More interesting Manafon reviews.

The Big Takeover (12 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

by Michael Toland

On Manafon, experimental singer/songwriter DAVID SYLVIAN takes the next logical step up from his previous record Blemish. That platter had Sylvian improvising alone with his guitar and keyboard, with guest guitarist DEREK BAILEY on a handful of tracks. Manafon finds Sylvian continuing down the improvisational path, but backed by a gaggle of musicians from the jazz, pop and electronic worlds, including guitarist KEITH ROWE, saxist EVAN PARKER, electronicist CHRISTIAN FENNESZ, pianist JOHN TILBURY, turntablist OTOMO YOSHIHIDE and more. The results aren’t as explosive as one might expect – Sylvian keeps the accompaniment low, even sedate, letting his accessible vocal melodies carry the songs as if he’s afraid his buddies will wake the baby. The record has such a consistent tone it’s probably better to think of it as a sustained mood piece rather than a collection of individual tracks – it certainly strengthens its appeal if you don’t look for the new “Orpheus.” Fans wishing for a return of the high craft of his early work will be disappointed by Manafon, but folks intrigued by his current direction will appreciate his continued development.

Boomkat (21 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

author unknown

When David Sylvian makes a solo album, he really throws everything into it. It’s been six years since the former Japan frontman released his masterful Blemish LP, and Manafon is its much anticipated follow-up. As with Scott Walker’s latter-day work, Sylvian’s music is far-removed from the chart-dwelling hits of his youth, instead taking on a ruthlessly cerebral and experimental agenda; alongside Walker, recent years have seen Sylvian as one of the very few artists who could be said to have challenged what it means to write and produce a song. Assisting him to this end is a roster of great improvisatory talents, supplying Manafon with a beautifully rendered, supremely detailed backdrop of timbres, textures and vibrations. Guitarists have been of particular importance to David Sylvian albums over the past ten years or so; Marc Ribot and Bill Frisell were among the key musicians contributing to 1999’s Dead Bees On A Cake, and for Blemish Sylvian struck up highly fruitful collaborations with Christian Fennesz and – perhaps most significantly – the late Derek Bailey. The latter’s striking improvisational style seems to have impacted greatly on Sylvian’s approach to songsmithery, and traces of the jazz veteran’s spidering, chitinous playing are detectable in the dissonant twangs of Tetuzi Akiyama and Otomo Yoshihide. Fennesz returns for Manafon, bringing his Polwechsel associates Burkhard Stangl and Werner Dafeldecker with him, while additionally, prepared guitar experimenter Keith Rowe appears, ranking alongside those other elder statesmen of British improvised music, John Tilbury and Evan Parker. This distinguished ensemble weave magic under Sylvian’s supervision, fabricating the finest and most ornate of sonic environments for the band leader’s rich, stately croak. Indeed, Sylvian’s vocal inevitably takes the central role, offering a melodic route through an album of ostensible disorder, reaching its finest hour during Manafon’s centrepiece: ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’. Here the singer is joined by discordant string quartet recordings – scratched and warped on Yoshihide’s turntable, while the most carefully poised of guitar and piano performances match-up against the imperious subtlety of Toshimaru Nakamura’s no-input mixing board static and Sachiko M’s intricate formation of cobweb-like sine waves. It’s amazing that all these infinitesimal articulations are heard so clearly, but this is a recording on which all the minutiae resound with great lucidity, and truly, the more listens you give Manafon, the more it reveals its complexity and brilliance. This is far from an easy or instant record, and most likely it’ll take a couple of play-throughs to get anywhere with its daringly unascertainable idiom, but once engaged, you might not hear a more enriching body of work all year.

taz.de (22 september 2009)

Der furchtlose Wanderer

By Tim Casper Boehme

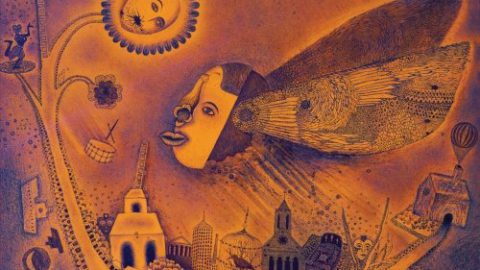

Ein Reh blickt scheu durch die Bäume. Der Wald, in dem es steht, wirkt unnatürlich grün. Auch die Pilze am Wegrand scheinen nicht dorthin zu gehören, wie bei Traumelementen schiebt sich alles ineinander. Diese Natur, suggeriert das Foto auf David Sylvians neuem Album “Manafon”, ist anders als die, die man im Freien findet. Es gibt sie nur im Kopf. Fremd und menschenleer ist es dort, zugleich sehr konstruiert.

Ein passenderes Bild für die Einsamkeit hätte sich Sylvian kaum aussuchen können. Seit einigen Jahren lebt der britische Musiker zurückgezogen in den Wäldern Neuenglands. Doch statt einer unberührten Idylle zeigt das Cover des niederländischen Künstlers Ruud van Empel einen hermetischen Fantasieraum. Auch die Stücke handeln von Introspektion und Einsamkeit. Fremd klingt die Musik dazu, scheinbar haltlos navigieren die Instrumente durch unerforschtes Klanggebiet, von Pop kaum eine Spur.

Improvisation statt Plan

Mit “Manafon” setzt Sylvian den Weg fort, den er auf seinem Vorgängeralbum “Blemish” eingeschlagen hatte. Der Meister elegant arrangierter Melancholie mit der sanft-seltsamen Stimme sang hier plötzlich über rohe Improvisationen ohne eindeutige Form. Drei Stücke von “Blemish” entstanden gemeinsam mit dem 2005 verstorbenen Freejazz-Gitarristen Derek Bailey, einem der Begründer der freien Improvisation. Für “Manafon” hat Sylvian nun die größten Namen der internationalen “Improv”-Szene versammelt. ” ,Blemish’ deutete eine Menge von Möglichkeiten an, und neben meinen eigenen Improvisationen waren besonders diejenigen mit

Derek zukunftsweisend für mich. Ich wollte herausfinden, ob es möglich ist, mit größeren Ensembles zu arbeiten.”

