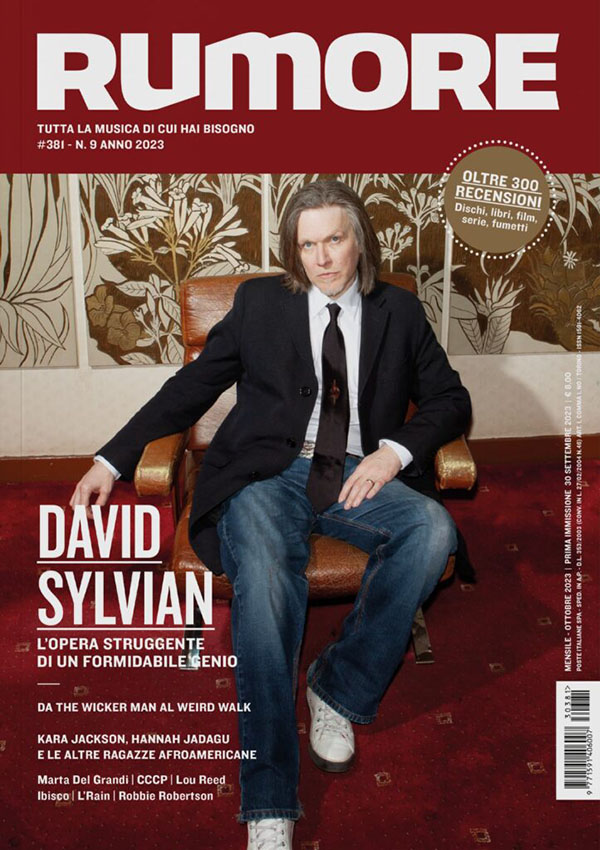

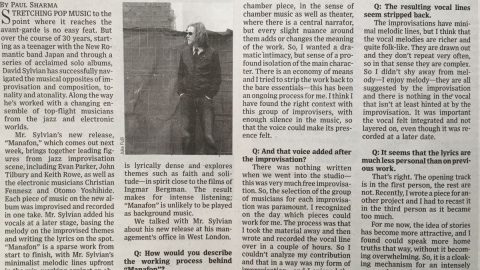

DAVID SYLVIAN – THE TOUCHING WORK OF AN IMPRESSIVE GENIUS

The magazine includes an interview with Chris Bigg about working with David Sylvian and the making of the artwork for Sylvian’s releases.

Translations kindly provided by Marta Roia

RUMORE N. 381 – page 28

DAVID SYLVIAN – The Gentleman Alchemist

by Letizia Bognanni and Daniela Liucci

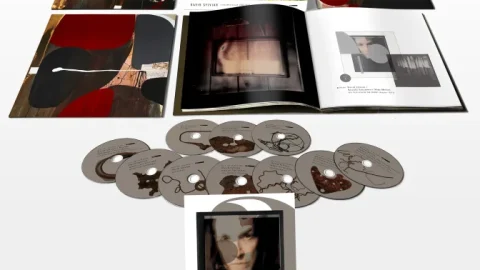

Do You Know Me Now?, reads out the title of the new David Sylvian’s box set, question that sounds ironic considering that we are speaking about an enigmatic and elusive musician, so reluctant to be in the spotlight and under the show business rules that he firstly abandoned his Japan, for too much success, and then a major to establish his own label. It is precisely the solo works published by the latter, Samadhi Sound, that are collected in the slipcase, whose release gives us the opportunity to retrace the story and the philosophy of one the most fascinating artists in music history.

