by Anil Prasad (innerviews.org)

Interview by Anil Prasad who is the owner and maintainer of the excellent music site Innerviews. Interview date: April 19th 1999

It is as it should be.

Those words are spoken by singer-songwriter David Sylvian in a new promotional film called Time Spent. The short describes the motivations and methods behind his new album Dead Bees On A Cake. Borne of his ever-deepening involvement with Eastern religions, it’s a simple statement with incredibly complex underpinnings. And after spending time in his company, it becomes clear that he wishes the explanation was enough to satisfy the throngs of media types and fans perpetually seeking commentary on his work.

When speaking to Innerviews, Sylvian immediately conveyed his dissatisfaction with the media process. It’s a disquieting perspective for a journalist to encounter at point blank range. But when one considers that he essentially grew up in a public spotlight surrounded with bagfuls of dirty laundry, the outlook is understandable.

Much to his chagrin, Sylvian is still most identified as the lead singer and key muse of the British avant-glam act Japan. The quartet also featured Mick Karn on bass, Richard Barbieri on keyboards and his brother Steve Jansen on drums. Formed in the late ’70s, the group was responsible for some distinctly eclectic pop that stood far above the rest of what was lumped into the so-called “new romantic movement.” Its 1982 Tin Drum album remains a high water mark of the era. Unfortunately, the band’s image betrayed its music. Such is the cumulative effect of years spent wearing caked-on make-up and architecturally-engineered hairstyles.

Japan broke up shortly after Tin Drum. Awash in acrimony, hurt feelings and howling accusations, it was a messy split with wounds that remain to this day. Sylvian says he left because he needed to find his own voice. The rest of the band spun it differently. “The David Sylvian we’d always known was one of complete control. And that made it very difficult for us to work with him,” Karn told Innerviews.

Sylvian wasted no time establishing a solo career. Mid-1983 saw the release of his debut Brilliant Trees. The uneven disc occupied a middle ground between overtly commercial pop and a genuine desire to head into more cerebral and experimental territory. It also saw the falsetto vocals of his Japan years evolving into the deep, aural charcoal that is his natural range.

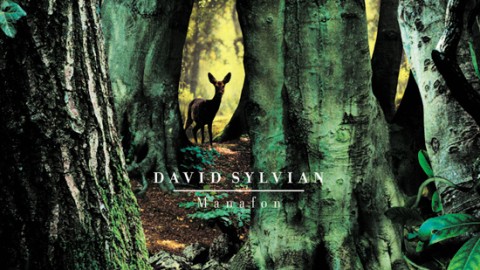

Sylvian’s musical journey since Brilliant Trees is a remarkable one. It’s resulted in several stunning albums such as 1985’s Gone To Earth and 1987’s Secrets Of The Beehive. Full of flickering atmospheres, subtle orchestration and intensely moving imagery and metaphors, they revealed an artist at the height of his creative powers. The discs also showcased Sylvian’s prowess in choosing sidemen. Daring, eclectic virtuosos including keyboardist/arranger Ryuichi Sakamoto, guitarists David Torn and Bill Nelson, and bassists Danny Thompson and Holger Czukay are just a few of the exceptional musicians gracing the albums.

The next step in Sylvian’s career was an unexpected one. In 1989, he once again found himself working with Jansen, Karn and Barbieri. Collectively, the group decided that the passage of time, the emergence of individual artistic personas and deepened maturity could lend itself to new and innovative musical possibilities. Much to the surprise, annoyance and frustration of the music industry, media and fans, the resulting album did not emerge under the name Japan. Instead, the moniker Rain Tree Crow was employed for the self-titled effort. It made sense though. Other than the names of the participants, Rain Tree Crow’s moody soundscapes hardly bear any resemblance to Japan. Perhaps inevitably, the reunion was short-lived. Many of the same forces that conspired to dissolve Japan once again reared their ugly heads and the four went their separate ways.

Rain Tree Crow wasn’t Sylvian’s only post-Japan collaborative effort. He’s released four duo albums to date. He explored the world of ambient music with Czukay on 1988’s Plight and Premonition and 1989’s Flux and Mutability. And the somewhat unbecoming world of crunchy, testosterone-laced rock was at the core of 1993’s The First Day and 1994’s Damage with guitarist Robert Fripp.