Am Anfang gab es wenig mehr als die vage Idee einer “modernen Kammermusik”. “Als ich die erste Aufnahmesession 2004 in Wien plante, hatte ich lediglich die Vorstellung: Wenn ich es höre, weiß ich, was es ist.” Am wichtigsten war daher für Sylvian, die richtigen Musiker zu finden. Christian Fennesz, österreichischer Gitarrenexperimentator und ebenfalls auf “Blemish” vertreten, stellte den Kontakt zum Wiener Ensemble Polwechsel her. Mit anderen Musikern wie dem britischen Gitarristen Keith Rowe, einem Gründungsmitglied der Experimentalpioniere AMM, hatte Sylvian schon vorher gesprochen. Als weitere prominente Mitstreiter kamen der Saxofonist Evan Parker, der Pianist John Tilbury und der Gitarrist und Elektroniker Otomo Yoshihide hinzu.

Seine Rolle bei den Aufnahmen beschreibt Sylvian als die eines Produzenten. Anfangs war er noch unsicher, ob es überhaupt möglich sein würde, den Musikern völlige Freiheit beim Spielen zu lassen, sie zugleich aber dazu zu bringen, sich innerhalb der von ihm gesetzten Parameter zu bewegen. Schließlich wollte er die Musiker nicht nur in eine bestimmte Richtung dirigieren, sie sollten ihm überdies die entstandenen Aufnahmen überlassen, damit er das Material nach Belieben verwenden konnte. Zu seiner großen Überraschung waren alle einverstanden, kein Musiker sagte ab. “Ich hätte alles damit tun können, ich hätte darin herumschneiden und es radikal bearbeiten können.”

Stattdessen entschied sich Sylvian dafür, die Improvisationen in ihrem Kern unberührt zu lassen und allenfalls Einleitungs- und Schlussteile zu ergänzen. Hin und wieder legte er die Instrumente der verschiedenen Sessions in Wien, London und Tokio übereinander und ließ aus dem freien Zusammenspiel eine Art minimal-invasiver Komposition entstehen. Seinen Gesang fügte er nachträglich hinzu. Die Texte entstanden beim Hören der Aufnahmen, alles, was ihm spontan einfiel, wurde notiert. Ganz zum Schluss kamen die Melodien. Was an “Manafon” sofort hervorsticht, ist die Dominanz des Sängers. Sylvian hat seine Stimme stark in den Vordergrund gemischt, durch die sparsamen, aufs Äußerste reduzierten Gesten der Musiker wirkt der Gesangspart zusätzlich isoliert und nackt. So dienen die Instrumente als akustische Lupe: “Die Bedeutung der Stimme wird vergrößert. Sie wird durch nichts verdeckt, man fühlt sich völlig bloßgestellt. Das hat eine doppelte Wirkung: Zum einen schafft sie beim Hörer ein Gefühl von Intimität, er spürt aber auch die Isolation des Erzählers.”

Viele der Texte sind in der dritten Person geschrieben, im Grunde handeln jedoch alle von Sylvian und seiner Einsamkeit. Dass er als Erzähler selten “ich” sagt, geschieht mit Rücksicht auf sich selbst – und die Hörer. Weder ihm noch seinem Publikum sollten die manchmal heiklen Themen Unbehagen bereiten. Und, so eine seiner Anfangsideen für das Projekt, jeder Satz sollte richtig klingen. Man könnte ergänzen, dass jeder Satz auf “Manafon” durchaus auch selbstbewusst klingt. Statt eines verzweifelten Eremiten meint man einen Wanderer zu vernehmen, der langsam und furchtlos in einen dunklen Wald hineinschreitet. Sylvian gefällt dieser Gedanke. “Es hat etwas Furchtloses, wenn man sich ganz offen selbst analysiert, ohne dabei die angesprochenen Dinge zu verwässern.” Gleich im ersten Stück, “Small Metal Gods”, verabschiedet er all die Götter, denen er für einige Zeit gefolgt ist. Nach Jahren bunt-esoterischer spiritueller Suche wirft er sie jetzt als “Kinderkram” auf den Müll. Die Reise ins Innere setzt sich über die gesamte Albumlänge fort.

Introspektion trifft

Introspektion allein macht aber noch kein sensationelles Album. Erst zusammen mit der freien Kammermusik, die Sylvian während der Reise begleitet, lässt “Manafon” an Luft von anderen Planeten denken. Radikaler als viele Musiker, die mit Tracks arbeiten und so die Songstruktur untergraben, verzichtet Sylvian auf jegliche Form – mit der Ausnahme, dass seine eigenen Melodien aus wiederkehrenden Figuren bestehen und meistens tonalen Charakter haben. Das Drumherum spricht eine diffusere, zerbrechliche Sprache. Sylvian ist die vorgegebenen Muster der Popmusik leid, sie haben für ihn an Reiz und Bedeutung verloren.

Der ehemalige Sänger der New Wave-Band Japan, der kurz vor dem ganz großen Durchbruch zu Beginn der Achtziger seine Kollegen verließ, hatte seither seine eigenen Experimente in Sachen Pop durchgeführt, zunächst ohne die Formsprache des Songs aufzugeben. Seine neue Freiheit eröffnete ihm eine Reihe zusätzlicher Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten. “Die Improvisationen erlaubten es mir, die Sprache in völlig anderer Weise zu benutzen. Ich konnte nüchterne Alltagssprache benutzen, die nicht klobig klang. Genauso konnte ich eine sehr poetische und suggestive Sprache verwenden, die ebenfalls ihren Ort fand. Auch bei den Melodien konnte ich auf die unterschiedlichsten Quellen zurückgreifen. ,Manafon’, das Titelstück, ist für mich wie ein Folk Song.” Benannt ist das Album nach dem ersten Sprengel des walisischen Pastors und Dichters R. S. Thomas. Der menschlich etwas schwierige Thomas war nicht sonderlich erfolgreich darin, die Gemeinde am Sonntag in die Kirche zu bewegen. Dafür schrieb er während dieser Zeit seine ersten drei Gedichtbände. “Manafon wurde für mich zu einer Metapher für dichterische Fantasie.”

Konzerte sind nicht geplant. Ob er weiter atonale Musik schreiben oder sich wieder dem Vokabular des Pop zuwenden wird, lässt er offen. Noch im Jahr 2005 hatte er mit seinem Projekt Nine Horses eine wunderbare Kombination aus Songs, Elektronik und Jazzimprovisation geschaffen. Regression jedenfalls ist kaum von ihm zu erwarten. Sein Blick ist bei aller Introspektion nach vorn gerichtet: “Man hofft immer, dass man zur Entwicklung dessen beiträgt, in das man sein Leben investiert hat.”