RUMORE N. 381 – page 30

Chris Bigg – The art to visualize sound

by Daniela Liucci – artwork by Chris Bigg

The devil is in the details, says an adage. And it’s especially there when it has to inspire, provoke and cause you to think. Which in the end has been the philosophy of an artist like David Sylvian for more than 20 years: music is a crossroads of ideas, influences, feelings, juxtapositions, intuitions, experimentions. And it is visions, images. Which must always be able to describe sound. At the point of not being able to distinguish anymore where the former start and where the latter ends, and vice versa. It is an extreme form of freedom, which demands a detail-oriented job, neverending, an almost obsessive care, always new elements. Something very different from covering back and forth the corridors of a record company everyday, asking permission to express yourself, and most of the times without receiving an answer. Music, for Sylvian, isn’t – and it has never been – business, Chris Bigg tells us. Graphic designer, art director, former senior designer at A4D, partner in V23 studio (as well as the maker of covers for Cocteau Twins, Dead Can Dance, This Mortal Coil, Pixies, Breeders, etc…) and Sylvian’s collaborator for more than three decades. With him he worked on infinite projects: covers, posters, tour books, and books, translating in graphic design his soundscapes, sharing the concept of symbiosis between music and image. And he didn’t draw back to the call of Universal, to gather up all the Sylvian works released through his Samadhi Sound in the Do You Know Me Now? samadhisound 2003-2014 box set. Once again.

Let’s play a game. Let’s judge the box set from the cover. Or rather, let’s read it.

“It’s a marvellous image. It’s by Ruud Van Empel, a Dutch artist. David is a passionate art collector and he often uses the works of artists he admires inside his own works. The cover image on Manafon was also by Ruud, the deer in the middle of a magnificently green forest. Also here there’s a forest which contains a whole universe. Perfect in representing a recording project where you have to visualize different genres in 10 different albums, which span from ambient to radical experimental music, from spoken word to collaborations with Ryuichi Sakamoto. That forest symbolizes variaty, the trees have some sort of mystery, they are a symbol of beauty, they have marvellous colours. And they raise questions: is it a painting? Is it a drawing? A photo? And to be honest I don’t know it either. And furthermore the lack of any kind of typographical character gives it a sense of mystery, yet lovely. It perfectly represents the sound it contains”.

How did you and David work on it?

“He acts as a real art director. It’s him that chooses the images for the cover, the back cover and the ones inside, everything. Since we’ve been working together, everything runs like that: he brings me different visual elements for the current album and my task is – especially in the case of the box set – to keep everything together in a coherent way, to create the typographical composition, to give a general structure to the tracklist and to the physical support. Furthermore, in this case, I suggested that in order to show the variety of all those albums released in a period of time which goes from 2003 up to 2014, in addition to the original artwork, it would have been necessary to find a greater platform, a book that would describe in detail his work at Samadhi Sound. David found the idea fantastic and he included an interview that fully explains the involved design, as well as a short essay upon that period of his life. Ours has always been more of a collaboration than a relationship between client and maker. In other projects I’m usually the art director, but with David it’s different: he submits material and suggestions, and then I manage design and layout. And we start a long correspondence with ideas, trials, variations. David has a very good eye, he is more than a musician, he’s an artist”.

How does your work influences music?

“My work consits in visualizing sound:

RUMORE N. 381 – page 31

I listen to sounds, melodies, arrangements, and I find the typographical character that represents them, that can express their essence from a visual point of view. Then I think of how a tracklist should look like, if it needs bolds characters in order to express strength, or a smaller size if we want to enhance sweetness. It’s the minutiae, the small details that in my opinion make a packaging a visually strong one. It’s not an easy task. You can create a fantastic cover but if it doesn’t catch the sound and the lyrics’ spirit, it becomes an exercise in style. The secret is to be able to ‘hint’: a mood, an atmosphere, through images and typographical composition. With David this process becomes very easy. With Nine Horses project, for instance, I believe that our collaboration reached one of its peaks. I like the concept, I like the placement of the characters which vertically flow, they work great as if apparently nothing is happening, but in reality there are very delicate touches that reveal many information and fit perfectly to the music”.

How did you meet David Sylvian?