Sylvian looks back at the Fripp collaborations with very mixed feelings. But he considers the accompanying tour a triumph in that it boosted his confidence as a performerso much so that the increasingly reclusive musician launched a solo tour in 1995 called Slowfire. During those gigs, his songs were stripped of any ornamentation and performed with only acoustic guitar or keyboards. Clearly, the notion of simplicity struck a major chord as the just-released Dead Bees On A Cake is his most direct and personal piece of work to date.

Five years in the making, Dead Bees explores the hazy intersection between corporeal existence and spirituality. At its basis is a pilgrimage into the worlds of Hinduism and Buddhism. Go up a layer and one encounters an awakening to the importance and meaning of familya realm he’s intimately connected with since his 1992 marriage to poet and singer Ingrid Chavez. Dead Bees is truly a period album. It’s unlikely that Sylvian, now 41 and the father of three, could have explored these themes with such nuance and depth previouslysuch is the impact of his recent personal, spiritual and artistic growth.

Musically, the album continues in Sylvian’s tradition of working with some of the finest musicians available. Guitarists Marc Ribot and Bill Frisell, tabla renaissance man Talvin Singh and trumpet master Kenny Wheeler all contribute. But unlike his previous releases, their work is placed in a more straightforwardalmost reservedcontext. With few exceptions, Dead Bees’ soothing pop and R&B-flavored pieces favor complex thoughts and moods, not arrangements.

Creating Dead Bees was a deeply frustrating task for Sylvian. It involved several false starts, constant rethought and collaborations and guest contributions that didn’t work to his liking. Surprisingly, his long-term working relationship with Ryuichi Sakamoto was one of them. Sylvian first started working on the disc at Sakamoto’s New York studio. But once he realized their normally fruitful synergy had gone awry, he moved on to Peter Gabriel’s famed Real World Studios in Britain to continue. Then the recording budget ran out. He ended up finishing the album in isolation at his home studio in Napa, California.

As Sylvian says in Time Spent, “We are not given more than we can handle.” And while he certainly handled a lot making Dead Bees, the end result is closer to his heart than any other project he’s been involved with. But will listeners understand the path that led to the album? Do they need to? Innerviews began its very revealing and rewarding conversation with Sylvian by exploring this topic.

The new album possesses a very personal and spiritual flavor. But if listeners aren’t paying attention to the peripheral media information generated, they might not grasp the deep meaning embedded in it. Does that potential loss of intent concern you?

I’m not interested in the listener coming to the work and viewing it as a snippet of autobiography. What’s important to me is that people come to the work and in some ways open up to it so it can become relevant to their lives in some way. There’s a substance to the work, but people needn’t know the background to the work in terms of my motivation and the main themes running throughout. They can work those out for themselves in whatever way they choose to approach it. It’s not crucial that this is relayed in the media in any way other than it can possibly draw people’s interest to the work that might otherwise pass it by.

On several occasions, you’ve said that your interaction with the media results in half-truths at best. How is what you say through the record more honest and truthful?

To describe the work or pin it down in any way is only to take a stab at it. Ultimately, the essence of the work goes beyond my understanding of it. A piece of work has an inner life and that goes beyond the creator’s experience of the work in that I’m very much aware that the music comes through me and not from me. I give the work form and maybe dress it up in something of an autobiographical nature because that’s how I respond to the emotional content of the workI can only dress it up in my own experience. That’s how I approach the work, but nevertheless, there’s something much greater than that at the essence of the work should you desire to delve into it that far. So, for me to pin it down in languagein terms of speaking about itis not to do it justice.

You’ve described your material as deriving from love, devotion and divine intoxication. You steer clear of more base expression such as sarcasm, hatred or revulsion. How do you deflect those instincts when writing?

I don’t really enter into that space when I’m working. Sometimes in my work there can be an underlying sense of anger, frustration or anxiety, but there’s no room for sarcasm. There’s very little room in my work for irony too. I’m looking for something that has a greater clarity than that. I hope the work reflects an emotional complexity, because for me it’s important that the listener comes to the work and finds themselves in the work regardless of the state of the mind they approach the work in. In other words, if I say the album is celebratory in feel, I still believe it’s important to reflect the more shadowy aspects of human nature as well as the positive aspects to paint a full picture. I believe we don’t experience one pure emotion. Its opposite is always present and it’s surrounded by a whole complexity of emotions. For a piece of work to be true, it has to reflect that complexity. The stronger the work, the more complex it is emotionally. It can embrace all emotion.