Gleich im ersten Stück, “Small Metal Gods”, verabschiedet er all die Götter, denen er für einige Zeit gefolgt ist

Babyblaue Seiten (13 september 2009)

CD review David Sylvian – Manafon

By Günter Schote

(11 out of 15 stars)

Um es kurz zu machen: David Sylvians neues Werk setzt die auf Blemish begonnene Reise unbeirrt fort.

Erste Reaktionen der Sylvian-Gemeinde: Gegen „Manafon“ war Blemish das reinste Bananarama-Gedudel… oder Man nehme Blemish und ersetzte den dort vorhandenen Rest Musik durch Pfeiftöne a la Darkest Birds. Sylvian selbst bezeichnet „Manafon“ als Sister piece to the Blemish-Album, trotz der thematischen und tonalen Unterschiede. So weit, so gut, aber ist das wirklich so? Und wenn ja, ist das dann gut oder schlecht?

Um es nun aber doch etwas länger zu machen…

Da steht nun ein süßes Reh im Wald und schaut liebevoll seinem Betrachter entgegen, dem vor lauter Bild gewordener Rührseligkeit die Tränen in die Augen schießen. Auf seinen klassischen Alben von Brilliant Trees bis Dead Bees on a Cake war ein solches Cover für eine Sylvian-LP/CD schlicht unmöglich, hätten Frauenmagazine dadurch doch rücksichtslos Rückschlüsse auf die Musik gezogen. Doch diese Befürchtungen muss David heute nicht mehr haben, so dass er die in seiner Musik verlorene Rührseligkeit bedenkenlos auf dem Albumcover zur Schau stellen kann.

Die Aufnahmen zu „Manafon“ begannen 2004 in Wien, wo er Sessions mit dem Österreicher Christian Fennesz, Keith Rowe und der Gruppe Polwechsel (deren Aufgabe noch immer die Erforschung des Klangs an sich zu sein scheint) aufnahm. „Reduktion“ lautete das Motto, ebenso wie „Spontanität“. 2006, parallel zu „When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima“, nahm er dann Sessions mit Otomo Yoshihide, Sachiko M., Tetuzi Akiyama und Toshimaru Nakamura auf. Dies sind japanische Musiker, die sich als „Nicht-Musiker“ bezeichnen und vor allem der Improvisation im Minimalistischen frönen. Endlich im 2007 fand die letzte Session mit Evan Parker, John Tilbury, Marcio Mattos und erneut Christian Fennesz in London statt. Im November 2008 konnte David Sylvian „Manafon“ kurz und bündig (so wie es ja auch die Aufnahmesessions waren) in seinem Studio mischen und die Tonwerdung war abgeschlossen. Als Komponisten werden daher auch folgerichtig neben Sylvian die beteiligten Musiker aufgeführt.

Dies als „kurze Geschichte“ zur Entstehung des Albums. Zurück nun zum süßen Reh des Covers und weil dies allein nicht abendfüllend ist gleich weiter zur…“Musik“…

Muss ich auf jeden „Song“ einzeln eingehen? Nein. Aber wer weiß, wozu mich diese Rezession führt. „Small Metal Gods“ eröffnet das Werk. Minimalistisch und selbstverständlich Lichtjahre entfernt von Stücken wie „Nostalgia“ oder „I Surrender“, aber noch immer in den Grenzen, die er mit Blemish gesteckt hat, vielleicht sogar nicht ganz so extrem. Seine wunderbare Stimme legt sich über Töne, erst gegen Ende begleitet die Akustikgitarre seinen kurzen „Chor“-Gesang, der das Stück beendet. Applaus für die „Single“ des Albums.

Wer mit Blemish oder gar mit Sylvian generell nichts anfangen konnte, für den wird auch „Random Acts of Senseless Violence“ eine Zumutung sein. Doch den Sylvianisten, den Blemish beim ersten Hören noch ratlos zurück ließ (jaja, ich rede u.a. von mir!) kann das Stück nach mehrmaligem Hören fangen. Gleiches gilt für das zentrale Stück „The Greatest Living Englishman“.

Blemish minus Restmusik plus Pfeiftöne: Nein, so einfach kann man die Rechnung dann doch nicht machen. „The Greatest Living Englishmen“ verleitet jedoch dazu. Aber für meine Ohren ist hier deutlich ein Konzept, ein roter Pfaden gar, zu erkennen. Oder liegt das doch am vorbehaltlosen Sylvianlieben, das mir eigen ist? Vielleicht erstmal den Rotwein zur Seite stellen und „Garden Party“ auflegen um wieder in diese, meine Welt, zurückzukehren? Nein, das wäre doch feige. Und da David nicht feige ist, gehe auch ich den Weg mit ihm weiter: Er kehrt nicht zurück zum Harmonischen. In „The Greatest Living Englishmen“ nutzt er das musikalische Konzept von Blemish, jedoch ohne dessen graue Monotonie. Töne, Akustikgitarre, das Knistern des Vinyls, Sylvians Stimme, dies sind die Mittel, die „Manafon“ bestimmen. Rhythmen findet man wie schon auf Blemish keine.

„Manafon“ – was ist das eigentlich? Eine walisische Stadt. Wer hätte es gedacht? In dieser wirkte lange Jahre seines Lebens der im Jahre 2000 verstorbene walisische Poet R.S. Thomas, mit dem sich Sylvian auf diesem Tonträger auseinandersetzt. Der Anglizisierung der walisische Sprache entgegenzuwirken, dies war seine Berufung – nein, der größte lebende Engländer wird man so nicht. Sylvian nennt, dies am Rande, sein neues Werk „sehr englisch“, nicht britisch.

Auf Rain Tree Crow befand sich mit „Boat’s for Burning“ ein wunderschönes Stück von 35 Sekunden Länge. Auch „Manafon“ bietet mit „125 Spheres“ einen gelungenen 28-Sekunden-Shortie. Doch Länge und Kürze sind in dieser offensichtlichen Abwesenheit von Struktur ohnehin unerheblich, unwichtig. Und Schönheit schwingt allein im Ohr des Hörers.

Atmosphäre, Töne, Sylvians Stimme. Das Titelstück würdigt abschließend den „Sprachkämpfer“ R.S. Thomas und wenn man sich an die Abwesenheit gewohnter Musik gewöhnt hat, so wähnt man sich fast in einem ganz normalen Stück Musik des David Sylvian.