“I was working at 23 Envelope graphic studio, then V23, when a proposal to work on Secrets Of The Beehive arrived. And that was the first time I met him. As a boy I used to listen to Japan, so I knew who he was. I was in awe. But I was also charmed. I chatted a little bit and from that moment on our collaboration has been built step by step. I’m very proud of having been involved in his musical journey. I must say that we haven’t seen each other in person a lot, we mainly speak on the phone or through messages, but I think I can say that we are friends. If he came to London next week I’m sure we would meet for a coffe and a chat. And, similarly, if I were in America, in the city he lives in at the moment, I would for sure pay him a visit to say hello. When we are able to spend some time together it’s always nice. David is a very private person. He’s very thoughtful in everything he does. He has sort of a narrow and tight-knit circle of persons, friends, whom he respects, with whom he interacts and works, but he’s not the type of person that takes you to the restaurant, to a club or things like that”.

What’s the best advice he gave you?

“He always pushes me to do better. He keeps on telling me all the time: ‘Why don’t we try this, why don’t we try that? This is too wary, this is a little bit boring’. Sometimes you need to go beyond your own limits, to overcome your own imagination to find the right idea. And David is very grateful, he appreciates every effort, but then he comes up with a … ‘I apologise for having insisted on other ideas, maybe we should come back to option four’. This continous stimulus towards his collaborators aims to obtain the best from them. And frequently, even if you are dead tired, it’s Friday evening and you’d just like togo back home, on the next Tuesday you usually say to yourself: ‘Well, maybe he was right, he was right to insist.’”

RUMORE N. 381 – page 32

Have you ever disagreed on some choices?

“Sure (laughs), but at the end we always find a common ground. He says: ‘Let me think about it a little while’. He always drags things along, he takes his time… but his are always constructive remarks, accompanied by equally constructive emails. He never tells you that he doesn’t like this thing, or that it doesn’t work full stop, he explains why he doesn’t like that or why it doesn’t work, yet he remains very open. David is amazing. And he also introduced me to artists, as the ones he chooses for the album covers, that otherwise I couldn’t have known”.

How did you find yourself in working on record artwork?

“Before entering the university, I attended the art college. As a child I was always attracted to drawing, you couldn’t say I was a diligent boy, I had troubles with English, with spelling. I was dyslexic. I wasn’t stupid, but at the time I was always at the bottom of the class. Then I discovered drawing. Teachers at school told me that I was good at it and that I should have continued, so I went to the art college. As a child I also loved music, I attended gigs, I’ve always wanted to be part of that world, to work in music industry, to spend time with musicians, to chat with them. And everything actually started from here.”

You are engaged in graphic design and you also teach at Brighton University. In an interview you spoke about the importance for students to learn not to be afraid of failure. How do you balance this aspect with the need of always exploring new and unknown territories?

“Well, I essentially noted that students, when they create something, always think that it should be perfect. This is not necessary true. It’s the wrong attitude. It’s always the case to produce art, to generate moods, to generate atmospheres. It’s difficult to explain, but you have to create and have fun, and you have to try different things, many more than it’s necessary, and you don’t have to just think of the corner where characters must be placed or which colour they must have. You have to explore. Every copywriter collects huge quantities of materials, also Mr. Sylvian must have thrown away thousands of etchings because they didn’t exactly answer to what he wanted to obtain at the time. You have to challenge yourself. I still do it. Because you always want to be surprised, you don’t want to make yourself comfortable, you always want to explore. Students always think that it’s easy… that a computer and an idea are enough”.

Or that Artificial Intelligence is enough…

“Personally I don’t think that it will ever gain any place within creativity. One thing is whether you take a pencil and make a sketch, then you listen to some music and you make another sketch which connects to the previous one; another completely different thing is whether a computer does the same. Everything revolves around computers nowadays, and we are all able to use a computer, but when you want to create a mood I’m not so sure that AI could do it. I heard tracks generated by AI and I found them disquieting. Let’s say that I’m not a fan of it and after all it doesn’t interest me. It’s wonderful to fail, to make mistakes, starting again from there. Best ideas come out of it. Human process, you know, is exciting. However I have a certain age and I started to work before computers, in a totally different world, made of hands, cuttings, glue, so probably I say this just because I don’t know enough. But I’m ready to be proved wrong”.

RUMORE N. 381 – page 33

With regard to mistakes, among your many works, is there any where you still say to yourself that you could have done better?