I don’t know how to define sarcasm, but that wouldn’t necessarily be part of that emotional complexity that we’re talking about because that would stem from another source. To be sarcastic would be to have negative feelings that are more deep-rooted. If we get down to the root, we may find hatred or fear or any of the more base emotions. I think there’s room for all of that in musicthere’s room for expression of fear. But hatred? I tend to steer clear of that, but it’s not something I do on an entirely conscious level. It’s not something I feel on a very powerful level, so it doesn’t come through in the work to a large degree, if it comes across at all.

You possess an open-ended approach to spirituality that draws primarily from Hinduism and other Eastern religions. Why are you still so drawn to Christian imagery such as heaven and hell?

Um, yes, that’s funny isn’t it? It’s entirely to do with upbringing. And often I haven’t been aware of it until after the composition is complete. I know there were greater references to heaven and hell and devils and angels on Beehive than on later work. I found that quite peculiar also, but I think it’s entirely to do with background and it surfaced in the work quite naturally. I think it is less apparent now than it was. But they are metaphors that can be used and aren’t redundant in any way, regardless of the disciplines that embrace my life currently.

Describe your upbringing from a religious perspective.

There wasn’t a heavy religious influence in my upbringing. I was brought up in a Christian environment and I mean that in the loosest terms possible. In England, during the period I was brought up in, we’d be singing Christian hymns in the schools. We’d be doing our scripture lessons in which we’d study the bible. It wasn’t a Christian school per se. It was part of the national curriculum. It was thrown out of the curriculum some years later after I left school. So, I was brought up with that kind of imagery and we’re all indoctrinated with that to some degree. It was something we had to go through regardless of our own religious space and beliefs.

That typical British Christian upbringing can encourage a great deal of fear and guilt. Did your move into Eastern spiritual disciplines free you from a lot of that?

I think it did. There came a point relatively late in life around ’81 to ’83 where I began to question just about every aspect of my life. My beliefs, such as they were, came in for closer scrutiny. I had a great sense of doubt in the kind of religious upbringing I had been given and the sort of childlike faith I had. The pull of Buddhism appealed to me because of the clarity of itparticularly Zen Buddhism. What ultimately appealed to me is that it is a discipline where belief isn’t necessary. You follow a systematic set of rules in a sense. It had a clarity that allowed me to embrace a discipline without necessarily embracing a doctrine per se. So, later on in life, I was able to come to Hinduism and embrace aspects of that culture because I had been through a period of Buddhist studies that freed me up from the dogma of Christianity that I had grown up with. I was able to come back to a more devotional approach to my spiritual disciplines that didn’t have that implied dogma. That was liberating because it wasn’t in my backgroundmy personal upbringing.

Your spiritual teachers are some of the most important people in your life. Have you considered that there are those who consider you a teacher? In an age bereft of genuine spiritual connections, one could postulate that lyrics are the closest equivalent to sacred text many encounter.

The music itself has an inner life and anything that comes through to the listener that is life-enhancing doesn’t belong to me. That’s the core essence of the work that’s having its effect on the listener. I’m just the conduit, so therefore if people see me as a teacher of any kind, I’m not sure that’s appropriate. I’m just one of the people that are pointing to the way just by pursuing a personal patha possible path. But I don’t suggest for one instance that people take notice of the path I choose to take or have any interest in the aspects of religion and spirituality that I do. It’s not appropriate for me to be dogmatic about my own beliefs in any way. It’s just that people have an interest in the work and they want to know what informs it. So, I speak about it and that’s my only reason for doing so.

Let’s discuss your collaborative approach. A colleague of yours implied that you almost systematically alienate some of your collaborators whether you’re conscious of it or not. This person wasn’t criticizing you, but suggesting that this is simply a part of your creative processa means to an end. Do you consider this a valid perspective?