Beim ersten Hördurchgang fragte ich mich noch, wie ich dies „bewerten“ soll. Diese Frage ist einer Antwort gewichen: Sylvian, der sein irdisches Gastspiel derzeit als Eremit in einem Blockhaus fristet, schlug mit Blemish einen Weg ein, der ihn fortführte von Struktur und Althergebrachtem. Mit seiner Musik kann man sich mittlerweile nicht nur als intellektueller Wichtigtuer bzw. Schöngeist präsentieren, nein, man kann sich mit ihr auch nicht „bloß“ auseinandersetzen, man muss mit ihr ringen. Ob man dieses Kämpfchen am Ende gewinnt oder verliert ist nicht entscheidend: Hearing is the road…

„Manafon“ gibt es übrigens auch als Limited Edition. Diese Ausgabe enthält neben dem Album im 5.1-Mix auch einen 55 minütigen Film namens „Amplified Gesture“, der die Beteiligten zu Wort kommen lässt und das Album zu erklären versucht. Die japanische Version enthält zusätzlich einen Remix von „Random Acts of Senseless Violence“.

PS: Im Anschluss an wiederholtes „Manafon“-hören legte ich wieder „Blemish“ ein. Wohl dem, der dies als gelungenes Wochenende empfindet!

igloo

CD review David Sylvian – Manafon

By Jus Forrest

(August 2009) David Sylvian’s career has spanned a thirty-year period, initially finding its way through the popular New Romantic movement with the band Japan. Sylvian subsequently went on to produce a quality body of mature solo work, his debut emerging in 1984 with Brilliant Trees. Going from strength to strength ever since, he’s reinvented himself musically at various stages along the way.

His latest release, Manafon, is an unconventional work and perhaps one of the most diverse to date, and testament to his development. It sees Sylvian stripped bare of any lavish trimmings. The compositions reach out with naked hands, clinging to intelligent and sometimes complex observations and rigorous study of character.

Sylvian scratches the edges of some dark surfaces; however the centrefold is even more expressive with its hues of jaded normality – a conceptual status throughout.

Sylvian portrays deep insights with his lonely textured vocals, grasping the heart of the subject and shaping it in a way that only his own strength of voice could direct. Instrumentation is sparse yet effective and orchestrated in a unique way – the diverse sounds intervene at all the right moments integrating well with the mood. His haunting lullaby has a strong sense of purpose – pivoted centrally throughout the album against its dark fabric – the colours of which are all exceptionally responsive. With production that’s crystal clear – every creek or stirring within the atmosphere can be heard – all reacting and responding with an immense sharpness.

“Maybe I’m attracted to the stories of individuals who search for meaning on their own terms,” says Sylvian. “But what I’m fascinated by is the devotion to a creative discipline. The meaning with which the work imbues the life regardless of its reception and, to

a certain extent, its importance.”

Manafon isn’t just a listening experience – it’s a work that encompasses every nuance of explicit chamber instrumentation, melody and structure – the qualities of which become more engrained with every listen.

Tiny Mix Tapes online (21 september 2009)

CD review David Sylvian – Manafon

By Joe Hemmerling

(2 out of 5 stars)

The ability for the members of a band to parlay its success into artistically relevant solo careers is not a foregone conclusion. Often, artists will either hew too closely to the sound that made them popular, or they’ll indulgently play the dilettante in whatever genre happens to grab their fancy at the moment. Credit is due, then, to David Sylvian for refusing to spend the past three decades resting on Tin Drum’s laurels. Like 2003’s Blemish, Manafon eschews traditional pop conventions and prominently features Sylvian crooning over a minimalist instrumental accompaniment. This time around, however, Sylvian is accompanied by 60s free jazz pioneers and members of AMM. They’ve replaced the heavy synth wash of Blemish with some sporadic acoustic guitar pickings, wailing brass, and random bursts of twittering feedback or static. The chief element of nearly every song is a stillness approaching silence, with only Sylvian’s voice hinting at anything resembling a melody.

