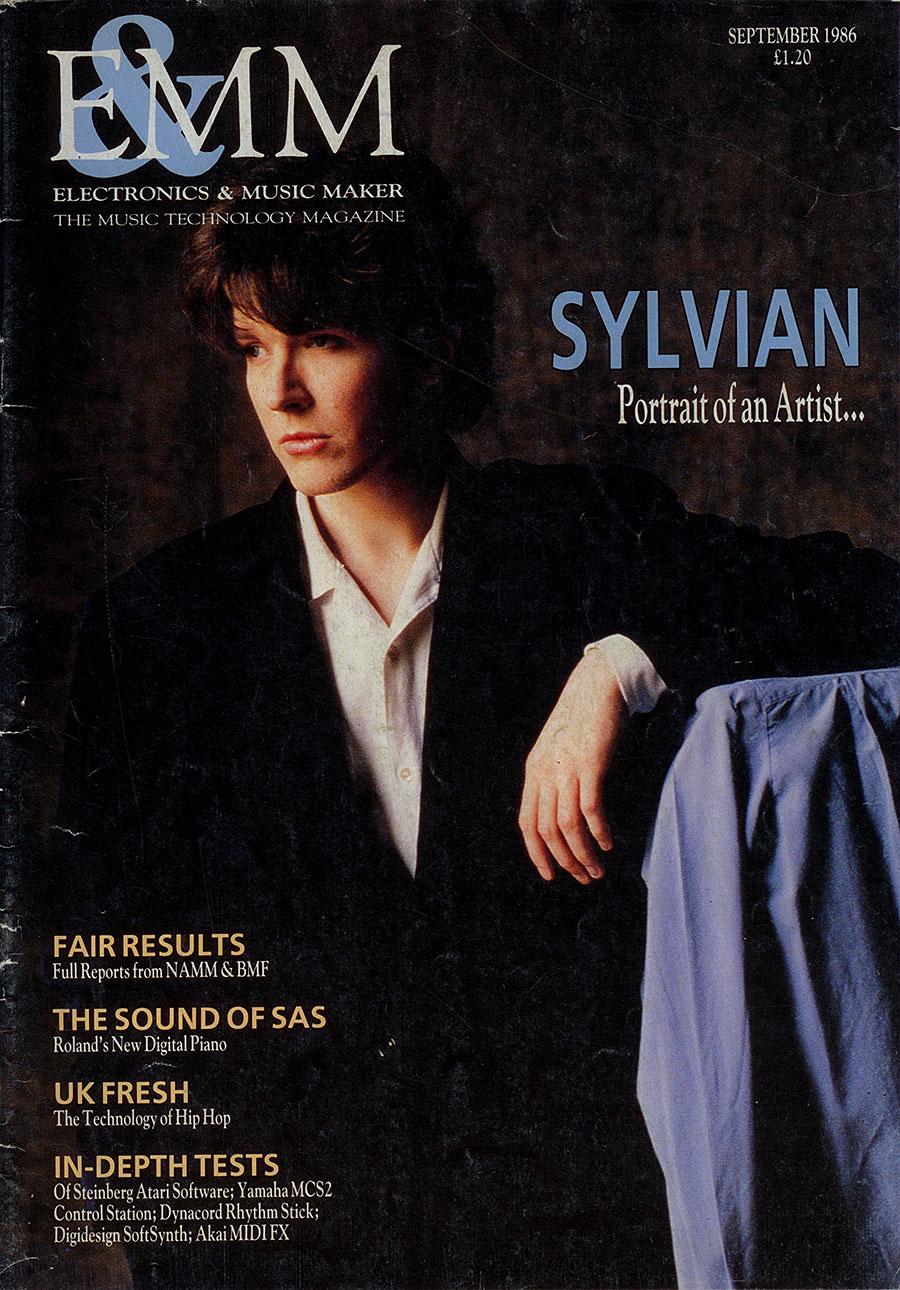

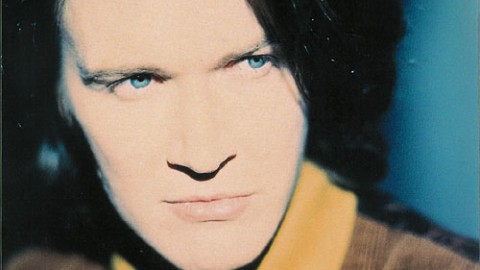

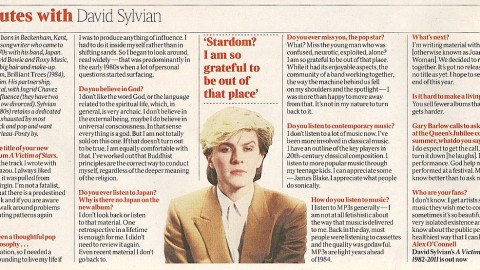

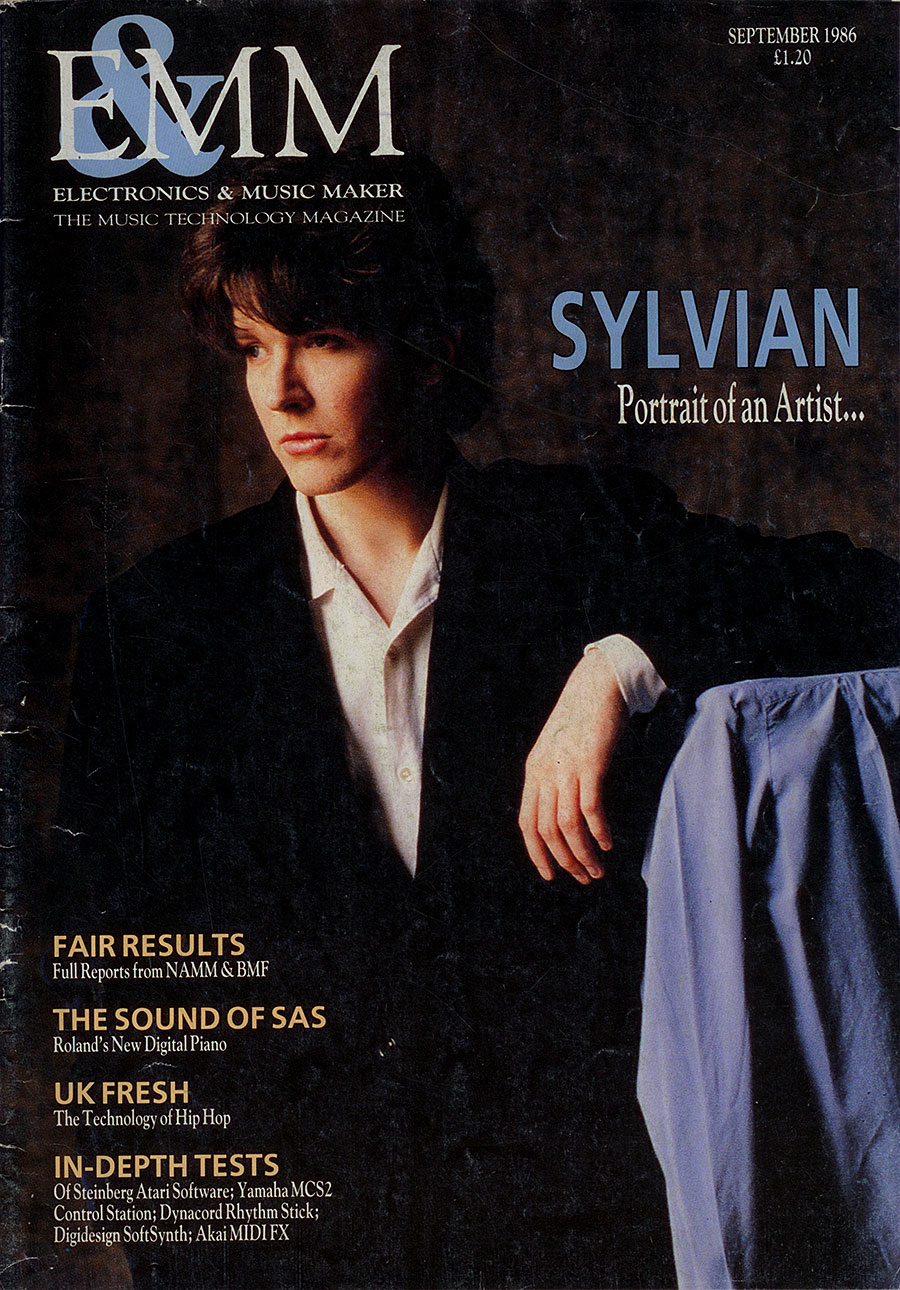

Interview by Tim Goodyer. Fotography by Martin Goddard. (E&MM, Sept. 1986)

As well as gaining artistic credibility since leaving Japan. David Sylvian has inspired musicians with his ability to fuse traditional ethnic and hi-tech elements into a moving and unique brand of music. A new single, ‘Taking the Veil’, is the prelude to a double album that explores both Sylvian’s songwriting and his growing interest in improvised and ambient music.

FEW PEOPLE WOULD DISPUTE the significance of David Sylvian’s Japan. During a long but only fitfully successful career, the band exerted an influence that spread from pop music to teenage girls’ (not to mention boys’) make-up, and left an indelible mark on contemporary pop and rock instrumentation.

When Japan were at the peak of their influence and ability, the innovative fretless bass-playing of Mick Karn spawned hordes of imitators, while Steve Jansen took conventional pop drumming into new areas of complex percussion arrangements. Meanwhile, the conventional role of ‘keyboard player’ underwent a subtle metamorphosis, as Richard Barbieri became one of the first of a new generation of synthesiser ‘programmers’; and singer, songwriter and face David Sylvian fused elements of artistic moodiness and pop glamour with an undeniably mature and sensitive songwriting style.

Japan began life back in 1978, asa rebellious group of London schoolboys with designs on fame and fortune no different from those of a thousand other hopefuls.