[long pause] I don’t know. I see it happening, so I can’t deny that it happens, but it doesn’t happen in all instances. There are many strange occurrences that I have no explanation for in terms of personal relationships in the collaborative framework. There’s been clear instances where one person in a group collaboration will utter something to one of the musicians involved and get no response. And if I say exactly the same thing or reiterate what that person’s just said, I’ll get a hostile reaction. [laughs] It’s never been clear why. It must be something to do with the way I express or project myself and it baffles me sometimes. So, people do respond to me in different ways and I’m as interested as anybody else in why I get certain responses out of people. It’s not always negative obviously, but occasionally it can be. I may alienate the people, but not necessarily through the specifics of what I’m saying, but maybe because of how I express it or how the people view me. When they hear the same words coming from me as opposed to someone else, how they view me influences how they hear what I’m saying. I really don’t know. This is a difficult one for me to get to grips with.

What’s an example of a phrase you might use that could be viewed positively or negatively depending on a musician’s view of you?

That would be difficult to pin down. It could be just giving somebody direction with no criticism inherent in what I’m actually sayingjust giving clear direction. One person will take it as a positive guide and then another might take it as an affront to their own creativity. I can’t be more specific than that, but the times that this has happened to me are numerous. It may have more to with personal relationships than anything else.

My understanding is that you don’t have any formal music training. Given that, how do you go about directing some of the virtuoso musicians employed on your albums?

I suppose I should say that with the majority of people I collaborate with, there is a mutual respect of some kind established. There is very rarely a problem involved with the creating of music. I think I can call up just about every collaborator I’ve worked with in the past 15 years and get a positive response to the call to come work. None of the relationships are damaged in that respect, with the possible exception of the members of the Rain Tree Crow set-up. Having said that, when I’m arranging a piece of music, it’s the composition or the arrangement itself that is crying out for a certain voice. That voice is that within my own frame of reference. I’m making a connection between a body of work and a particular piece I’m working on. So, it’s a matter of inviting a musician in to see if they can also make that connection. More often than not, there is a need for a dialogue of some kind to establish the common ground. The common ground already exists in my mind and I’m hoping that that the musician coming in to work with me can recognize that. I have to say that nine times out of 10 it works extremely wellthere isn’t whole lot of need for dialogue.

I tend to have more problems with contributions that aren’t as major as the major collaborations I’ve had that people point to. It tends to be on a much smaller leveldealing with performance on one level or another such as the timing of a drummer’s performance, the pattern played on a bass guitar and other very minor details. That’s why I tend to butt heads with some of the musicians I work with, but never to the degree that there is a major difficulty. If I recognize that I’m pushing a musician into working in a way that they feel uncomfortable with, I just call an end to the session and there is no animosity in that. Sometimes, there’s a certain amount of discomfortthey recognize that I’m unhappy with the work. Ultimately, it’s better that it end that way than take it a step further and push them into performing a piece in a way that they feel is uncomfortable and unnatural to them, and where I’m not getting the work that I want because I’m not really getting the performance I need. Rather, I’m getting somebody that in some way is resisting the work and I can’t work with that.

Speaking of Rain Tree Crow, I’d like to relay something Mick Karn told Innerviews. He said “I do think that tension, as unbearable as it may be, does produce something that is stronger than the individual parts. I do think that when the four of us are together, there is something unique produced, and I’d like to see that happen again. I think Rain Tree Crow was a huge step away from the sound of Japan, and I’m really curious to see what the next step would be if we did get together.” What’s your reaction to that?

[long pause] I agree with what he’s saying. I agree with the fact that there is something unique when the four of us enter into a musical relationship with one anothersomething unique comes out of that. My reason for believing that is we grew up with one another musically and that means we have this common vocabulary which is very rare. You rarely find it in a group of musicians unless it’s an established group that’s been working together for a long period of time. Now, as a solo artist, it’s very difficult for me to reestablish that level of communication with musicians that I only have relative familiarity with. I have a good grounding with Ryuichi [Sakamoto] which is why I constantly work with him. We share a common vocabulary that allows us to quickly establish a groundwork and move further and further afield when we’re writing and arranging pieces together. That’s wonderful because there’s nothing worse than getting bogged down trying to establish that common ground with a musician because you know that the performance isn’t going to stretch beyond those boundaries because there isn’t that mutual understanding. So, when I’m working with a group of musicians like the Rain Tree Crow band, we have that common ground already established and therefore it’s a matter of shooting off from there in all different directions and there’s a wonderful sense of freedom in that and a shared common goal if you like. I have yet to reestablish that in life except with a few individual musicians. I haven’t found it within a group of musicians in a way that I have with those boys. So, yes, when we get together in a room something special will happen.