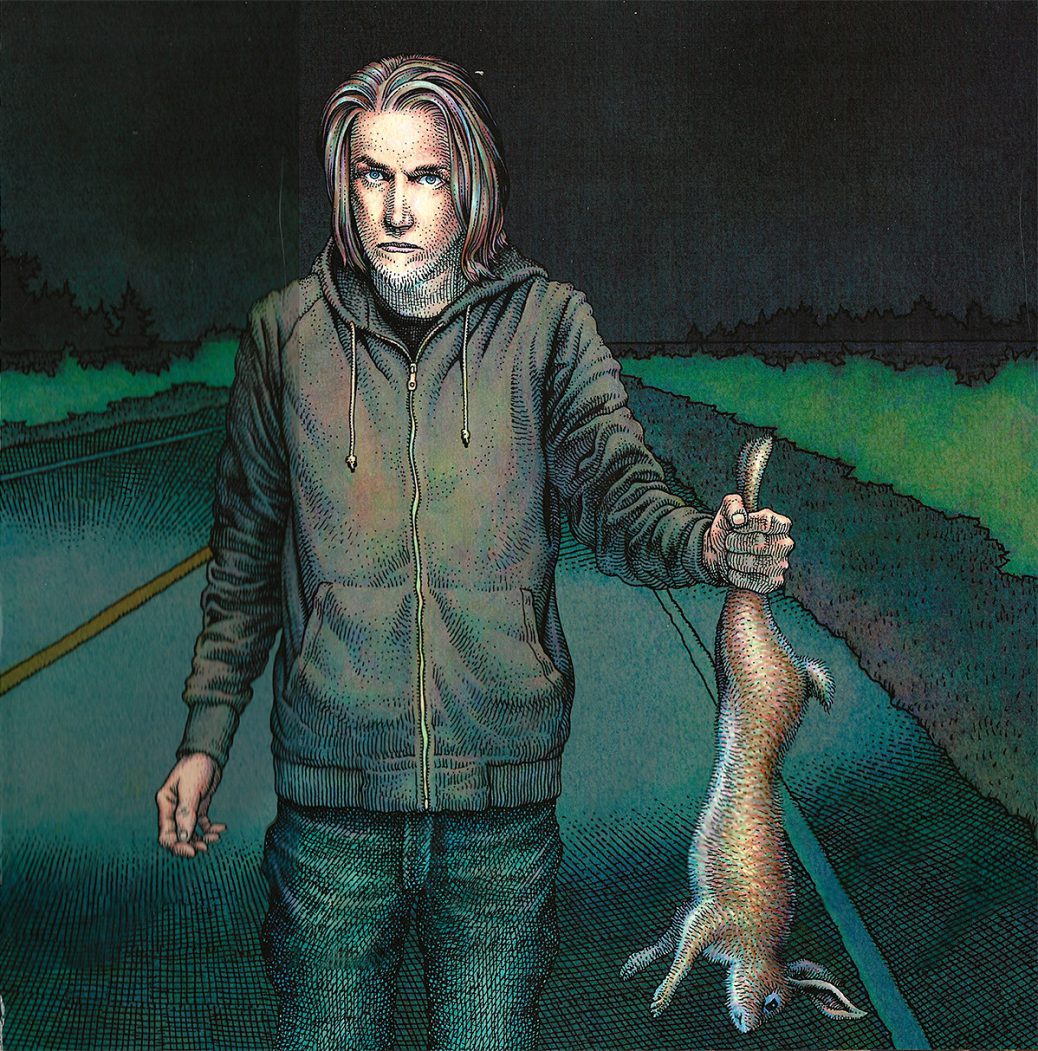

It’s a sonically ambitious undertaking — and miles beyond what many of his peers in the late-70s post-punk scene are currently doing — but ultimately, the album gets lost in its own conceit. Manafon starts out promisingly; “Small Metal Gods,” easily the most musical entry on this disc, is the only song in which the backing musicians sync up with Sylvian’s smooth, detached tenor. But the relative warmth of this track soon gives way to the quietly ominous “The Rabbit Skinner,” where Sylvian’s vocals are at their most naked and vulnerable, haunted by Marcio Mattos’s warbling cello and Evan Parker’s moaning saxophone. Still, nothing really feels like it’s happened yet. These sparse, atmospheric pieces come across like lengthy prologues setting the stage for a great release or catharsis. It’s track three where my appreciation for Manafon dropped off precipitously because it was at precisely this point where I realized that the first two tracks were not merely “creating an atmosphere” — that this was, in fact, what the entire album was going to sound like. It was with mounting horror and despair that I realized I had to slog through seven more tracks (many of which run from five to 10 minutes in length) of the same dry crooning and the same sporadic, arrhythmic accompaniment.

While I appreciate the degree to which Sylvian and the AMM Musicians are unraveling the popular song and pushing at the boundaries of music, this appreciation does nothing to enhance my enjoyment of this record. Perhaps the biggest problem is that, for as opaque as these compositions are, I’m not really sure that Sylvian and co. are actually doing anything that ground-breaking. Nick Cave’s “A Box for Black Paul” and Lift to Experience’s “Down Came the Angels” both accomplish similar effects, but both Nick Cave and Josh Pearson are content to do in one song what Sylvian apparently needs to drag out for an entire album. The result is a record that blows right past ’challenging’ and into ’trying’ territory. Even Sylvian’s painstakingly crafted surrealist narratives wind up getting lost simply because I could not muster the mental energy to focus on any song for its entirety. If the purpose of avant-garde music is to challenge my mental framework for what qualifies as a song, and to push me to the limits of my enjoyment, then Manafon has succeeded in a way that bands like Ruins, Yellow Swans, and MoHa! could not. Yet I don’t feel that I’ve gained anything from having my limits so violently transgressed. While no one could accuse Sylvian of playing it safe, the exercises that make up Manafon are neither experimental nor aesthetically pleasing enough for me to recommend this album.

OOR magazine online, Netherlands (21 september 2009)

CD review David Sylvian – Manafon

By Jacob Haagsma

Evan Parker, Keith Rowe, Polwechsel, Otomo Yoshihide, John Tilbury, Sachiko M: geen namen die je snel in dit blad aantreft. Maar als deze mensen, toppers uit de improvisatie-avant-garde, hun talenten in dienst stellen van David Sylvian, wordt het een ander verhaal. Op zijn vorige soloalbum Blemish ruimde Sylvian al een belangrijke plek in voor de improvisaties en abstracties van Christian Fennesz en wijlen Derek Bailey. Deze plaat, waarop Fennesz een belangrijke coördinerende en aansturende rol had, is daar een logisch vervolg op.

Het is een uiterst avontuurlijk soort kamerpop, gegroeid uit vrije, meest introverte improvisaties en later gekneed om Sylvians songvormen te kunnen dienen. Onverwachte ritsels, notenslierten of subtiele elektronische verstoringen slingeren zich in het geluidsbeeld om Sylvians omfloerste zang. Reken dus niet op meefluitbare wijsjes, maar dat hadden we – gezien de richting waarin Sylvians carrière zich bewoog vanaf zijn dagen in late glamrockband Japan – ook niet hoeven verwachten. Bij oppervlakkige beluistering zijn de nummers, die rustig zes of elf minuten in beslag kunnen nemen, wel wat eenvormig in hun trage, intieme temperament. Maar stug doorluisteren haalt een wereld aan sferen en avontuur boven, een plaat vol avontuur waarop je niet snel uitgeluisterd raakt.

The Line Of Best Fit (21 september 2009)

CD review David Sylvian – Manafon

By Jude Clarke

David Sylvian has been on one heck of an artistic journey since his first musical appearance as front man in the early, New York Dolls-apeing incarnation of 1980s favourites (and thinking-person’s New Romantics) Japan. That gradual, but ultimately dramatic evolution, from swoon-inducing lead singer to fiercely intelligent and challen

ging avant-garde writer and performer has continued, and quite possibly attained its highest peak yet on this, his twenty first post-Japan release.

The first thing to say about this astonishing work is that it’s less an album of “songs”, more almost an audio poetry book. Before I could even begin to start marshalling my thoughts sufficiently to write about it, I felt compelled to sit and transcribe the lyrics to each track (bar the instrumental ‘The Department Of Dead Letters’), the better to mull over and savour the striking images, ideas and above all emotions that they articulate.

To the sparsest, sparest musical accompaniment, Sylvian seemingly lays bare a troubled soul. It is hard not to interpret the words as disturbing and personal, particularly in the repeated references to suicide: “My suicide, my better days, there’s nothing I regret” from ‘Small Metal Gods’, for example, or pretty much all of ‘The Greatest Living Englishman’, which taken as a whole reads like an extended suicide note, or at best the story of a failed attempt. It tells (autobiographically?) of a man who felt that “the love he engendered would never be enough”, who encountered “plastic-coated surfaces” and “shut himself outside” and appears to be singing from a hospital bed where “the curtains round the bed are drawn / Broadcast voices from the ward / The humming of machines are heard”. The reference to “a man with so much self in his writing” would only appear to confirm that this is Sylvian telling his own story. The description of a “child of the 50s / with no common sense / no easy resting place” in ‘The Rabbit Skinner’ also sounds autobiographical.