At the start they borrowed liberally from America’s New York Dolls, and produced two albums on the PRT label, Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives, with the assistance of guitarist Rob Dean. Both albums overflowed with raucous guitars, ‘controversial’ lyrics and cliched heavy rock production touches, and both albums are now generally disowned by members of the band -Sylvian himself refers to them simply as ‘mistakes’.

A third album, Quiet Life, the band’s only release on the Hansa label, marked a complete change in both image and musical direction. A catchy, moderately successful single of the same name relied heavily on a simple sequence supporting a deranged bass line and a vocal rich in stolen Bryan Ferry inflexions, while the remainder of the album displayed a sensitive side of Sylvian that had previously been obscured by the bravado of distorted images and guitars. Quiet Life got to number 19 in the charts, stayed around for nine weeks, and gave Japan a new lease of life.

‘We got the first album completely wrong, so we did another and that was wrong as well’, Sylvian recalls. ‘We were going to split up after that. We didn’t work for six months to a year and then I started writing again -not from pressure, but because I felt the need to.’

By 1980, Japan were hot property and signed a contract with Virgin. Gentlemen Take Polaroids further established the direction indicated by Quiet Life, with an air of mystique and sophistication surrounding its music. Influences, rarely hidden by a band keen to exhibit a cosmopolitan background, spanned the works of Erik Satie (‘Nightporter’), David Bowie circa Low (‘Burning Bridges’), and Yellow Magic Orchestra, whose keyboard player Ryuichi Sakamoto co-wrote the decidedly Oriental-sounding ‘Taking Islands in Africa‘.

Just one year later, the final Japan studio album was released. Tin Drum took yet another musical step forward, as a new approach to song arrangements saw the band having a greater say on the finished product, Jansen and Karn forming a shaky but startlingly original rhythm section, and Barbieri crafting some strikingly unelectronic-sounding textures. The album also affirmed Sylvian’s fascination with Japanese culture, philosophy and music.

But the strain that had already seen the departure of Dean took its toll of the other members of Japan, and only a farewell tour steeped in sentiment and an accompanying live album stood between the band and the end of their career together.

Five years later, Sylvian assumes some personal responsibility for the split. ‘When Japan split up I felt responsible to the others because they were sitting around doing nothing for most of the year, waiting for me to write enough material to go in the studio and tour afterwards. And, as I didn’t like touring, I’d limit the length of tours as well.

‘Things did build up on me when we moved from Hansa to Virgin. Normally I take longer to write material and I felt that from that point onwards I was fighting to keep up. Once I’d finished Polaroids I was struggling to write Tin Drum, after which I didn’t work for a year. I got myself back together with a balance within myself where the writing came naturally again.

But it wasn’t until three years after Tin Drum that Brilliant Trees was released. Sylvian the reluctant pop idol had faded, to be replaced by Sylvian the credible artist. His first solo venture was anything but solo -he had surrounded himself with respected names like ethnic trumpet player Jon Hassell, jazz musician Mark Isham and Can founder member Holger Czukay, and merged their talents with those of old campaigners Jansen and Barbieri. The mixture, a culture clash of styles and temperaments, created one of the best albums of 1984- a contradiction of jazzy, instrumental improvisations, electronic experiments, and Sylvian’s familiar vocal style.

A short video and sound track, Steel Cathedrals, and an EP of instrumental pieces, Words with the Shaman, have barely served as fillers during the overlong pause between Brilliant Trees and the forthcoming Sylvian LP, Gone to Earth.