Will it happen again? Do I desire that it happen again? [very long pause] What happened at the break-up of the Rain Tree Crow project and all the animosity that surfaced as a result of external pressuresI view it as being terribly unfortunate. It means a trust was broken between myself and the other members of the band, although it has been reestablished to some degree with my brother againas I knew it would be. To allow a musical relationship to truly flourish in the way that it did on the Rain Tree Crow project, there has to be a high level of trust. Mick placed a high level of trust in me as I was primarily producing the album. He gave me enormous freedom when asking him to adapt this or that style of playing or whatever he was doing. Would he have the same amount of trust in me now? I don’t know. And it’s not because of anything musically that’s happened. It’s because so much has been said. A lot of it has come from Mick himself. Can it be reestablished? Can he open himself up to that level of trust again? I don’t know that he can. So, that makes me question the reasons why we would be getting back together again. I’m not sure we can ever set that up quite the same as it was during the Rain Tree Crow project. Had the recording of the Rain Tree Crow album been completed without any animosity, with a great level of excitement, enthusiasm, love and good humorthat’s the true relation of the band prior to external influences coming into playwe were talking about doing a second and third project, and a tour. I think that would have been absolutely wonderful. It didn’t happen and I’m not sure we can ever reestablish that trust again, but I try to remain open-minded to it.

Are you surprised by what Karn said?

Not really, because we’ve known each other for so many years. It’s family. You can have these big battles. [laughs] Yet, you still remain family to some degree. We just have to see how things unfold in the future. It’s certainly not something I’m thinking right now and I’m sure Mick doesn’t dwell on it. It’s just when asked, it’s a matter of remaining open to the possibilities as they arise, but I don’t think it’s going to happen anytime soonif at all.

Time Spent, the promotional film that accompanied the release of Dead Bees On a Cake, contains some very personal thoughts and private footage of you and your family. What was your motivation for creating it?

Virgin were doing the rounds and asking different directors if they were interested in doing the project, and as always there’s a terribly low budget and restrictions. If they’re going to earn any money, they have to keep things pretty simplistic. [laughs] And Ingrid and I thought “Well, we’ll just buy a camera with the budget and put something together ourselves.” And basically, that’s all we did. I wanted to do something that was based on the family and our life together, purely because this album was born out of that environment. To focus on anything else would be untrue. Basically, it’d be trying to conceal for the sake of privacy. As much as I value my privacy, I thought it wouldn’t hurt to open the doors a little because we’d be in control of the material. So, it alludes to some aspects of our lives togetherour family as it’s presented, the spiritual life a degree that it’s touch upon, and some basic philosophical guidelines that underlie our life as it’s lived together.

You now reside in America, a country with a gift for homogenizing culture down to the lowest common denominator. I imagine you provide your children with some specific ideas about art and expression to counter that influence.

That’s something that evolves over time for me in terms of my relationship to my childrenwhatever they’re able to take onboard at any point in time and however their interests develop over time. We have a 14-year-old boy that has a wonderful gift for visual arthe’s a painter and a sculptor. So, we try to help him focus on that creative aspect of his own being above any other interests that he might have. At the same time, he’s his own person. He has other interests and of course at that age they’re numerous and a lot of them don’t involve making the most of his abilities necessarily. But it’s a matter of making him focus to the best of his ability without enforcing a strict discipline of any kind, unless he’s open to it or unless he wants to embrace it for his own good. And we’ve encouraged that. I’ve known him since he was sevenhe’s Ingrid’s boyand at that age he was very much into the video games and all of that. His ability to draw and paint was undermined by the amount of time he would waste on other things such as the video games and it influenced his vocabulary and the drawingsthe few that he did do. At that point, we got involved with very spiritual teachers and at one point we spoke about the fact that his art was being undermined by his interest in other aspects of entertainment and all the rest of it. At a certain point, he decided to put all of that aside and to focus on his work again. That was partly our influence and partly the influence of the environment he found himself in when travelling with certain spiritual teachers. He’s brought into that environment because his parents have an interest in it.