In ‘Random Acts of Senseless Violence’ Sylvian moves one step away from the purely personal, and manages to evoke, probably better than any writer that I’ve read thus far on the subject, the feeling of non-specific, generalised dread and fear that have seeped into the general psyche since 9/11 and the London bombings. Bald couplets like “The targeted will be non-specific / We’ll roll the numbers, play with chance” and, especially, “Someone’s back kitchen stacked like a factory / With improvised devices, there’s bound to be injuries” and “No phone-ins, no courtesy, no kindness / And the future will contain random acts of senseless violence” produce a genuine chill, and a shock of recognition that is the mark of genuinely affecting poetry.

A female protagonist also appears, elusive, withdrawn, and mysterious on ‘Snow White in Appalachia’ (“Sometimes you’re only a passenger in the time of your life”) and ‘Emily Dickinson’ (“Without so much as a kiss, or the comfort of strangers / Withdrawing into herself”). The album’s pervasive sense of hopelessness and nihilism is best illustrated on the former, with the line “And there is no maker, just an exhaustible indifference”.

One of the many impressive things about the lyricism Sylvian displays is that you notice, almost as an afterthought, how he manages to produce perfect rhymes, time after time, without sacrificing the sense of the words, or ever making it sound contrived. Just look at these lines, from ‘Small Metal Gods’:

I’ve placed the gods in a ziplock bag, I’ve put them in a drawer

They’ve refused my prayers for the umpteenth time, so I’m evening up the score

Small metal gods from a casting line, from a factory in Mumbai

Some manual labourers’ bread and butter, and a single-minded lie

Beautiful, meaningful and they sound as good as the meaning that they convey.

What of the music, then? Sylvian assembled a collection of expert musicians in the series of sessions that created this album (the first in 2004, the last in 2008), whom he describes as a “remarkable group of individuals who’ve pursued the less trodden path where music and free improvisation are concerned”. The resulting accompaniment is sparse, spare, sometimes interjecting fiercely to punctuate the lyrics and Sylvian’s beautiful, tremulous yet underplayed vocal, at other times stepping back and letting the words and voice do most of the work. It also succeeds in genuinely mirroring or conjuring up distinct and specific moods and feelings to complement those conveyed in the words.

In summary, then this album is one to immerse oneself in. Accepting and embracing the slow, painstaking pace, and allowing the words, sounds, ideas and that voice seep in (possibly whilst reclining in a darkened room) will truly reveal its manifold, dark, truthful and brave appeal. One of the most striking and impressive releases of the year.

Spiegel online (8 september 2009)

Die wichtigsten CDs der Woche: Manafon

By Jan Wigger

Wohl niemand möchte Freunde haben, die das wundervolle Cover der neuen David-Sylvian-LP “Manafon” (oder Americas Soundtrack zu “The Last Unicorn”) kitschig finden. Doch auch die völlig vereinsamt klingende Kunstmusik, die Sylvian 1987 auf dem gigantischen “Secrets Of The Beehive” perfektionierte, löst bei manch strammen Optimisten Panikattacken aus. David Sylvians improvisierte Spärlichkeiten haben keinen Raum und keine Zeit. Einzig Scott Walkers “The Drift” (2006) und das Jahrzehntwerk “Mark Hollis” (1998) dienen als Vergleich, wenn Sylvian in “Snow White In Appalachia” und “Random Acts Of Senseless Violence” die Natur der Stille erforscht. Dennoch nehmen unter anderem der begnadete Wiener Christian Fennesz sowie John Tilbury, Keith Rowe und Otomi Yoshihide (der in “The Greatest Living Englishman” altes Vinyl knistern lässt) teil, was fraglos auch nichts an der magischen Undurchdringlichkeit des Sylvianschen Dickichts ändert. Das in Geschmacksfragen unbestechliche Magazin “Wire” tat das einzig Richtige und ehrt den Mann, der als Sänger von Japan fast einmal ein Popstar war, in diesem Monat mit einer Titelgeschichte. Holzfällerhemd, Bart und verlassene Blockhütte sind für Sylvians Einsamkeitsbegriff übrigens nicht von Belang. (8)

Orange County Weekly (16 september 2009)

CD Review David Sylvian, Manafon

By Ned Raggett

In some ways, David Sylvian is trapped in elegant amber, thanks to his stellar work fronting Japan, the U.K. act that evolved into a perfect art-dance bridge from mid-’70s David Bowie to Duran Duran. But the numerous impulses that have driven his muse for years, including his near-countless partnerships with performers ranging from Robert Fripp and Ryuichi Sakamoto to younger gun

s such as neo-electrogaze icon Fennesz—not to mention an often-intense private life Sylvian has guarded as carefully as his public image—has meant music that long resisted easy categorization. For any short, pop-oriented ballad of his, one could name a cryptic, lengthy composition in turn.

Manafon, his first full solo release since 2003’s Blemish, continues and almost summarizes this mix of styles, and arguably only one thing—his still-amazing voice, the cracks and strains of age adding a rough resonance without ruining it—connects him with even his recent past work. Spare, distressed arrangements, created from fragments of performances with a dizzying array of avant-garde collaborators (including Fennesz; Japanese multi-instrumentalist Otomo Yoshihide; and former and present affiliates of AMM such as saxophonist Evan Parker, guitarist Keith Rowe and pianist John Tilbury) emphasize space and silence rather than full-ensemble swing, his voice sitting forward in the mix with a sudden, naked intensity. When he first appears on the compelling opener “Small Metal Gods,” the effect is startling, even as he softly croons about intense emotional distress—perhaps even more of a hallmark of this album as it was of Blemish.

Song for song, Manafon’s flowing, crumbling beauty suggests striking points of comparison: Frank Sinatra’s most blasted, bleak songs; the flowing, uneasy depths of mid-’70s Miles Davis; the abstract serenity of Talk Talk’s Laughing Stock. But in the end, it is exactly what it always was—“just” another David Sylvian album, apart from anything but itself.

The Wall Street Journal (11 september 2009)

In a Sylvian Groove: A new album inspired by a dead poet

By Jim Fusilli

Few musicians have traveled as far from their original style as has David Sylvian. He met the public in 1974 as the vocalist for Japan, a British commercial pop group in the vein of Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet. His new album, “Manafon” (Samadhisound), is a fragile, challenging, experimental work that uses its underpinning whispered, disquieting sounds and music; at times, his voice, as rich and evocative as ever, seems to perch on what’s absent in the haunting background, its timbre and resolve keeping things from falling apart. The life and poems of R.S. Thomas (1913-2000) provided inspiration: The album takes its title from the Welsh village in which Thomas, an ordained priest in the Church of Wales, lived and served as a rector.