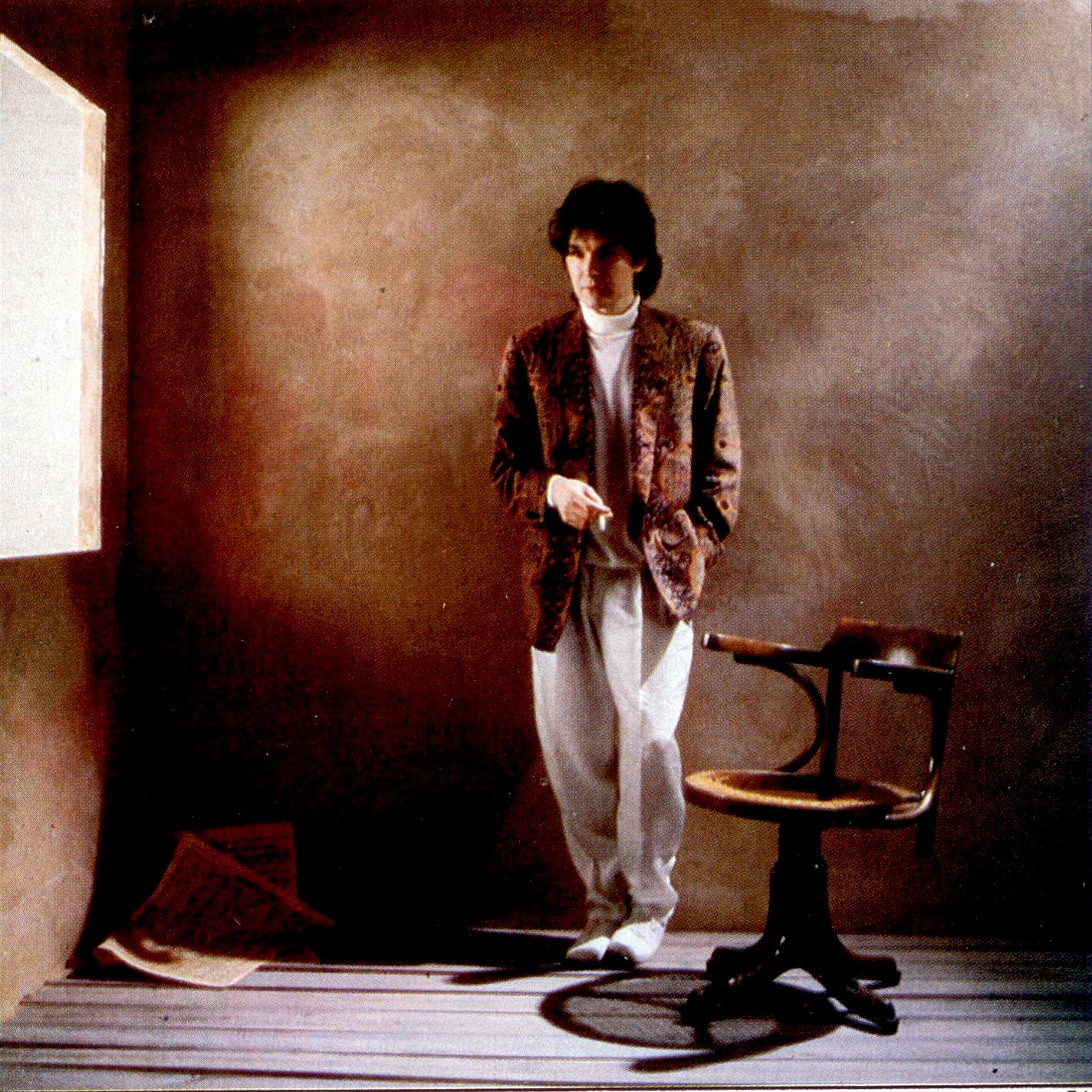

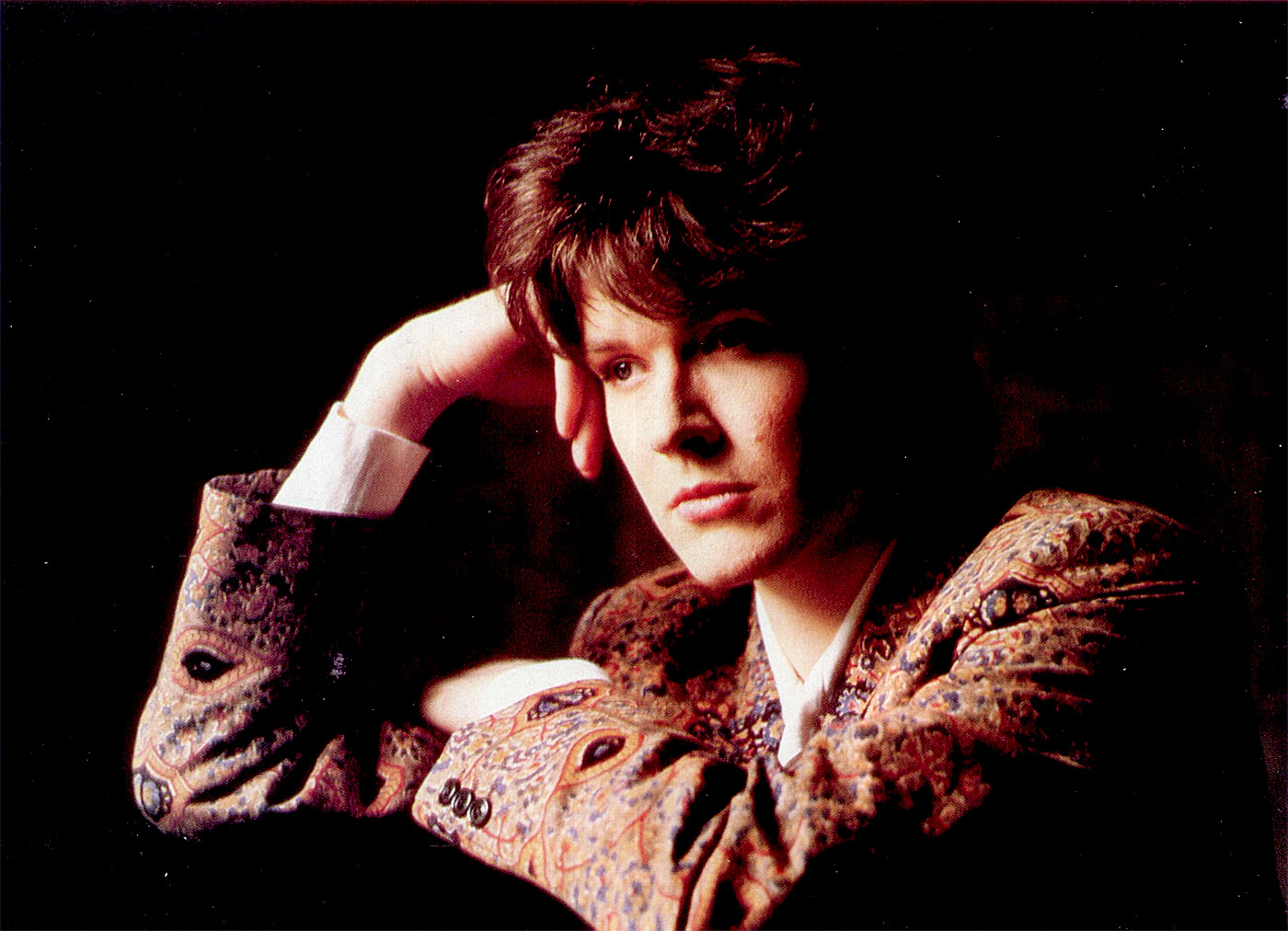

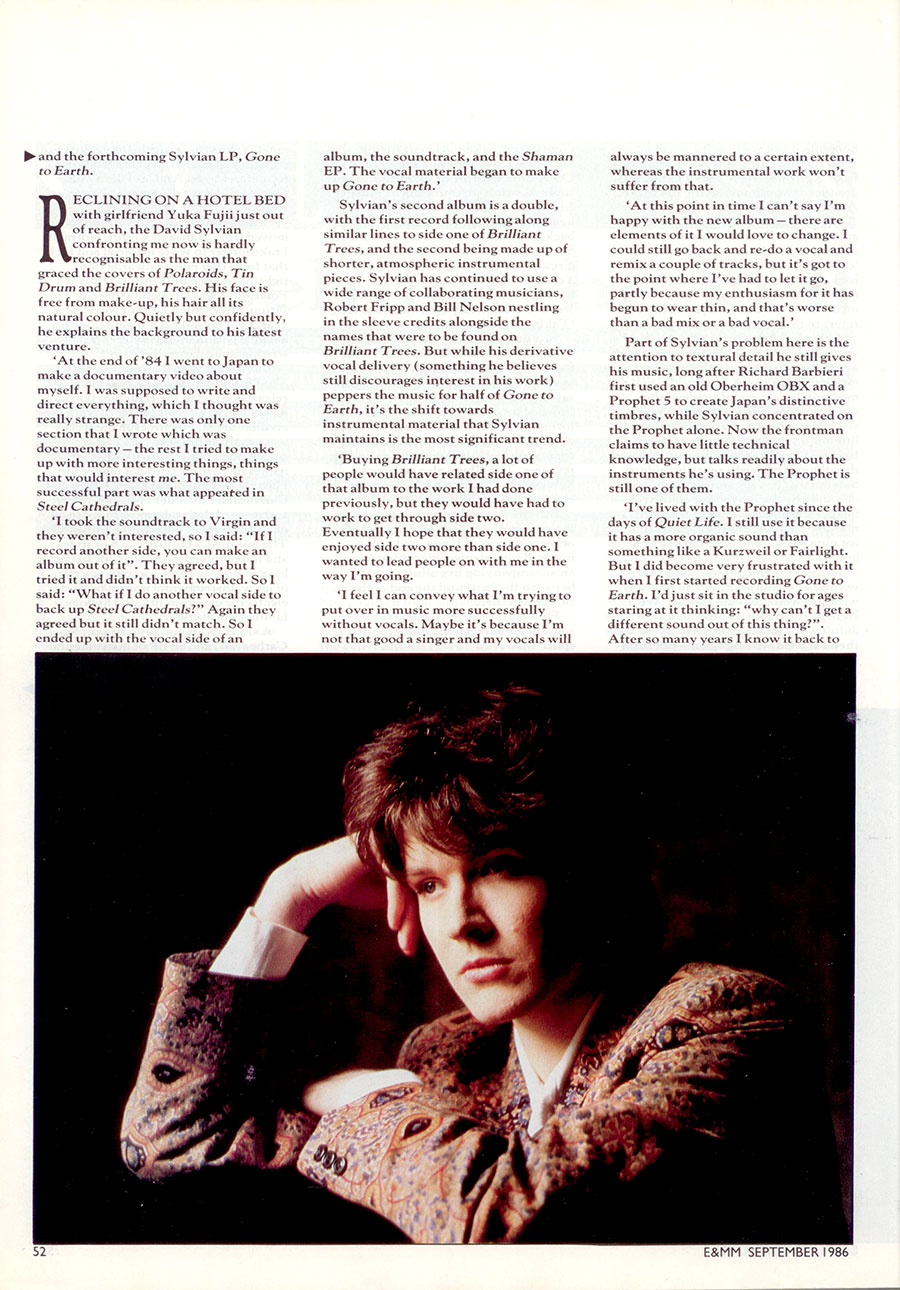

RECLINING ON A HOTEL BED with girlfriend Yuka Fujii just out of reach, the David Sylvian confronting me now is hardly recognisable as the man that graced the covers of Polaroids, Tin Drum and Brilliant Trees. His face is free from make-up, his hair all its natural colour. Quietly but confidently, he explains the background to his latest venture.