“Perhaps the last Breeders album I collaborated with, All Nerve. I made many, many experiments with that album, and thinking about it today, five years later, I think that some of the first ones we discarded were more incisive, stronger… Even though, at the end, everytime you look at your own work through time, you think that you could have done better. Instead I’m very proud, for different reasons, of the work I did on Bird Wood Cage, a 1988 album by Wolfgang Press: it’s a strange cover, unusual, maybe unpleasant, but it has something, a certain charm which I always try to find again”.

Give us three reasons for judging an album from its cover.

“The level of involvement. The capacity to make you wonder ‘what does it mean?’, pushing you to want to know more. The ability in representing the music inside. A red cover can not promote a white album. There is nothing worst than buying records that you like, whose cover you can’t look at, and I speak from experience. But when all works, you feel the most beautiful sensation in the world”.

Among your more intriguing pieces of work there’s also one I would define a monumental work. A book of more than 500 pages, Hypergraphia, which ‘illustrates’ David Sylvian lyrics.

“Hypergraphia took us a huge amount of time. It kept on growing. It took four, five years to complete. He was saying ‘let’s add this artist’ or he was bringing photoes he took, he was inserting a short piece here, a little thing there, it was an intense process with also periods of standstill due to my family problems and David’s personal ones. The challenge, at the beginning, was to be able to hold together all David’s career, his love for a set of artists and different interviews, without becoming too heavy. The solution came from splitting up his work in time, on a timeline starting from Japan and arriving to his solo records. It’s an amazing piece of work. When I look at it, even now I can’t believe that it was us that made it”.

It’s a book of poetry and lyrics. Is there one, in all his recordings, that particularly touches you?

“’September is here again’. It’s strange, I just heard September this morning… It’s an extremely simple verse, but sung in a way that calls to mind the exact rhythm of time, the return of September every year, end and beginning at the same time, a circle. It is beautiful as it is. I could tell you a verse in Orpheus or in Let The Happiness In – the problem is that he wrote many wonderful songs – but I state it again: September”.

Do you think that an eclectic artist as David Sylvian could have been more popular?

“I believe that, in a certain sense, he chose his own fate. He makes the records he wants without caring of what other think, and it’s a very beautiful thing. People will always have a personal opinion on his works, somebody will like some of these works, others will like the first ones and others the recent ones, but we must appreciate and respect the sonic and visual journey of an artist, an artist that always tries to surprise himself and that never rests on his laurels. I’m convinced that he could write the most beautiful pop song ever, but what would be the point? He already did it, now he prefers to see how far he can go with his creativity. Whether he becomes popular or not is not a problem, it doesn’t matter”.

In your opinion, why should the world listen more to David Sylvian?

“For the journey. It’s a sonic and visual intriguing journey. And it is endless, no one knows how much music he could still produce and in which direction. I think he’s one of the most interesting artists in the world, he created outstanding works, from pop songs to conceptual tracks, where almost nothing happens, tracks that make you wonder ‘what’s that?’ His secret? No one tells him what to do. He does what he wants and that’s why he has my respect. He’s brave”.

RUMORE N. 381 – page 34

The four seasons of David Sylvian

by Letizia Bognanni and Daniela Liucci

WINTER

What does it mean to grow up in a suburb in Kent, a universe away from London with its Victorian houses, elegant and decadent, all lined up, where albums as The Flight Of The Bumble Bee, South Pacific, The King And I and some Motown classics resound; among tree-lined small roads, a theater, a three century old pub and a mansion, Haddon Hall, where David Bowie, together with his companion at the time, Angie, outlined a first version of Ziggy Stardust? It probably means to develop an early escape desire, magnified by all the art someone can swallow, with an almost atavic hunger and the certainty of having a successful example in one’s own roads. To want to overcome the winter of the mind. The one that the poetess Sylvia Plath described as “scrupulously austere in its order / Of white and black / Ice and rock, each sentiment within border / And heart’s frosty discipline / Exact as a snowflake”.