“It’s such a set of intersecting characteristics within him, profound faith in God and then the questioning of that faith,” Mr. Sylvian said of Thomas when we spoke by phone. “I love the dichotomy. His mission was the betterment of his life and the lives of others, but his austerity was detrimental to it. Everything in him is pared down to the essential. The man himself takes on a sort of a tragic-comedy element. He wanted to uplift humanity, yet when he saw his parishioners coming down the lane he’d hide behind bushes to avoid them.

At once, “Manafon” is completely unexpected and yet a logical progression of Mr. Sylvian’s development as a writer and musician. Since he began his solo career in the mid-1980s, he’s worked with jazz musicians Jon Hassell, Mark Isham, John Taylor and Kenny Wheeler; experimental guitarists Robert Fripp and David Torn; and pianist Ryuichi Sakamoto, with whom he’s collaborated on several projects.

Mr. Sylvian considers “Manafon” a sequel of sorts to his “Blemish,” released in 2003. But that experimental album, in which the delicate melodies hover above electronic waves and ringing guitars, was recorded in six weeks. Work on “Manafon” began in 2004, over a seven-day period in Vienna, where he convened musicians who included members of the free-improvisation group Polwechsel.

“Everything was pretty much open,” he said. “But there was the question of how do I steer incredibly talented musicians in the direction I want to go. I was mining for a particular kind of gold only I knew I was looking for.”

Mr. Sylvian took the recordings home, but he didn’t work on them for a year until “I went into my studio, played them on my computer, and started drawing out the lyrics and melody. It was a form of improvisation for me.” Later, he recorded a session in Tokyo with a different set of musicians. Finally, saxophonist Evan Parker, pianist John Tilbury, double-bassist Marcio Mattos and guitarist Christian Fennesz, who played on the Vienna sessions and “Blemish,” gathered with Mr. Sylvian in London. He finished the album in his studio late last year. Mr. Sylvian pays tribute to the musicians in the film “Amplified Gesture,” which is included in a limited edition of “Manafon”; excerpts from the film are available at www.manafon.com.

“Manafon” has more in common with the music of Edgar Varèse, John Cage and Morton Feldman than the so-called New Romantic pop with which Mr. Sylvian was associated some 35 years ago. The song “Emily Dickinson” rests uncomfortably on a bed of low growls, static, distant sparks and what sounds like a wolf’s call but actually is Mr. Parker on sax. In “The Rabbit Skinner,” Mr. Mattos’s cello and Mr. Parker’s sax make seemingly random sounds that Mr. Sylvian connects with a melody. “Small Metal Gods” is a folk song in slow motion, while the haunting piano by Mr. Tilbury adds a chill to “Random Acts of Senseless Violence.”

“It’s a matter of paring down,” Mr. Sylvian said. “You just try to keep the arrangement of the piece sparse and not decorous. There’s a freedom or liberation in the eradication of any recognizable form.” Of the musicians, he said, “They are pulling back, holding back, not developing melodic lines, ignoring tonality, sonority, and I’m fleshing it out to add a melodic vocal line.”

With its vague traces of David Bowie and Bryan Ferry, Mr. Sylvian’s voice is resonant, intensely emotional yet almost conversational. And then there are his lyrics inspired by Thomas, who was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1996 and whose work is largely centered on Wales, its people and the poet’s spirituality. Even admirers concede that Thomas was a bitter man who led a severe existence.

The title track, which closes the album, alludes directly to Thomas—”There’s a man down in the valley who is moving back in time”—as does “The Greatest Living Englishman” and, perhaps, “The Rabbit Skinner,” with these opening lines: “As a God, everything was felt to exist/As a man, he settled for less.”

“The album has twin themes of disillusionment and creativity,” Mr. Sylvian said. “It’s an album that poses a lot of questions rather than providing answers. My experience as a writer was to live through an experience then comment upon it. Here, I’m trying to live through the work itself.”

The lyrics to “Small Metal Gods,” the first song he worked on, indicate he was aware how different “Manafon” would be from his previous works: “It’s the farthest place I’ve ever been,” Mr. Sylvian writes. “It’s a new frontier for me.”

—Mr. Fusilli is the Journal’s rock and

pop music critic.

The Guardian (11 september 2009)

David Sylvian: Manafon

By Maddy Costa

(4 out of 5 stars)

Like much of David Sylvian’s 21st-century work, Manafon is a forbidding proposition. Entrenched in the improvisational avant garde, it offers nothing in the way of conventional rhythm and few demonstrable melodies. Adopt a suitably furrowed brow, however, and the album becomes mesmerising. Sylvian’s subjects are life’s loners and losers, and he regards them with a wry detachment and acute sympathy that is echoed by his collaborators. The effect in the album’s 11-minute centrepiece, The Greatest Living Englishman, is devastating: every musical phrase feels strangled and thwarted, while Sylvian delivers the suicide note of a man whose life is “such a melancholy blue, or a grey of no significance”.

The Wall Street Journal (11 september 2009)

David Sylvian and the Mysterious Sound of Inspiration

By Paul Sharma

Stretching pop music to the point where it reaches the avant-garde is no easy feat. But over the course of 30 years, starting as a teenager with the New Romantic band Japan and through a series of acclaimed solo albums, David Sylvian has successfully navigated the musical opposites of improvisation and composition, tonality and atonality. Along the way he’s worked with a changing ensemble of top-flight musicians from the jazz and electronic worlds.

Mr. Sylvian’s new release, “Manafon,” which comes out next week, brings together leading figures from jazz improvisation scene, including Evan Parker, John Tilbury and Keith Rowe, as well as the electronic musicians Christian Fennesz and Otomo Yoshihide. Each piece of music on the new album was improvised and recorded in one take. Mr. Sylvian added his vocals at a later stage, basing the melody on the improvised themes and writing the lyrics on the spot. “Manafon” is a sparse work from start to finish, with Mr. Sylvian’s minimalist melodic lines upfront in the mix, working against an abstract musical background. But it is lyrically dense and explores themes such as faith and solitude — in spirit close to the films of Ingmar Bergman. The result makes for intense listening; “Manafon” is unlikely to be played as background music.

We talked with Mr. Sylvian about his new release at his management’s office in West London.

Q: How would you describe the working process behind “Manafon”?