‘At the end of ’84 I went to Japan to make a documentary video about myself. I was supposed to write and direct everything, which I thought was really strange. There was only one section that I wrote which was documentary- the rest I tried to make up with more interesting things, things that would interest me. The most successful part was what appeared in Steel Cathedrals.

I took the sound track to Virgin and they weren’t interested, so I said: “If I record another side, you can make an album out of it”. They agreed, but I tried it and didn’t think it worked. So I said: “What if I do another vocal side to back up Steel Cathedrals?” Again they agreed but it still didn’t match. So I ended up with the vocal side of an album, the sound track, and the Shaman EP. The vocal material began to make up Gone to Earth.’

Sylvian’s second album is a double, with the first record following along similar lines to side one of Brilliant Trees, and the second being made up of shorter, atmospheric instrumental pieces. Sylvian has continued to use a wide range of collaborating musicians, Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson nestling in the sleeve credits alongside the names that were to be found on Brilliant Trees. But while his derivative vocal delivery (something he believes still discourages interest in his work) peppers the music for half of Gone to Earth, it’s the shift towards instrumental material that Sylvian maintains is the most significant trend.

Buying Brilliant Trees, a lot of people would have related side one of that album to the work I had done previously, but they would have had to work to get through side two.

Eventually I hope that they would have enjoyed side two more than side one. I wanted to lead people on with me in the way I’m going.

‘I feel I can convey what I’m trying to put over in music more successfully without vocals. Maybe it’s because I’m not that good a singer and my vocals will always be mannered to a certain extent, whereas the instrumental work won’t suffer from that.

‘At this point in time I can’t say I’m happy with the new album -there are elements of it I would love to change. I could still go back and re-do a vocal and remix a couple of tracks, but it’s got to the point where I’ve had to let it go, partly because my enthusiasm for it has begun to wear thin, and that’s worse than a bad mix or a bad vocal.

‘Part of Sylvian’s problem here is the attention to textural detail he still gives his music, long after Richard Barbieri first used an old Oberheim OBX and a Prophet 5 to create Japan’s distinctive timbres, while Sylvian concentrated on the Prophet alone. Now the frontman claims to have little technical knowledge, but talks readily about the instruments he’s using. The Prophet is still one of them.

‘I’ve lived with the Prophet since the days of Quiet Life. I still use it because it has a more organic sound than something like a Kurzweil or Fairlight. But I did become very frustrated with it when I first started recording Gone to Earth. I’d just sit in the studio for ages staring at it thinking: “why can’t I get a different sound out of this thing?”.

After so many years I know it back to front -it’s very limiting now.

‘It was a really good experience working on Tin Drum, because Rich and I would sit and sweat it out all day, finding the right sound for one phrase. When we thought it was perfect, Steve (Nye, producer) would transform it into something else. A lot of the sounds that I hear on Tin Drum I couldn’t possibly get back on the Prophet or the OBX. I think a lot of that comes down to Steve’s engineering and production – he’s got a very subtle approach.

‘I don’t think that the quality of the DX7 is the same as something like the Prophet. The percussive sound of the Prophet is much softer, much warmer, -there’s a depth to it. I find the DX sounds too contemporary -they sound like they should appear on a pop record, and that doesn’t interest me.’

Like so many, Sylvian finds the programming habits enforced by multi-function controls and small panel displays an almost insurmountable handicap, and is quick to point the finger of blame at modern synth design for the current fascination with preset sounds.

‘I don’t think most people try to make their own character out of synthesisers. Because a guitar is such a musical instrument, you have to make an individual character out of the sound, not just out of the style of playing. I think you should approach the synthesiser with the same idea -to create something very personal instead of creating something that just sounds like a synthesiser.

‘If I use a synthesiser and I recognise the origin of a sound, then I’m loath to record it. I have to try and disguise it. You shouldn’t be aware of what you’re hearing- it should be more abstract.

‘I think technology will catch up and become a lot simpler. It has to for music to become more spontaneous -it’s probably the reason why a lot of synthesiser music isn’t spontaneous, why it’s mapped out the way it is with arranged pieces of music.

‘Synthesisers should become so flexible that they can be used in any kind of improvisational situation. At the moment synthesisers are designed mainly for inventive recording purposes -the ones that are put together for live conditions are really used just to capture things that you’ve done in the studio. I don’t think anything’s really being used in a live context creatively. That’s the direction that people who put the things together should be working in.

‘If it works under live conditions, it will work in the studio. If you get very close to a sound in live performance, then to modify that sound while it’s actually being played is an interesting thing to listen to. If it’s not too far away from what you’re looking for, the modification becomes musical in itself.