The two girls are much younger. They take it for granted that they are surrounded by people that have a spiritual belief of one kind or another that lead a devotional life. It’s so much a part of their life that they don’t question it. But to our boy, he had to learn how to understand itto embrace it. It was kind of odd to him at first to witness this. Then he slowly opened up to italthough nothing’s been imposed upon him. I think soaking in that kind of influence just through sharing the company of his parents has a positive effect on him. But he keeps a very good balance between what we introduce him to and what his social circles introduce him to. At the age of 14, he has a greater understanding of the importance of time and how it is spent and what the priorities are and that he should focus on them. It is something he’s grown into over a period of time with a certain amount of influence from us, but ultimately, he’s his own person. He has to make up his own mind on how to focus his life and make use of it. We take the same approach with our younger children. Obviously, at these agesfive and seventeen monthsthey’re soaking up the life their parents lead. They’re very influenced by it to one degree or another, but it’s hard to see how that’s going to play out right now. All we try and do is to introduce certain ideas if you likethe notion of devotion, of worship, a quiet mind, a quiet heartjust ideas that we can speak about or represent in our daily lives together.

Why do you consider America an ideal place to raise your family?

Ideal is a strong word. I don’t think of it in those terms. It’s where we find ourselves. Do we conceive of another place being more appropriate than where we are now? Not really. It seems to me we found ourselves in California through wanting to be closer to particular teachers in our lives. We have access to those teachers where we’re currently living. It helps Ingrid and I focus and stay focused which can only be a benefit to the children. Basically, we could live anywhere in the world. The problem is: can we sustain our focus and interest in our discipline? We think this is the most important, underlying aspect of our lives and if we lose sight of that, who knows where we’ll be led? We want to develop further this aspect of our lives and to do that, we need to be near a teacher to both inspire the practice itself, to inspire lives of devotionincreasing levels of devotionbecause of the world we live in and the kinds of activities we’re involved in that take us away from that so often. We need a good grounding and assistance in focusing. I know what it’s like to be without a teacher and without that focusto work entirely alone with certain disciplines and ultimately the practice dies out because there isn’t enough to sustain it.

Your guitar skills have evolved significantly over the last ten years. Assess the distance traveled.

As a guitarist? Hmm. Well, guitar was always my first instrument and I’ve never been particularly proficient at any instrument. [laughs] I still don’t consider that I am. It’s a constant evolution. I think at one certain point, probably around the time of Gone to Earth, I started making guitar loops and wanted to explore those kinds of ambient qualities with guitar above any other instrument. I sort of delved into it a little bit further to make the most of my limitations by using a variety of different technologies. I think through that period and following from Beehive, I spent a lot of time playing with guitars and playing with effects and processors of one kind or another. And at that time, I picked up a Steinberger guitar. That opened up the possibilities to a larger extent at that point in time. I think the guitar became more and more of a focus after Beehive for me. In terms of being in the Rain Tree Crow set-up, I enjoyed being a guitarist for that group. I mean, I really enjoyed playing guitar at that point in time. I was really enjoying immersing myself in it. Now, I’ve reached a level of proficiency that allows me to perform solos and vocal accompaniment and so forth. I still turn to other playersmore proficient playersfor different kinds of performances and different levels of performances. But if I can cover a base with my own playing, I do, just because even for all its lack of complexity, I can pinpoint the emotion that I’m looking for. I know precisely what it is I can find it in my own playing and nail it more succinctly than a third party.

What was it like for you to perform solo during the Slowfire tour with just an acoustic guitar?