I’ve tried to create a modern chamber piece, in the sense of chamber music as well as theater, where there is a central narrator, but every slight nuance around them adds or changes the meaning of the work. So, I wanted a dramatic intimacy, but sense of a profound isolation of the main character. There is an economy of means and I tried to strip the work back to the bare essentials — this has been an ongoing process for me. I think I have found the right context with this group of improvisers, with enough silence in the music, so that the voice could make its presence felt.

Q: And that voice added after the improvisation?

There was nothing written when we went into the studio — this was very much free improvisation. So, the selection of the group of musicians for each improvisation was paramount. I recognized on the day which pieces could work for me. The process was that I took the material away and then wrote and recorded the vocal line over in a couple of hours. So I couldn’t analyze my contribution and that in a way was my form of improvisation — and I enjoyed the rapidity of response.

Q: The resulting vocal lines seem stripped back.

The improvisations have minimal melodic lines, but I think that the vocal melodies are richer and quite folk-like. They are drawn out and they don’t repeat very often, so in that sense they are complex. So I didn’t shy away from melody — I enjoy melody — they are all suggested by the improvisation and there is nothing in the vocal that isn’t at least hinted at by the improvisation. It was important the vocal felt integrated and not layered on, even though it was recorded at a later date.

Q: It seems that the lyrics are much less personal than on previous work.

That’s right. The opening track is in the first person, the rest are not. Recently, I wrote a piece for another project and I had to recast it in the third person as it became too much.

For me now, the idea of stories has become more attractive, and I found could speak more home truths that way, without it becoming overwhelming. So, it is a cloaking mechanism for an intensely personal record. It was definitely an unburdening.

Concertzender.nl (7 september 2009)

Listen to 5 complete Manafon tracks

Trackset

1. The Department of Dead Letters.

2. Manafon.

3. The Only Daughter (Blemish).

4. The Greatest Living Englishman.

5. Blemish (Blemish).

6. Small Metal Gods.

7. Randon Acts of Senseless Violence.

8. She Is Not (Blemish).

9. Snow White in Appalachia.

The Wire (october 2009 issue)

David Sylvian: Manafon

By Ian Penman

The pick-up group of elite improvisors might be new, but David Sylvian’s song remains the same, says Ian Penman

Manafon is the first time David Sylvian has seriously disappointed me in (gosh) 30 years – although, if it’s any consolation, it’s hardly due to any lack of ambition on his part. The portents feel great: if you thought 2003’s Blemish went out on a limb you ain’t heard nothing yet! Where the gorgeous, thorny, nonpareil Blemish had intermittent spiky/gooey interjections from Derek Bailey and Christian Fennesz, here Sylvian’s cherry-pick pick-up group includes players from AMM (Rowe, Tilbury) and Polwechsel (Dafeldecker, Moser, Stangl), and Evan Parker and Otomo Yoshihide and Sachiko M and more.

Sylvian’s such a convert to Improv there’s even a film for Manafon entitled Amplified Gesture, included on a special box set edition of the album, in which everyone but David talks about how they came to it and what it means and why they love it and what its challenges are. The bad news is: the back-seat absence of David from the film is unfortunately balanced out by his looming centre-stage presence on the CD. This is music that sounds as if it was made in two very discrete spaces: one for David, and one for everyone else. Which kinda begs the question: why bother with group improvisation as a new way to go for your Song, if you’re going to end up saying ‘Include me out!’, record your songs separately, and then just slap them over everyone else’s subtle breath-trace work?

The idea sounds great – a meeting of song and free texture – until you start to look deeper. If you’ve been singing a certain way for 35 years, how easy is it going to be to just jettison that and work in a different way?

(Answer: he doesn’t even try.) And is David Sylvian really the man for this particular go-with-your-messy-instincts job? (Answer: not on this evidence.) Like any kind of art practice you have to learn patience, sensitivity to temperature, moment, momentum and (here) the psychology of the people you play with. Sylvian appears to have plumped for Option B – taking the work of these elite players and recording his usual vocals over the top. Which could make you feel very cynical about the whole enterprise, and reignite accusations Sylvian’s faced in the past (unfairly, I’d say) about a certain boutiquey pick ’n’ mix attitude on his part towards sidemen. (And these are sidemen: it’s not like David Tibet, say, where it says: “On this album Current 93 are:…” and then a democratic list. This is A Work By David Sylvian.)

After listening the heck out of Manafon for three weeks, all I retain of its nine tracks, its dream list of free music luminaries, is exactly this: one dark arc moment of Evan Parker’s sax for ten to 15 seconds, and… and a lot of David Sylvian. His voice is mixed way up, but never for a second sounds – well, mixed up. It’s never for a moment part of the texture of the other players’ improvisations. So, having gone to the trouble of assembling all this free talent – to help evade old forms and investigate new vocabularies for your Song – why then alter your voice not a jot? The songs index various extreme moods (terror on the rather clunky “Random Acts Of Senseless Violence”; exile and exiled belief on “Small Metal Gods”, “The Greatest Living Englishman” and the title track; elsewhere, death and drugs and isolation), but the timbre and intonation of his voice just don’t change one whit from song to song.

Blemish, too, was experimental – but it was also human, warm. Manafon by comparison feels inert, half-realised; his vocals feel oddly clinical, detached, set in (s)tone. Singing, he never sounds like he was in the same timezone or mindset as anyone/everyone else; consequently no Group Mind ever catches fire here. Why get the best Improv players in the world – people who on average need a good 15 minutes to get going, as it were – and then but snip them off at two or five or ten minutes? There is one instrumental track here (“Department Of Dead Letters”), but given that it is only 2’26” – well, you see the problem. Things are barely allowed to get going before it snips shut.

All told, it has the opposite effect to what I assume Sylvian foresaw. Which is to say on most of the tracks here, you find yourself just longing for his voice not to come in again – you just want to hear how the hired help were that day, what the temperature was in the room, what jokes were cracked, whose head wasn’t on straight, who could hear the emerging light. (Or: why not just buy the new Polwechsel/Tilbury CD?) It just feels like Sylvian was the wrong man for this particular job: he can’t let go, fall into the flux, the mess, the particulate spill, the unfocused group sunrise and exploration, the same dirty water as everyone else, sweats mingling, unfamiliar salts on the tongue…

And maybe he knows it – as there’s a line here that could serve as canny autocritique: “And you balance things/Like you wouldn’t believe/When you should just/Let things be.” Or, to quote a favourite line from Welsh poet RS Thomas (subject of the title track): “The embryo music died in his throat.” Replace that ‘in’ with ‘by’ and you’ve got the whole story right there.