It’s 1974 when David Alan Batt, his brother Steve and their friend Anthony Michaelides make their own revolution. They dye their hair, invest their money in huge amounts of sophisticated make-up and shoulder their instruments, distilling their own idea of glam rock.

A year after, with two more members (Richard Barbieri and Rob Dean), new names (David Sylvian for David) and a contract with the label Hansa, Japan are born. With a name that winks at Asia, but that actually comes from a brochure left by someone on the bus they took to go to their first live show. Since their early works, Adolescent Sex and Obscure Alternatives (1978), their path is a crossroads of post glam influences, New York Dolls and T. Rex echoes, a yet to be refined art rock, Middle Eastern and Asian influences which don’t have any fear in evolving, in transforming themselves from the primordial chaos of pop ideas to electronic sophistication. Success comes. And the attempt to make them an over-the-counter product for the Far East. Yet David never seems entirely present, his gaze always lost, continuously turned towards an invisible elsewhere. It seems he’s accepting that, yes, things actually work like that; music industry has rules to respect, but he seems more like someone who’s seeking the way to break them.

Japan dragged themselves in a confusion of attempts, style and march changes, as well as in compositions and thoughts. Many are the things that come: electronic and disco, the pressure to wear new romantic uniforms, the usual conflicts between band members, betrayals, David’s attempt to lead to more artsy visions (Quiet Life), a change of label with Gentlemen Take Polaroids. And, above all, the construction of the most beautiful man in the world: androgynous, elegant, elusive, frozen as a porcelain doll. Who is, nevertheless, animated by the fire of waiting for something else. Maybe the results of a meeting, as the one held in occasion of a press conference in Tokyo, with Ryuichi Sakamoto. Maybe the effects of an elegant hit, haughty but at the same time full of drama and oddly prophetic as Ghosts (from Tin Drum, 1982).

“When my chance came to be king/The ghosts of my life blew wilder than the wind”, David sings. Staring to other horizons. Japan are a new, different winter. His winter. The freezing of an already overcome formula. It’s a pop triumph which resembles an ice lolly. Sooner or later it’s bound to melt. To become water again. And when the first ray of sun hits your face and it warms you more than your wollen coat and thick scarf, you know that thaw begins and that you can get going again.

In a interview in “The Face” (October 1982) David explained to journalist Fiona Russell Powell that at the time he was living in a very small flat nearby Gloucester Road, in Kensington, but no, he hadn’t bought it. “I never buy anything. I rent the flat because I feel that if you buy a place, then you’ve actually made a decision to stay somewhere for a long period of time”. Also music, a genre, Japan were probably all short adventures. “It was a disguise, a mask to hide behind”, revealed Sylvian to Sylvie Simmons in 1999 “Mojo” magazine. “It was never an expression of who I was.” The mask was pretty dense in the early days and the whole Japan history can be seen as a survival exercise, a process of departing that concept of art. And of music. “The music was a mask as well. It says nothing about how I was, other than I was hiding, trying desperately to be anything but me”. David Sylvian doesn’t like to be bridled, and the same can be said about his work. “The disadvantage is that you aren’t rooted, and many people need to put down roots in a place to keep their feet on the ground. But that’s not me”.

SPRING

“Writing Ghosts has been a turning point for me. Much of what we created as Japan was built on artifice. With that song I felt I had made a breakthrough, I had touched something true of myself and I had expressed it in a way that it hadn’t made me feel too vulnerable. I knew I had to find my own voice, and I wanted to establish a different relationship with other musicians as well”. In Japan the blossoming season isn’t just an occasion for celebration, but also for reflection on every aspect linked to what a cherry flower symbolizes (sakura), first of all the transience of life. A concept well present in buddhism, which, contrary to Western religions, doesn’t yearn eternity and immortality, but instead embraces the finiteness of things, as it happens for example in traditional mandalas, made by sand and therefore destined to live only through their creation process. So, once the experience with the band has ended, Sylvian starts to discover a different way to conceive music: not a means to reach “eternal life”, in this case fame and popstar status, but to explore the immanent, seconding the flow of changes, inside and outside, creating art for the art itself, and not to feed the Ego, works which are independent from their creator, and which are subject to mutations and rebirths, as all natural processes are.