It was quite a daunting prospect to be honest. I don’t think I could have taken on that tour at any other point other than that moment of time. There are a number of reasons for that. For instance, the pleasures of performing live revealed to me through working with Robert Fripp. I think the primary experience taken from that collaboration was the pleasure of performing live. And at the same time, I had come into contact with teachers we spoke of, and I saw the possibilities of doing a solo tour as something of a discipline. It’s kind of presumptuous of a non-musician to take the stage alone and ask the audience to be engaged. But I had an increased level confidence in my role as a vocalist, so that helped me somewhat. I felt a little more comfortable onstage due to working with Robert, and I had a spiritual discipline with which to focus my mind on the workto sit center-stage and perform wholeheartedly. By viewing it in that light, I was able to undertake the tour and found it to be enormously rewarding as a result.

You’ve been vaguely critical of The First Day and Damage recently. What do you find dissatisfying about those albums?

I wasn’t overly dissatisfied with The First Day. There are certain albums that maybe aren’t entirely necessary, you know? The second album I did with Holger Czukay and maybe the albums with Robert are the ones that aren’t entirely necessary from the public’s perspective. From my perspective they were necessary.

Can you elaborate on that?

Well, the experience of making The First Day was necessary. I benefited from the experience enormously, although it was a very difficult album to make. Robert and I had our own private crises that we were going through at that point in time. Robert was wrapped up with E’G and all that was going on there with lawsuits and all the rest of it. I had just left the shores of the U.K. after waiting six months to get into the States. I was at home for two weeks with my family prior to being thrown into this project and I just wasn’t prepared for it. I wasn’t mentally ready to get involved in recording an album with Robert. I don’t think Robert was all there either. But at the same time, there was a lot to be expressed. I had been through a periodhow can I put it? It was a long period of disquiet reallyan experience that had been debilitating for a number of years and I was finally emerging from it. I found that Robert had created a wonderful context for me to express the rather negative feelings that I had during that period of timethe anger, the frustration, the anxiety I felt.

Are you comfortable describing what that negative situation was?

Um, it’s difficult for me to get into without it getting very personal. I was surfacing from the experience and there was also a resolution to it. It wasn’t a purely negative experience. It was cathartic. So, not only was the expression of this material a cathartic process for me, the act of creating the work in the studio was somewhat cathartic. It was riddled with difficulties of one kind or another. Robert and I have very different methods of working. Robert is very much of the old school process of basically capturing a performance live and that’s so far removed from what I’m looking for nine times out of 10. We didn’t actually work that closely in the studio. Robert would come in the morning and do a series of performances and I would spend the remainder of the day either editing his performances or working on something of my own. Robert would then come in at the end of the day and say “What do we have?” I didn’t help select the musicians. It was a context of Robert’s making which was unusual for me. We weren’t close-knit in terms of the creation of the music, so ultimately, as I say, the album was cathartic for both of us in many ways at that moment of time. There was a lot of to be expressed and I truly appreciate how it helped me work through certain experiences, but I don’t feel particularly close to the material at this point in time. Maybe that’s necessary with something that allows this sort of recovery or renewal to take placeyou don’t want to go back and dwell on that material.

I know you cherish your solitude and try to stay as far away from conventional, mass-mediated existence as possible. Why is seclusion of such value to you?

[long pause] I guess I need that solitude to focus on the work that I do as much as anything else. I like to create in isolation. The notion that there is a whole industry out there waiting for another album to be released at this or that moment in time can only be a hindrance to me. I need to isolate myself to such a point where none of that will come into play when I’m working. And it never does. That’s purely because of the way I’ve set things up for myselfmy immediate environment and all the rest of it. I know how to get the best results from my work given the right environment to work. I try to create the ultimate set-up that allows me to work with freedom of heart and mind and focus. I think that talking like this on a daily basis, which I’ve been doing for a period of months now, begins to eat away at me. It’s particularly when I realize that I’m repeating myselfnot in what we’re talking about today, mercifully. A lot of what I say is constantly repeating, repeating, repeating, repeating and I find myself in a rather distraught frame of mind. It’s one that is certainly not creative. This unnatural repetition becomes a story that I am relating or relaying and not something that I’m expressing as something of myself because I’m on automatic pilot. It’s strange to be recounting things that have happened to you personally that mean a lot in such a rather automatic manner. You feel removed from your life to some degree because you’ve told the story so many times. You become numb to your own existence which is really strange. There comes a point where I have to turn all of that off just so that I can feel and relate to my own life on whatever level is necessary for me to allow new work to come about. That’s why I keep that distance.