‘Something else that’s needed is the ability to sample something being performed on the stage at the time the improvisation is going on, and then start playing that back. Someone like Hassell works with an AMS -he plays something and samples a piece of it. Then he’ll improvise over the top of that to extend the idea. In that way a solo performer can conjure up a dense atmosphere of layers.’

IN STARK CONTRAST to the approach adopted by Japan, improvisation has now become a major part of Sylvian’ s music, hence his interest in getting technology to become more involved in less structUred, less formalised ways of making music.

‘When I became interested in painting, Yuka and I discussed how close music comes to the purity of line of a painter, the inspiration of just one line. When you see the painting you can feel the presence of the painter because of that purity. We felt the only thing that could come close was improvisation, so I started listening to jazz and a lot of the influences came from there.’

The creation of musical environments and atmospheres is the direction Sylvian feels synthesiser improvisation could profitably take. He remains unimpressed by the way older, more established keyboardists have improvised with synths, and feels the generations now growing up with technology are more likely envoys of what could be a new age of musical exploration.

‘It would be interesting to have younger people improvising with synthesisers under live conditions. I think it would be stimulating for an audience and for the performer, without being self-indulgent. It can be an uplifting experience just as much as any structUrally-based classical music can. It can have the same quality about it because it turns you inwards to reflect on yourself, and I think that’s an important quality of all art.

‘A lot of young people aren’t technically proficient and so can’t get out of their instruments what jazz musicians can. That’s where I think synthesisers come in, because if you improvise you can explore. Older jazz people that use synthesisers use presets and they sound awful in jazz. It’s like using a rhythm box in jazz- it just doesn’t work.

‘It’s really open to the younger people because sound is more important to them than it was to the generation before. I think that should open new doors and technology can help. It’s like computer games -they’re for the younger generation, they belong to them. It’s just a case of whether they can be creative about using them, because it’s so easy to fall into using a formula.’

It’s to avoid falling into just such a trap that Sylvian has stuck to his policy of using the external influence of guest musicians, each of which brings his own, unexpected contribution to the end product. And none of Sylvian’s recent collaborators has done more to introduce an element of chance than German-based Holger Czukay.

‘When Holger came to London to work on Shaman, he brought a handful of cassettes he’d taken from the radio’, recalls Sylvian. ‘He’d suggest a cassette for what we were listening to, and say we’d leave the cassette running while we recorded. There are things that would fall into place, and anything that didn’t would be spooled back in to the right place. I find that a very interesting way of working -leaving things to chance.

‘That’s the way he works with the dictaphone as well. On ‘Pulling Punches’ ( opener on Brilliant Trees ) there are a lot of brass things played on the dictaphone which just happened. We ran through the track and he played the tape, and they all fell into the places they are on the finished piece. That kind of thing is an improvisation of tape which I’d never heard of before I worked with Holger.

‘I like the way Holger works with radio too, though I don’t use it myself so much. I used a little bit on ‘Taking the Veil’ (the new single) but it’s really mixed in with the guitar. When we did the album I was playing guitar and harmonium and Holger was producing, and at the same time he was running pieces of short-wave radio through the speakers. We were hearing it, and it was being recorded at the same time as the piano and the guitar. That was interesting because we’d respond to what we were hearing. We might take all the radio out in the end, but it made a difference to what we were playing at the time. I like the idea of not knowing what’s going to happen.

‘I began to feel very stifled in Japan: I wanted to do something more spontaneous, where you did very little to actually impose yourself onto a piece of music. It’s worked in painting for ages but it hasn’t been done in music so much.

‘To try to create music that almost creates itself is something which I tried with Holger in Cologne. We tried not to play or to play as little as we could, and if we were playing, to play something as non-descript as possible. We put it all on tape and things would be recycled until eventually music would be playing that we weren’t performing at all. We’d stopped playing and we were just looping things that were going on. What I heard was a very organic piece of music. Like landscape music, it would conjure up scenes in mind very vividly, but it wouldn’t impose itself on you. It would enhance your own thought processes instead of taking over the atmosphere of the room.

‘I think that’s got to be the function of music more and more in the future: to enhance rather than change. It’s the same as painting does, and I think music should adapt to that more and more.’

YET NO MATTER HOW much David Sylvian experiments with his music, the popular music press will continue to focus attention – as they invariably do -on his personality, and the way it manifests itself in his lyrics.

On Gone to Earth, those lyrics are more introspective, more self-searching than ever. And while that introspection may deter some listeners from getting closer to Sylvian’s work, the man himself sees it as an inevitable consequence of his intimacy with Japanese culture and its philosophy of self-discovery.

‘You definitely learn through what you write-if you don’t then there’s something wrong. It has to have a very human quality about it, even if it’s as stylised as Japan -it has to relate to people on a very personal level. Without that I don’t think people relate to music over a long period of time.

‘When I wrote ‘Ghosts’ it was after a very dark period I went through.l wrote the piece and thought: “Yes, that sums it up very well”. But after I recorded it, after it had been a hit, I went through an even darker period and I thought: “This is what it’s really about”. I hadn’t experienced it the way I thought I had, and yet the song summed up that period very well. It was a very bleak time -every time you thought you were getting somewhere, something would stand in your way.