Following only the flow, the inspiration and the need to find his own voice – his own voices – with the support of his colleague and soulmate Ryuichi Sakamoto (“Ryuichi – he says – was always there in the key moments of my artistic life. It was him who exorcised the angst at the debut of my solo career, encouraging me to realise my first record”), Sylvian makes his solo career blossom on the branches of Brilliant Trees, his debut in 1984, after the dry runs of Bamboo Houses/Bamboo Music and Forbidden Colours. “With Japan I normally had a loose structure to work with, but this was very loose. Musically, there was no major concept, I wanted to create a relaxed environment where musicians could work in so they felt totally at ease to do whatever they liked on the tracks. The whole concept of the album was really to get performances from the people I was addressing, whereas, with Japan, it was never a performance, it was normally an arrangement, a composition. On this album, the compositions are very simple and the idea was to let people work with a very loose structure and improvise over it”.

It is not often that records which mark a clear change of course in the career of an artist receive immediately the right recognition, but Brilliant Trees is one of these cases: “Any who expect David Sylvian’s sheaf of essays to present wafery, neutral music”, Richard Cook was writing on “NME”, “must be confounded by the diversity and strength of Brilliant Trees. This pale young man is fascinating partly through his duplicit position – boychild for the poster popsheets, soulful guru for tenderfoot philosophers – but this crafting of sound is sophisticated and ambitious enough to close down most of this year’s pop”, while Steve Sutherland in “Melody Maker” went one step further: “Brilliant Trees accidentaly reaches the stature Sylvian always looked for. It’s a masterpiece”.

There would have been enough to rest on your laurels, instead David goes on with his search of a perpetual creative Spring, and the following year he publishes Alchemy: An Index Of Possibilities, a completely instrumental work where he explores “subjets and directions which surfaced for the first time during Brilliant Trees sessions”, and then the double album Gone To Earth, where he, more and more plunged in experimentation and in research, allows music to be a reflection of his own spiritual explorations: “Religion is a very important thing for me”, he was saying at the time of the album release, “to discover the What and the Why and to give a positive direction to my life. I want to develop my own spiritual side because I believe that it’s the only important thing in my life. What I’m learning about it, I can’t avoid it to surface in my work. My quest led me to Gurdjieff teachings, to sufism, to gnosticism and to buddhism. All this fascinated me for a certain period. I felt free to explore any interesting path that might cast its spell, and, above all, that might produce some results”.

SUMMER

For an introvert person summer can be the most difficult season, unless someone has got enough confidence in themselves and in their own needs, able to escape social obligations without embarrassment and sense of guilt. Over the course of time, he acquires more and more confidence in his means and working methods and in his artistic personality. David Sylvian, introvert artist as few – also something more, as his brother and collegue Steve Jansen used to say: “Throughout his adult life Dave has shut himself off, with a partner, in quite an isolated situation. He doesn’t partake of the usual pleasures, shall we say. He never did, even when we were touring. Some frontmen can’t stand being at the centre of it all, and have to cultivate a persona even to get on stage. Dave shied away from meeting fans or enjoying being on the road with the band and the crew. He’s ever really gone for a drink in the bar or out on the town. I can’t honestly say why. All I know is that in not doing those things, he gives himself a leverage that he needs” – he learnt how to live his ‘summer’, avoiding social pressure with his innate grace, surrounding himself with kindred spirits, like the bees that title his records.

To the Sylvian’s accurate sound architectures contribute, through the years, Sakamoto, Robert Fripp, Christian Fennesz, Jon Hassell, Holger Czukay, a myriad of musicians met throughout a life spent travelling, where travel isn’t a tour or a holiday but search of sense, a sense that can be found both in ancient places and cultures as Japan, and in the backyard: “Manafon”, he explains in regard to the 2009 album title, “is a village in Wales, a village in which poet R. S. Thomas lived for sometime and served as rector to the parish. In this small village Thomas had trouble filling the pews of a Sunday but in a sense it was something of an idyllic spot in which to raise a child […], master his profession and write his poetry. So the physically real village became for me a metaphor for the poetic imagination”.

Real or imaginery journeys and meetings nourish the imagination of Sylvian, who’s not a misanthrope or a reclusive thinker but an intelligence that absorbs energy from what he sees, listens, reads, pouring all of this into music. So in his songs, filtered by his personal experience, there are references to writers, philosophers, directors, from Nightporter by Liliana Cavani to Joan Didion’s autobiography, from classical myths (Orpheus) to Milan Kundera’s The Book of Laughter And Forgetting: “Basically it happens that you absorb a lot of information and all of a sudden you find them surfacing in the composition. I tend to use a lot of titles coming from other media such as cinema or literature. It’s a personal reference to something. It means that something in that movie, in that book or in anything else, has contributed to bring out the nature of a certain musical piece. But it never exclusively originates from a movie or a book. Never, never. It comes from personal experience. But something in the movie, or in the book, has contributed to move the needle of the scale and it has helped things to flow”. As nectar to a bee, an animal that in many cultures symbolizes abundance and renewal of life, eloquence and intelligence, in Greek mithology it’s the Muses’ messenger, in Hindu tradition it’s linked to Om, the universe primordial sound.

AUTOMN

“Mr. Sylvian is a Mark Rothko. Inside him there’s an extreme wealth in terms of creativity. It’s a collection of many elements. Like a Rohtko’s painting, with its wonderful, subtle and lovely colour combinations, starting from red and yellow for then finding orange shades, or sometimes those darker colours as browns, which at times get even darker up to the point of setting free the shades of blue and black”.

David Sylvian’s secret, as graphic artist and one of his most active collaborators, Chris Bigg, would say, is in character. The typographical one. But also the one inside the artist: a river in flood whose only interest is to flow. A tree goes through seasons without fearing time and terrains. An automn, an apparently rarefied season, where monotony and suspension seem to rule, prelude to the winter of the mind and body, which instead is an explosion of colours and nuances. The same ones that David Sylvian chooses to test what’s abstract. He already tasted, chewed and rejected pop and popularity. As an indigestible bite. He chooses to go further, to enter and go deep into the unknown, opting for creating meanings between the lines, pouring on the listener his long inward-looking excursions, capturing him/her to the rhythm of a constant change. Latest explored territories are the ones called by the most “the less accessible” or, using a more appealing word, “avant-guarde”. Winding paths that help to appease the hunger and thirst of knowledge, enlightenment, creation.

Sylvian’s Automn is pure experimentation. It’s penetrating universes and dimensions which blend jazz with poetry, visual art and digitalization, electronic and ambient textures, improvisation and “daily” soundtrack play, flirting with atonality and exchanging visions with artists such as Derek Bailey, Christian Fennesz, John Tilbury or Sachiko M, without a map, trying infinite combinations to know what it’s like, shaping signifiers and significances. From Blemish to Snow Borne Sorrow (a 2005 collaboration with Japan ex members, under Nine Horses moniker) soundscapes multiply, splitting and overlapping. They fluctuate from neo noir darkness to glitch light, they talk about breakups and catharsis, they feed on minimalism and silences (Manafon, 2009), they become unpredictable, mysterious, cryptic, moulding themselves into their creator, who’s always out of sight, almost dematerialized, at the point of not performing live anymore and collaborating with the artists he loves via file exchange.

“Since the early 80s I’ve been interested in deconstructing the familiar forms of popular song, in retaining the structure but removing the pillars of support”, he explains to Keith Rowe in 2015 “Bomb Magazine” interview. “My work continually returns to this question: how much of the framework can you remove while still being able to identify what is, after all, a familiar form?”. The answer, the answers, have fallen as October leaves, piece by piece, forming a variegated carpet full of colours.