‘When I wrote Brilliant Trees I was becoming more and more interested in the spiritual life. I hadn’t come across the Kabbala and the Tree of Life, but I was on the brink of discovering it. When I did I found that’s what ‘Brilliant Trees‘ related to, but I had no concept of that at the time. I’ve found it happens quite a lot, even when I first started writing. I think you anticipate your next stage of changing, self- consciously.’

Once inspired to writing by travelling, Sylvian has become self-sufficient as a result of his learning, and has scarcely travelled anywhere at all in the last 18 months.

‘I’m obviously inspired by books, by paintings, films, whatever, but they draw on a source that’s already within me. I’m very interested in myself in the way I’m growing and where my mind is leading me. It’s into a territory I’m really enjoying exploring, and the work is coming easily to me. I don’t struggle over writing any more. I used to, especially with Japan, to get enough material for an album. Eight songs a year doesn’t sound a lot but it would be a lot for me- I’d really struggle to get those eight songs ready for an album. It doesn’t happen like that any more.

‘I used to start from titles but now most pieces come from just sitting down at a piano or synthesiser. Pieces like ‘Nostalgia‘ and ‘Before the Bullfight‘ off this album came out of just messing about, waiting for something to happen. They’re the pieces I don’t think about much: they fall into place fairly naturally.

‘And very obvious piano pieces like ‘Laughter and Forgetting‘ and ‘Brilliant Trees‘ come out very easily as w”,ll- they’re very natural to me. But if they’re too obvious I don’t tend to get any enjoyment from them.

‘Arrangements tend to take up a lot of time: there are so many ways to arrange a piece of music. On occasions I’ve started a track and taken it to a certain point, then just dropped it and done a totally different version.’

And it was the exploration of different arrangements that still gives Tin Drum a place in Sylvian’s heart. More than any other Japan album, it has exerted an influence over the frontman’s career that has reached far beyond its initial impact.

‘I had the idea that every other phrase should be sound, and should alternate as much as possible. That’s all we started with.

‘So I tried out two pieces, ‘Talking Drum‘ and ‘Canton‘, with Steve just to see if it would work. It doesn’t take a great deal of songwriting to come up with pieces like those -it was only the arrangement that made both of them work. It worked so well and we enjoyed it so much that ‘Talking Drum‘ is still my favourite Japan track. The public never seemed to see it as a very live track, but it’s very important because it was how that whole concept came about.

‘After that it was very easy: I wrote the songs as usual and I had a definite idea of how they should be arranged. With ‘Ghosts‘, I knew the way that it should be arranged as I was writing it. Without Ryuichi to help out in the studio it would never have sounded like it did, but the idea of the arrangement was there from the beginning. The whole success of the Tin Drum album was purely arrangement.’

WITH SYLVIAN’S INTEREST in improvised and abstract music, not to mention the animosity that existed between he and Karn at the time of the split, it’s surprising to learn there’s recently been talk of Japan getting back together again. The rift between singer and bass player is now healed to the extent that Sylvian is to appear on Karn’s forthcoming album, but the band reformation is still only talk.

‘There was talk at one point of whether Japan should get back together or not. As a romantic idea it would be nice, but I can’t see it at the present time. The idea of working in a group is enticing after you’ve been working on your own for so long. It’s very difficult working on your own in the studio, and the idea of getting back together and being with the group again is something that appeals to everybody.

‘It almost came off, but there wasn’t enough conviction and now I’m happy that it didn’t. I’m sure that it’ll be talked about again in another five years, but I hope it’ll always be talk because I don’t think it would be a good thing. If you become more romantic about your ideals than practical, I don’t think that leaves you in the right frame of mind to say: “No”.

‘So what of the immediate future? Sylvian says he wants to travel again, but the infatuation with Japan has worn thin, and the South of France now beckons more strongly. There are formative plans for a regular band, but it’s too soon even to speculate on the line-up or the repertoire it might play.

‘It’s something I definitely want to do: I’ve just got to find the right people and I haven’t got a clue where to start looking. It’s going to take a while, of that I’m sure -it’s for the next vocal album. I might do other albums in between and work with different people, but I’d like to form a band to make at least two vocal albums and to do a tour.

‘On the other hand, I am very interested in the instrumental work which doesn’t need a band. I’d also like to play a few small dates performing the instrumental stuff, and then whichever remains the more passionate in my heart I would follow. I can’t say definitely it would be one thing; maybe I’ll do both.

‘I really enjoy writing now. I particularly enjoyed the instrumental work, though I do sometimes get tired of it. At times I feel like giving up because of the struggles of working with record companies, but I’m enjoying it too much at the moment.

‘I plan to stay in the studio as much as I can but I don’t think I’m going to start anything else of my own for a while. I might collaborate if something interesting comes up. That’ll give me something to occupy me creatively while I take time to think about what I really want to do with my own work.’

As so often in the past, Sylvian is uncertain where his artistic life will take him in the years to come. But there is a future there somewhere, and musicians who’ve been inspired by the man’s work will be glad of that.