Under the auspices of Samadhi Sound, the label he established right in early Zero years to officialise his emancipation from music industry, he has refined his manifesto. Which proudly goes against the grain. But not as a cliché, instead as an expansion of the concept of music to sound art. Without having to give any explanation. Same as when Rothko, together with his colleague Adolph Gottlieb, wrote in a letter to “New York Times” on June 13th 1943: “We are not going to defend our works. They stand up for themselves. We consider them precise statements […] our art is an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by the ones that are ready to take the risk”. And with David Sylvian taking the risk is never a mistake. He won’t ever force anyone to do it, but those who do so will be enriched. In points of view. Thoughts. Humanity. Someone wondered if his career would be more interesting and full of appeal if he had followed the opposite course. If the initial experimentation had led to the popolarity of Japan. Here too there are no answers. Just one consideration: with David Sylvian everything is a possibility. Like the seasons that return without ever bringing a déjà-vu for its own sake. Like an automn that, year after year, even in its cyclicality, always knows how to unveil new, exciting shades.

Trasnlations of the side columns, translated by Marta Roia.

RUMORE N. 381 – page 32

DAVID SYLVIAN – 3 TIPS

Polaroid from the beehive

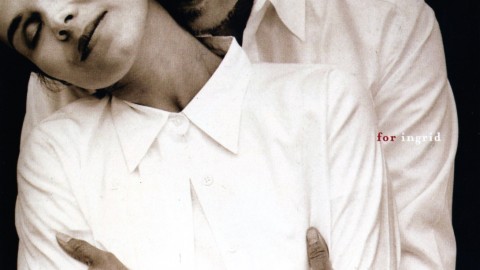

Among the many roles Ryuichi Sakamoto played in David Sylvian’s life there’s also the one of Cupid: the meeting with Ingrid Chavez, who will become his wife, happens while the two are collaborating in Heartbeat by Sakamoto.

When David Sylvian was on the verge of abandoning music at the end of the 90s, due to the troubles he was having in completing Dead Bees On A Cake, his spiritual advisors convinced him not to retreat.

Among David Sylvian’s projetcs, there’s one that remained unreleased, except for surprises: it’s the collaboration with Joan As Police Woman, announced by Joan Wasser in 2011 and then in 2014.

RUMORE N. 381 – page 33

DAVID SYLVIAN

DO YOU KNOW ME NOW?

SAMADHISOUND 2003-2014

SAMADHI SOUND/UNIVERSAL

79/100

If you think you knew me then, do you know me now? In the case of a peculiar artist as David Sylvian, more than the questions and the answers, what counts are the stories. And more precisely, History, with capital letter, the one of a journey started with two choices: to unburden himself of the limiting label of popstar in a band of popstars; and to free himself, at the new millennium dawn, from the obligations and pressing impositions by a major, in the attempt to give a precise direction to a solo career that wants to pursue infinite paths. At the same time, Do You Know Me Now?, 10 CDs that cover Sylvian’s production from 2003 up to 2014, is the snap-shot of an independence statement, still valid today, born between the ‘walls’ of Samadhi Sound, his own label. A revolution that bursts into the improvisations and cathartic turmoil of Blemish, a record that marks the end of many things, including the marriage with the American artist Ingrid Chavez, and that record after record – with a 1000 page book, marvelously edited together with his faithful Chris Bigg – leads to Manafon’s abstract electronic music, to the 70 hypnotic minutes, between ambient and musique concrète, of the installation piece named When Loud Weather Buffeted Naoshima, to the more linear poetry distilled with Franz Wright and Christian Fennesz in There’s A Light That Enters Houses When No Other House Is In Sight; to the experiments with Nine Horses (Snow Borne Sorrow; Do You Know Me Now?, with Ryuichi Sakamoto contribution) or with Jan Bang and Erik Honoré (Uncommon Deities). In his uninterrupted extending, demolishing, recomposing and lessening popular music borders. Just asking to leave expectations at home, to open the mind and to completely plunge in sound. Just asking to trust him, because – you can be certain – you’ll be rewarded.

Daniela Liucci

Many thanks to Marta Roia for the friendly offering- and making of the translation of these magazine articles.